by Roger Annis, published on Covert Action Magazine, June 21, 2022

Far from condemning the national aspirations of Ukrainians, Putin defends them

In July 2021, Vladimir Putin published a historical essay on Russia and Ukraine on the website of the President of Russia.

The essay is a very informative read, written by someone with a deep knowledge of the subject. It is titled “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians” and was published in Russian, English and Ukrainian.

The essay’s appearance occasioned a round of gratuitous condemnations by Western media and pro-Western academics. The pro-NATO think tank Atlantic Council, for example, published a series of short comments on the essay that carefully avoided any substantive reporting of the essay content.

A member of the Ukrainian Rada (legislature) is quoted:

“Ukraine holds the key to Putin’s dreams of restoring Russia’s great power status. He is painfully aware that without Ukraine, this will be impossible.” He continues, “[The current conflict] is a war for the whole of Ukraine. Putin makes it perfectly clear that his goal is to keep Ukraine firmly within the Russian sphere of influence and to prevent Ukraine’s Euro-Atlantic integration.”

There is nothing new or informative here. The Russian government warned NATO and the world back in December 2021 that a “Euro-Atlantic integration” of Ukraine and the accompanying political and military measures constitute a further escalation of threats against the Russian people and their sovereignty that would not go unanswered. That month, the government published the text of a proposed treaty with the U.S. aimed at resolving the conflict over Ukraine’s future. So, again, the MP is telling us nothing new.

A member of the “Kyiv Security Forum” is also cited by the Atlantic Council survey. He states,

“Putin understands that Ukrainian statehood and the Ukrainian national idea pose a threat to Russian imperialism.”

Here we have an example of the gratuitous term “Russian imperialism” used as an epithet in place of political analysis.

The term is more commonly seen or heard from the Western “leftists’ suffering self-inflicted amnesia over NATO’s decades-long, expansionist aggression against Russia. They are calling for a Russian withdrawal” from Ukraine, which amounts to a call to bow to Ukrainian and NATO aggression.

(A withering rebuttal of Snyder’s extreme-right thesis is contained in a book review by Daniel Lazare published in July 2014 and titled “Timothy Snyder’s lies”.)

So what does President Putin actually say in his 14-page essay? The remainder of this present essay is a summary, concluding with brief comment by this writer on several points of Russian and Soviet history in the 20th century which President Putin’s essay arguably overlooked.

The early history of the future Ukraine

President Putin begins his essay with the following:

First of all, I would like to emphasize that the wall that has emerged in recent years between Russia and Ukraine, between the parts of what is essentially the same historical and spiritual space, to my mind is our great common misfortune and tragedy. These are, first and foremost, the consequences of our own mistakes made at different periods of time. But these are also the result of deliberate efforts by those forces that have always sought to undermine our unity. The formula they apply has been known from time immemorial—divide and rule…

He then writes that modern Russia (during the autocratic monarchy of the Russian Tsars) was “a multilingual and multinational entity.”

Of the emergence of the Ukrainian language, Putin writes,

“Many centuries of fragmentation and living within different states naturally brought about regional language peculiarities, resulting in the emergence of dialects. The vernacular enriched the literary language. Ivan Kotlyarevsky, Grigory Skovoroda, and Taras Shevchenko played a huge role here. Their works are our common literary and cultural heritage… How can this heritage be divided between Russia and Ukraine? And why do it?”

He writes further:

“The south-western lands of the Russian Empire–Malorussia [present-day Ukraine] and Novorossiya, and Crimea–developed as ethnically and religiously diverse entities. Crimean Tatars, Armenians, Greeks, Jews, Karaites, Krymchaks, Bulgarians, Poles, Serbs, Germans, and other peoples lived here. They all preserved their faith, traditions, and customs.

“I am not going to idealize anything. We do know there were the Valuev Circular of 1863 and then the Ems Ukaz of 1876, which restricted the publication and importation of religious and socio-political literature in the Ukrainian language. But it is important to be mindful of the historical context…”

Speaking of historical context, the years that Putin describes here were the years (and several centuries) during which the future NATO powers were waging wars of colonial conquest all around the globe. The U.S. and Canada, in particular, were waging wars of internal conquest against their Spanish and French-language speakers and wars of genocide or policies of cultural genocide (eg. residential schools) against their Indigenous populations. But that is another story for another time.

Putin traces the early development of Ukraine national sentiments during the 19th century.

“The idea of Ukrainian people as a nation separate from the Russians started to form and gain ground among the Polish elite and a part of the Malorussian intelligentsia.”

Then, “Further developments had to do with the collapse of European empires, the fierce civil war that broke out across the vast territory of the former Russian Empire [following the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution] and foreign intervention (ditto).”

