by Stephen Rohde, published on Socialist Action*, April 8, 2023

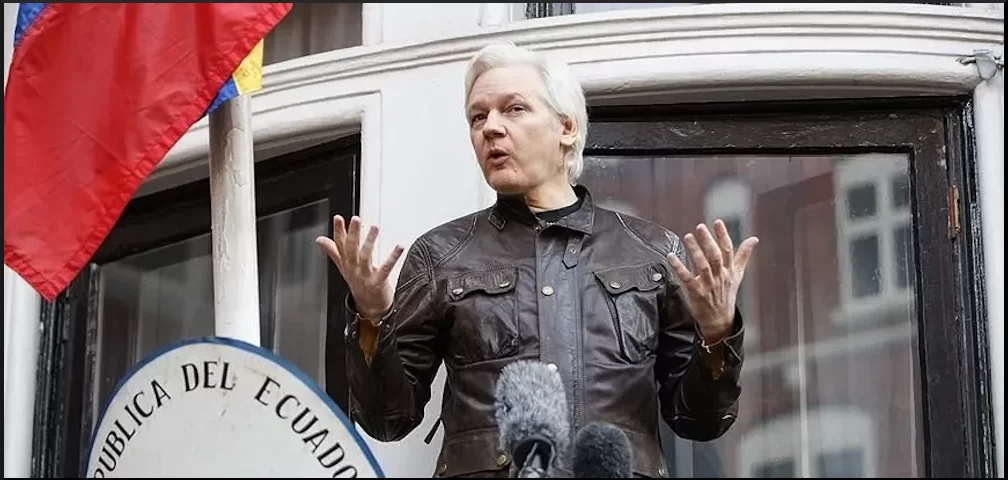

Like the Trump administration that preceded it, the Biden administration is seeking the extradition of WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange to stand trial on an indictment under the infamous Espionage Act of 1917. As the unprecedented U.S. prosecution of Assange reaches a critical stage, a growing number of elite media outlets, human rights advocates and press freedom organizations around the world are demanding his release. All have expressed basic agreement with Nils Melzer, former UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, who describes the case against Assange as a scandal that “represents the failure of Western rule of law.”

The Case Against the Case Against Julian Assange

As the WikiLeaks founder faces a life sentence in American prison, a new book sheds additional light on the official campaign to silence him.

BOOK REVIEW BY STEPHEN ROHDE*

Guilty of Journalism: The Political Case Against Julian Assange

By Kevin Gosztola

The Censored Press / Seven Stories Press

Like the Trump administration that preceded it, the Biden administration is seeking the extradition of WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange to stand trial on an indictment under the infamous Espionage Act of 1917. As the unprecedented U.S. prosecution of Assange reaches a critical stage, a growing number of elite media outlets, human rights advocates and press freedom organizations around the world are demanding his release. All have expressed basic agreement with Nils Melzer, former UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, who describes the case against Assange as a scandal that “represents the failure of Western rule of law.”

Time is running out to correct this failure. Last August, Assange filed an appeal before the U.K. High Court of Justice Administrative Court arguing that his extradition would violate U.K. law because he is being prosecuted for his political opinions and protected speech; that the request itself violates the U.S.-UK Extradition Treaty and international law because it is based on “political offenses;” that the U.S. government has misrepresented the core facts of the case to the British courts; and that the extradition request and its surrounding circumstances constitute an abuse of process. If Assange loses this appeal, his last resort is the European Court of Human Rights.

No one has covered the Assange case more tenaciously, as well as the broader attack on whistleblowers, than journalist Kevin Gosztola. In “Guilty of Journalism: The Political Case Against Julian Assange,” Gosztola expands upon his reports of Assange’s extradition hearings in London during September and October 2020, and in a clear and compelling style, recounts the key events in the case. But he also does more than that. “Guilty of Journalism” offers revelations of egregious conduct by the U.S., including the use of knowingly false testimony, illegal surveillance of Assange and his lawyers and CIA plans to kidnap and assassinate him. These disclosures compound an already shocking tale of injustice at the hands of the U.S. government.

