This is a rather long, but very descriptive account of one day in the ongoing extradition trial of Wikileaks publisher Julian Assange. It is important to keep some awareness of this critically important test of our first amendment rights and international law (the Extradition Treaty between the US and the UK does not allow extradition for political reasons) as well as the unfolding of the ongoing efforts to punish and torment Julian for telling the truth to the public about illegal government actions that they would have preferred to keep secret. There are more of Craig’s articles published on Consortium News, and I highly recommend Joe Lauria’s daily 10 minute updates on the trial. Joe and Craig are both in London to view the proceedings first hand. (JB)

by Craig Murray: Your Man in the Public Gallery, published on Consortium News, September 18, 2020

A less dramatic day, but marked by a brazen and persistent display of this U.S. government’s insistence that it has the right to prosecute any journalist and publication, anywhere in the world, for publication of U.S. classified information. This explicitly underlay the entire line of questioning in the afternoon session.

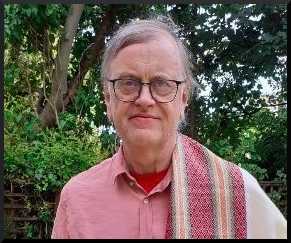

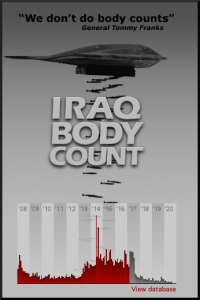

The morning opened with Professor John Sloboda of Iraq Body Count. He is a professor of psychology and a musicologist who founded Iraq Body Count together with Damit Hardagan, and was speaking to a joint statement by both of them.

Sloboda stated that Iraq Body Count attempted to build a database of civilian deaths in Iraq based on compilation of credible published material. Their work had been recognised by the UN, EU and the Chilcot Inquiry.

He stated that protection of the civilian population was the duty of parties at war or in occupation, and targeting of civilians was a war crime.

WikiLeaks’ publication of the Iraq War Logs had been the biggest single accession of material to the Iraq Body Count and added 15,000 more civilian deaths, plus provided extra detail on many deaths which were already recorded. The logs or Significant Activity Reports were daily patrol records, which recorded not only actions and consequent deaths the patrols were involved in, but also deaths which they came across.

After the publication of the Afghan war logs, Iraq Body Count (IBC) had approached WikiLeaks to be involved in the publication of the Iraq equivalent material. They thought they had accumulated a particular expertise which would be helpful. Julian Assange had been enthusiastic and had invited them to join the media consortium involved in handling the material.

There were 400,000 documents in the Iraq War Logs. Assange had made very plain that great weight must be placed on document security and with careful redaction to prevent, in particular, names from being revealed which could identify individuals who might come to harm. It was however impossible to redact that volume of documents by hand. So WikiLeaks had sought help in developing a software that would help. IBC’s Damit Hardagan had devised the software which solved the problem.

Essentially, this stripped the documents of any word not in the English dictionary. Thus Arabic names were removed, for example.

In addition other potential identifiers such as occupations were removed. A few things like key acronyms were added to the dictionary. The software was developed and tested on sample batches of telegrams until it worked well.

Julian Assange was determined redaction should be effective and resisted pressure from media partners to speed up the process. Assange always meticulously insisted on redaction. On balance, they overredacted for caution. Sloboda could only speak on the Iraq War Logs, but these were published by WikiLeaks in a highly redacted form which was wholly appropriate.

Cross Examination

Joel Smith then stood up to cross-examine for the U.S. government. As is the standard prosecution methodology in this hearing, Smith set out to trash the reputation of the witness.

[I found this rather ironic, as Iraq Body Count has been rather good for the U.S. government. The idea that in the chaos of war every civilian death is reported somewhere in local media is obviously nonsense. Each time the Americans flattened Fallujah and everyone in it, there was not some little journalist writing up the names of the thousands of dead on a miraculously surviving broadband connection. Iraq Body Count is a good verifiable minimum number of civilian deaths, but no more, and its grandiose claims have led it to be used as propaganda for the “war wasn’t that bad” brigade. My own view is that you can usefully add a zero to their figures. But I digress.]

Smith established that Sloboda’s qualifications are in psychology and musicology, that he had no expertise in military intelligence, classification and declassification of documents or protection of intelligence sources. Smith also established that Sloboda did not hold a U.S. security clearance (and thus was in illegal possession of the information from the viewpoint of the U.S. government). Sloboda had been given full access to all 400,000 Iraq War Logs shortly after his initial meeting with Assange. They had signed a non-disclosure agreement with the International Committee of Investigative Journalists. Four people at IBC had access. There was no formal vetting process.

To give you an idea of this cross-examination:

Smith Are you aware of jigsaw identification?

Sloboda It is the process of providing pieces of information which can be added together to discover an identity.

Smith Were you aware of this risk in publishing?

Sloboda We were. As I have said, we redacted not just non-English words but occupations and other such words that might serve as a clue.

Smith When did you first speak to Julian Assange?

Sloboda About July 2010.

Smith The Afghan war logs were published in July 2010. How long after that did you meet Assange?

Sloboda Weeks.

…..

Smith You talk of a responsible way of publishing. That would include not naming U.S. informants.

Sloboda Yes.

Smith Your website attributes killings to different groups and factions within the state as well as some outside influences. That would indicate varied and multiple sources of danger to any U.S. collaborators named in the documents.

Sloboda Yes.

Smith Your statement spoke of a steep learning curve from the Afghan war logs that had to be applied to the Iraq War Logs. What does that mean?

Sloboda It means WikiLeaks felt that mistakes were made in publishing the Afghan war logs that should not be repeated with the Iraq War Logs.