This pre-1917 history of the future Russia, Ukraine and Belarus occupies about one-third of Putin’s text. Then we move into the most complex and controversial part of Russian and Ukrainian history, that which was opened by the Russian Revolution of 1917.

Putin traces the efforts of bourgeois forces in Ukraine following the 1917 Revolution in the Tsarist empire to create an independent and pro-Western Ukraine. He describes the role of Symon Petliura and the “Ukrainian People’s Republic” of 1918-20 which Petliura helped to found. That project foundered due to the decisions of Petliura et al. to ally with German imperialism against the lofty goals of the 1917 Revolution.

The most interesting and relevant section of Putin’s 14-page document is his tracing on pages six and seven of the foundation of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in 1922, by which time a Soviet Ukraine had emerged and stabilized. The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic was one of the founding republics of the USSR.

“The right for the republics to freely secede from the Union was included in the text of the Declaration on the Creation of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and, subsequently, in the 1924 USSR Constitution. By doing so, the authors planted in the foundation of our statehood the most dangerous time bomb, which exploded [in 1990-91] the moment the safety mechanism provided by the leading role of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was gone, the party itself collapsing from within. A ‘parade of sovereignties’ followed.”

“In 1954, the Crimean region of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic was given to the Ukrainian SSR, in gross violation of legal norms that were in force at the time.”

His overall judgment of Bolshevik national rights policies is harsh. He writes, “The Bolsheviks treated the Russian people as inexhaustible material for their social experiments. They dreamed of a world revolution that would wipe out national states. That is why they were so generous in drawing borders and bestowing territorial gifts. It is no longer important what exactly the idea of the Bolshevik leaders who were chopping the country into pieces was. We can disagree about minor details, background and logic behind certain decisions. One fact is crystal clear: Russia was robbed, indeed.”

Putin speaks very positively of the economic and social development of Ukraine leading up to the dissolution of the USSR.

“Ukraine and Russia have developed as a single economic system over decades and centuries. The profound cooperation we had 30 years ago is an example for the European Union to look up to. We are natural complementary economic partners. Such a close relationship can strengthen competitive advantages, increasing the potential of both countries.”

He then details the long and sharp economic decline of Ukraine since its post-Soviet independence.

“Who is to blame for this?” he asks. “Is it the people of Ukraine’s fault? Certainly not. It was the Ukrainian authorities who wasted and frittered away the achievements of many generations.”

He writes further:

“Even after the events in Kyiv in 2014 [the anti-Russia coup in February of that year], I charged the Russian government to elaborate options for preserving and maintaining our economic ties within relevant ministries and agencies. However, there was and is still no mutual will to do the same. Nevertheless, Russia is still one of Ukraine’s top three trading partners, and hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians are coming to us to work. They find a welcome reception and support.”

These are historical descriptions worthy of study and debate. They hardly constitute the ideology of an “aggressor Russian state” against Ukraine.

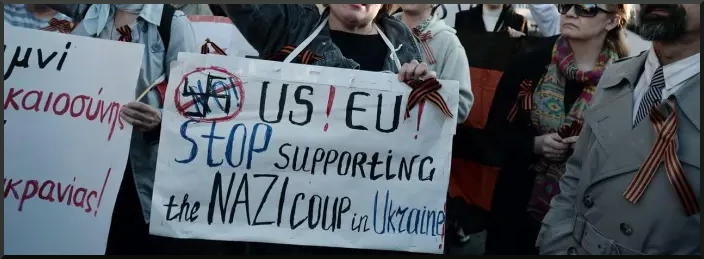

Putin details in several pages the economic, political and cultural decline in Ukraine since 2014. He goes on to summarize:

“The coup d’état [of February 2014 in Kiev] and the subsequent actions of the Kiev authorities inevitably provoked confrontation and civil war.”

“In the anti-Russia project, there is no place either for a sovereign Ukraine or for the political forces that are trying to defend its real independence. Those who talk about reconciliation in Ukrainian society, about dialogue, about finding a way out of the current impasse are labelled as ‘pro-Russian’ agents. But for many people in Ukraine, the anti-Russia project is simply unacceptable. There are millions of such people, but they are not allowed to raise their heads.”

He underlines further his respect for Ukrainian nationhood in the closing section of his essay.

“The entire Ukrainian statehood, as we understand it, is proposed to be further built exclusively on this [anti-Russia] idea. Hate and anger, as world history has repeatedly proven, are a very shaky foundation for sovereignty, fraught with many serious risks and dire consequences.”

Further, “Russia is open to dialogue with Ukraine and ready to discuss the most complex issues. But it is important for us to understand that our Ukrainian partner defend its national interests not by serving someone else’s, that it not be a tool in someone else’s hands to fight against us.”