Opening his first chapter with the unequivocal declaration, “Julian Assange is a journalist,” Gosztola never loses sight of the extraordinary contributions WikiLeaks has made through its public disclosures since its founding in 2006. He includes an informative Appendix entitled, “Thirty WikiLeaks Files the Government Doesn’t Want You to Read,” covering climate change and the environment, corporate power, human rights abuses, regime change, foreign policy and U.S. politics. These files, he writes, “reflect the positive impact that WikiLeaks has had by boosting our shared knowledge of a government that rules the most powerful country in the world.”

If Assange loses this appeal, his last resort is the European Court of Human Rights.

In a single volume, Gosztola succeeds in concisely describing the charges and allegations against Assange, the Chelsea Manning court-martial, the origins and history of the Espionage Act, the CIA’s war on WikiLeaks, the surveillance of Assange, FBI abuses, the federal grand jury investigation of Assange, the vital information revealed by WikLeaks, the stories of courageous whistleblowers, how the Assange prosecution threatens freedom of the press, how media organizations aided and abetted the Assange prosecution and the accusation that WikiLeaks helped Russia interfere in the 2016 election. It attains the goal Gosztola set out for himself — that of producing “a guide that will live on as a resource before, during and after Assange’s U.S. trial, should it occur.”

The use of the Espionage Act, signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson two months after the U.S. entry into World War I, strongly suggests to civil libertarians and journalism groups that the Assange prosecution is politically motivated. Wilson, like Trump, demonized dissenters, calling them “creatures of passion, disloyalty and anarchy” who “must be crushed out.” By 1918, 74 left-wing newspapers had been denied mailing privileges. All told, the DOJ has invoked the Espionage Act and the subsequent Sedition Act of 1918 to prosecute more than 2,000 dissenters for allegedly disloyal, seditious or incendiary speech.

Gosztola describes how Assange established WikiLeaks in October 2006 to provide a place for newsworthy information to be released and shared with publications around the world. He notes that in 2013, the Obama DOJ declined to pursue charges against Assange for publishing classified documents because of what officials described as the “New York Times problem”: How could the government prosecute Assange but not other news organizations that also published classified material? On June 19, 2014, human rights and press freedom organizations sent a letter to Attorney General Eric Holder urging him to close all criminal investigations into Assange due to concerns that “actions against Wikileaks undermine the commitment of the U.S. Government to freedom of speech.”

At the extradition hearings in London, the defense counsel demonstrated that Assange is a journalist and that WikiLeaks is a publisher, and as such is entitled to the guarantees of the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution and Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which protect freedom of the press. The prosecution, acting in the name of the United States, argued that “Assange is not being prosecuted for mere publication or reporting,” but instead is being accused of “conspiring” with Manning, “soliciting” classified information, having “direct contact” with Manning and “encouraging” Manning to steal classified documents.

The defense further accused the prosecution of “criminalizing” standard techniques of news gathering used by investigative reporters at mainstream publications such as Le Monde, El País, Der Spiegel, The Guardian, The Washington Postand The New York Times. Their reporters routinely “solicit” classified information, have “direct contact” with sources and “encourage” those sources to obtain classified information. The defense argued that the prosecution turned these traditional news gathering activities into purportedly criminal activity by simply labeling them with the sinister term, “conspiracy.”

According to an affidavit filed by Max Frankel in the Pentagon Papers case when he was Washington Bureau Chief for The New York Times, if the press did not publish official secrets, “there could be no adequate diplomatic, military and political reporting of the kind our people take for granted, either abroad or in Washington and there could be no mature system of communication between the Government and the people.”

Gosztola’s detailed account of how the U.S. spied on Assange and his lawyers will come as a surprise to many readers, as it has received scant coverage in the mainstream media despite being documented in sworn testimony at the extradition hearings and in separate criminal and civil proceedings.

According to various sources, “the intense spying operation primarily occurred between the fall of 2017 and March 2018,” while Assange was in asylum at the Ecuadorian embassy. The espionage operation, which Gosztola vividly describes in scenes reminiscent of a John LeCarre novel, was carried out by Undercover Global, a Spanish company hired by the Ecuador government to provide security for the embassy in London.

On July 19, 2019, attorneys for Assange filed a criminal complaint in Spain, accusing UC Global and its director David Morales of “crimes against privacy,” including violations of the attorney-client privilege, bribery, money laundering and “misappropriation” [embezzlement] against Assange. The Spanish court ordered Morales arrested and charged him with several crimes.

Gosztola’s detailed account of how the U.S. spied on Assange and his lawyers will come as a surprise to many readers, as it has received scant coverage in the mainstream media despite being documented in sworn testimony.

In a statement submitted during Assange’s extradition hearing, Aitor Martinez, an attorney with the law firm representing Assange in the Spanish criminal case, described the “sophisticated espionage operation” that targeted Assange involving the “installation of cameras inside embassy that recorded audio, the installation of hidden microphones to record meetings, the digitization of visitor’s documents and electronic devices and even in some cases physical surveillance, all of which were carried out to feed an FTP server (and later a web repository) that gave remote access, directly through an intermediary, to U.S. intelligence.” Gosztola describes how “materials provided [by UC Global] for the Spanish criminal case showed Morales was in ‘continuous contact’ with U.S. authorities who recommended specific targets for the operation.”

In August 2022, several of those targets, including Margaret Ratner Kunstler and Deborah Hrbak, two attorneys who had represented Assange, along with journalists Charles Glass and John Goetz, sued both the CIA and former CIA director Mike Pompeo as a private individual for allegedly violating their privacy rights. “The United States Constitution shields American citizens from U.S. government overreach even when the activities take place in a foreign embassy in a foreign country,” declared their attorney, Richard Roth. “They had a reasonable expectation that the security guards at the Ecuadorian embassy in London would not be U.S. government spies charged with delivering copies of their electronics to the CIA.”

The court will consider the government’s motions to dismiss in April. Assuming the case moves forward, civil discovery, including the production of documents and emails and a deposition of Pompeo under oath could expose the extent to which the U.S. illegally spied on Assange, his lawyers and others. All of this information could support efforts to dismiss the Assange case on the grounds of prosecutorial misconduct.

One of the more intriguing sections of the book involves the Icelandic FBI informer Sigurdur Igni Thordarson. When the FBI discovered Thordarson in 2011, they thought they had found the perfect witness to prop up their claim that Assange engaged in illegal hacking. Gosztola reveals the bizarre story about how the FBI vouched for Thordarson until the truth got in the way.

In the updated indictment against Assange filed on June 24, 2020, Thordarson was charmingly identified only as “Teenager.” It was alleged that when Assange met the 17-year-old in early 2010, he asked “the Teenager” to “commit computer intrusions and steal additional information, including audio recordings of phone conversations between high-ranking officials” of Iceland, such as members of parliament. The next year, it is alleged, Thordarson became an FBI informant. The indictment describes an elaborate conspiracy of illegal hacking between Thordarson and Assange, including attempting to decrypt a file stolen from an Icelandic bank and how Assange obtained “unauthorized access” through Thordarson to an Icelandic government website “used to track police vehicles.”

The FBI should have been suspicious of Thordarson from the start. Back in 2015 he was charged with “rape, sex with minors, paying for sex with a minor and instigating the prostitution of a minor,” according to the Iceland Monitor. Another Icelandic publication said he “promised to hack the computer network” to change the grades and attendance records of young boys in exchange for sex. While volunteering for WikiLeaks, he embezzled around $50,000 from the organization’s online store and faced a sprawling 18-count prosecution in 2014 that Iceland police said involved “pretending to be Julian Assange online” to trick people into giving him money.

The FBI should have been suspicious of Thordarson from the start.

But Judge Baraitser relied on Thordarson’s allegations to find that, if proven at trial, they would take Assange “outside any role of investigative journalism.” Months after her decision, Bjartmar Alexandersson, a reporter for the Icelandic biweekly newspaper Studin, interviewed Thordarson for nine hours. Thordarson admitted that the allegations against Assange were based on lies. In particular, he admitted that Assange did not ask him to hack Icelandic government computers to obtain “audio recordings of phone conversations between high-ranking officials” of Iceland. He admitted that Assange never “instructed or asked him to access computers in order to find any such recordings” and he admitted that the allegations about Assange attempting to decrypt a file stolen from an Icelandic bank and Assange obtaining “unauthorized access” through Thordarson to an Icelandic government website were all false.