Putin closes his essay with these three paragraphs:

We respect the Ukrainian language and traditions. We respect Ukrainians’ desire to see their country free, safe and prosperous.

I am confident that true sovereignty of Ukraine is possible only in partnership with Russia. Our spiritual, human and civilizational ties formed for centuries and have their origins in the same sources, they have been hardened by common trials, achievements and victories. Our kinship has been transmitted from generation to generation. It is in the hearts and the memory of people living in modern Russia and Ukraine, in the blood ties that unite millions of our families. Together we have always been and will be many times stronger and more successful. For we are one people.

Today, these words may be perceived by some people with hostility. They can be interpreted in many possible ways. Yet, many people will hear me. And I will say one thing – Russia has never been and will never be ‘anti-Ukraine.’

It is impossible to read Vladimir Putin’s words as those of a “Great Russian chauvinist,” as pro-NATO apologists, including self-declared socialists, are doing (see here and here).

Meanwhile, the real great power chauvinists and their ideologues—in the NATO countries—have little to say in answer to Putin’s carefully presented history. They resort to superficial name-calling and epithets.

Rethinking the national self-determination policies of Lenin and his Bolshevik Party

President Putin’s essay should serve to stimulate more historical study and debate of Russia, Ukraine and the historical relations between the two.

The self-determination policies of the 1917 Revolution should be front and center in that. Sadly, the prevailing anti-Russian propaganda in the West gets in the way of this, including among historians and left-wing thinkers. Instead, all we get are blind condemnations.

Two vital areas of study of the self-determination policy are largely missing from the president’s essay.

One is the portrait of the world and the far-reaching aspirations for national self-determination or independence at the outset of World War One.

The self-determination policies of Lenin and the Bolsheviks were crafted precisely in response to the clamor for national freedom by the subjects of the large empires of the day—Russia, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Britain, France, the USA and others. Self-determination for the oppressed peoples of the Russian Tsarist Empire, in particular, was a key driving force of the 1917 Revolution which began, let us recall, with the toppling of the Tsarist monarchy in February of that year.

Two is the calamitous, four-year military intervention against the early Soviet Union by the world’s imperialist powers, aimed at overthrowing the Bolshevik-led government and the 1917 Revolution itself.

The extreme economic hardship caused by the blockade contributed greatly to the factional breakdown of the Soviet government and leadership following the death of Lenin in 1924.

Overall, imperialist intervention and blockades contributed greatly to the rise of authoritarian socialism in the early Soviet Union and to its eventual demise decades later.

Looking back, one can fairly judge and criticize the self-determination policies of the Bolshevik Revolution. But the fact that the most idealistic and far-reaching of these policies did not succeed or were seriously compromised is not an argument per se against them. Rather, it is an argument for more study and learning of the exact reasons why some of the policies (not the entirety) failed or were compromised during the 1930s and in later decades.

The self-determination policies of the early Russian Revolution were astonishing and world-shaking in their scope. They helped to transform the Russian empire into the modern state of the Soviet Union. They inspired peoples around the world to take up struggle against imperialism and for national independence, including another world-shaking event, the Chinese Revolution of 1949.

It is a truly federated and multilingual country. Examples of this were seen recently in the referendum vote in Crimea in 2014 to secede from Ukraine and join the Russian Federation, and in the rebellion of the people of Donbas against the extreme-right coup in Ukraine in 2014.

Vladimir Putin voiced this at a meeting of Russia’s National Security Council on March 3, 2022 which honored the soldiers of the Russian army fighting in Ukraine.

He told the meeting:

“I am a Russian. As they say, all my relatives are Ivans and Marias. But when I see heroes like this young man, Nurmagomed Gadzhimagomedov, a resident of Dagestan and an ethnic Lak, and our other soldiers, I can hardly stop myself from saying: I am a Lak, a Dagestani, a Chechen, an Ingush, a Russian, a Tatar, a Jew, a Mordovian, an Ossetian… It is impossible to name all of the more than 300 nationalities and ethnic groups that live in Russia. I think you can understand me. I am proud to be part of this world, part of our powerful and strong multinational people of Russia.”

These and many other such examples which could be cited are compelling evidence that the embers of the self-determination policies of the Bolshevik Revolution remain alive in the Russian Federation and the former Soviet sphere. Even more, these policies remain extremely relevant in an imperialist-dominated world that routinely seeks to crush self-determination and national independence aspirations of oppressed peoples.

The principles of peace, social justice and national determination are often voiced but always trampled into the dirt by the imperialist powers that dominate todays’ planet and human society. But that doesn’t mean the policies should be discarded. Rather, it means we must redouble efforts to realize them.

Roger Annis is a retired aerospace worker and resident in Vancouver, Canada. He publishes the website and blog A Socialist In Canada. Roger can be reached at contact@socialistincanada.ca.

One comment