In May 2019, a year before the updated indictment was filed against Assange, the FBI granted Thordarson an immunity deal which guaranteed the DOJ would not share evidence of crimes with “other prosecutorial or law enforcement agencies,” including the Icelandic government. Emboldened, Thordarson went on to commit new crimes and was jailed in Iceland in September 2021.

Gosztola’s account suggests that Thordarson, not Assange, should be the one in jail. On April 13, 2017, CIA director Mike Pompeo told the Center for Strategic and International Studies that WikiLeaks was “a non-state hostile intelligence service” that has “pretended that America’s First Amendment freedoms shield them from justice.” This was all part of the CIA’s public campaign to demonize Assange. But Gosztola describes in detail the CIA’s longstanding secret efforts, going back to the Obama administration, to do far more than slander Assange, according to reporting by Zach Dorfman, Sean Naylor and Michael Isikoff for Yahoo News, based on interviews with 30 former U.S. government officials. Specifically, in 2013 the Obama administration permitted U.S. intelligence agencies to spy on WikiLeaks after WikiLeaks assisted Edward Snowden. To help the CIA pursue Assange and journalists Glenn Greenwald and Laura Poitras as “agents of a foreign power,” U.S. intelligence officials convinced Obama to designate them as “information brokers,” but no criminal charges were filed against the journalists.

In the summer of 2017, Pompeo allegedly proposed kidnapping Assange from the Ecuadorian embassy. And CIA officials allegedly approved a disruption campaign to attack WikiLeaks’ “digital infrastructure” by provoking “internal disputes within the organization by planting damaging information” and even stealing the electronic devices of WikiLeak staff.

“Agency executives requested and received ‘sketches’ of plans for killing Assange and other Europe-based WikiLeaks members” according to what a former intelligence official told Yahoo News. There were discussions “on whether killing Assange was possible and whether it was legal.” Pompeo refused to respond to requests for comment from Yahoo News. Instead, he appeared on conservative radio host Glenn Beck’s show and attacked Isikoff, who co-authored the report. Pompeo claimed Yahoo News didn’t know what the CIA was doing and added, “I make no apologies” because there were “bad actors” who stole “really, really sensitive material.”

In other words, the end justifies the means.

On Oct. 8, 2022, Assange’s wife Stella organized a human chain to surround the UK Parliament. She estimates that at least 5,000 people joined hands to protest Assange’s prosecution. “The London event inspired solidarity actions in Melbourne, Australia, and several U.S. cities, including Washington, D.C., where activists rallied outside the Department of Justice,” Gosztola writes. “Organizers saw this global day of action as a model for future demonstrations to free Assange.”

The Biden administration should heed these calls, uphold the First Amendment, stop pursuing Assange’s extradition and drop all the charges.

In the summer of 2017, Pompeo allegedly proposed kidnapping Assange from the Ecuadorian embassy.

If he doesn’t, and proceeds to prosecute Assange under the 1917 Espionage Act, it will “significantly undermines freedom of expression for journalists around the world,” writes Gosztola, “and give governments with influence or regional power — such as Brazil, China, India, Israel, Russia, Saudi Arabia and Turkey — the green light to assert similar control over their state secrets, and to target journalists, especially if the further release of information would delegitimize their rule.”

If the United States can prosecute an Australian journalist under U.S. law for newsgathering and publishing outside the U.S., why can’t any of the countries Gosztola mentions also prosecute U.S. journalists under their law for newsgathering and publishing outside their countries?

The threat may even be greater and more Orwellian than that. “Let’s expand our imagination,” Gosztola suggests. “Most people use social media applications, which allow them to share anything newsworthy that they obtain firsthand.” The prosecution of Julian Assange has set an alarming precedent that is potentially without limit. The government could use the same charge against anyone — the first, second, or the 100th person — who publishes national defense information without authorization.

In that event, he writes, “We could all be guilty of journalism.”

*Reprinted from Truthdig, April 7, 2023