Smith Those mistakes involved publication of names of sources, didn’t they?

Sloboda Possibly, yes. Or no. I don’t know. I had no involvement with the Afghan war logs.

Smith You were told there was time pressure to publish?

Sloboda Yes, I was told by Julian he was put under time pressure and I picked it up from other media partners.

Smith And it was IBC who came up with the software solution, not Assange?

Sloboda Yes.

Smith How long did it take to develop the software?

Sloboda A matter of weeks. It was designed and tested then refined and tested again and again. It was not ready by the original proposed publication date of the Iraq War Logs, which is why the date was put back.

Smith Redaction then would remove all non-English words. But it would still leave vital clues to identities, like professions? They had to be edited by hand?

Sloboda No. I already said that professions were taken out. The software was written to do that.

Smith It would leave in buildings?

Sloboda No, other words like “mosque” were specifically removed by the software.

Smith But names which are also English words would be left in. Like Summers, for example.Sloboda I don’t think there are any Iraqi names which are also English words.

Smith Dates, times, places?

Sloboda I don’t know.

[Sloboda was obviously disconcerted by Smith’s quickfire technique and had been rattled into firing back equally speedy and short answers. If you think about it a moment, Iraqi street names are generally not English words.]

Smith Vehicles?

Sloboda I don’t know.

Smith You said at a press conference that you had “merely scratched the surface” in looking at the 400,000 documents.

Sloboda Yes.

Smith You testified that Julian Assange shared your view that the Iraqi War Logs should be published responsibly. But in a 2010 recorded interview at the Frontline Club, Mr. Assange called it regrettable that informants were at risk, but said WikiLeaks only had to avoid potential for unjust retribution; and those that had engaged in traitorous behavior or had sold information ran their own risk. Can you comment?

Sloboda No. He never said anything like this to me.

Smith He never said he found the process of redaction disturbing?

Sloboda No, on the contrary. He said nothing at all like that to me. We had a complete meeting of minds on the importance of protection of individuals.

Smith Not all the logs related to civilian deaths.

Sloboda No. The logs put deaths in four categories. Civilian, host nation (Iraqi forces and police), friendly nation (coalition forces) and enemy. The logs did not always detail the actions in which deaths occurred. Sometimes the patrols were the cause, sometimes they detailed what they came across. We moved police deaths from the host nation to the civilian category.

[One of the problems I personally have with IBC’s approach is that they accepted U.S. forces’ massive over-description of the dead as “hostile. Obviously when U.S. forces killed someone they had an incentive to list them as “hostile” and not “civilian”.]

Smith Are you aware that when the Iraq Significant Activity Reports (war logs) were released online in October 2010, they did in fact contain unredacted names of cooperating individuals?

Sloboda No, I am not aware of that.

Smith now read an affidavit from a new player [Dwyer?] which stated that the publication of the SARs put co-operating individuals in grave danger. Dwyer purported to reference two documents which contained names. Dwyer also stated that “military and diplomatic experts” confirmed individuals had been put in grave danger.

Smith How do you explain that?

Sloboda I have no knowledge. It’s just an assertion. I haven’t seen the documents referred to.

Smith Might this all be because Mr. Assange “took a cavalier attitude to redaction”?

Sloboda No, definitely not. I saw the opposite.

Smith So why did it happen?

Sloboda I don’t know if it did happen. I haven’t seen the documents referred.

That ended Sloboda’s evidence. He was not re-examined by the defence.

I have no idea who “Dwyer” — name as heard — is or what evidential value his affidavit might hold.

It is a constant tactic of the prosecution to enter highly dubious information into the record by putting it to witnesses who have not heard of it. The context would suggest that “Dwyer” is a U.S. government official. Given that he claimed to be quoting two documents he was alleging WikiLeaks had published online, it is also not clear to me why those published documents were not produced to the court and to Sloboda.

Next Witness: Carey Shenkman

We now come to the afternoon session. I have a difficulty here. The next witness was Carey Shenkman, an academic lawyer in New York who has written a book on the history of the Espionage Act of 1917 and its use against journalists.

Now partly because Shenkman was a lawyer being examined by lawyers, at times his evidence included lots of case names being thrown around the significance of which was not entirely clear to the layman. I often could not catch the names of the cases. Even if I produced a full transcript, large chunks of it would be impenetrable to those from a non-legal background, including me, without a week to research it. So if this next reporting is briefer and less satisfactory than usual, it is not the fault of Carey Shenkman.

This evidence was none the less extremely important because of the clear intent shown by the U.S. government in cross examination to now interpret the Espionage Act in a manner that will enable them to prosecute journalists wholesale.

Shenkman began his evidence by explaining that the 1917 Espionage Act under which Assange was charged dates from the most repressive period in U.S. history, when Woodrow Wilson had taken the U.S. into the First World War against massive public opposition.

It had been used to imprison those who campaigned against the war, particularly labour leaders. Wilson himself had characterized it as “the firm hand of stern repression.” Its drafting was extraordinarily broad and it was on its surface a weapon of political persecution.

The Pentagon Papers case had prompted Harold Edgar and Benno Schmidt to write a famous analysis of the Espionage Act published in the Columbia Law Review in 1973.

It concluded that there was incredible confusion about the meaning and scope of the law and capacity of the government to use it. It gave enormous prosecutorial discretion on who to prosecute and depended on prosecutors behaving wisely and with restraint. There was no limit on strict liability. The third or fifth receiver in the chain of publication of classified information could be prosecuted, not just the journalist or publisher but the person who sells or even buys or reads the newspaper.

Shenkman went through three historic cases of potential criminal prosecution of media under the Espionage Act. All had involved direct presidential interference and the active instigation of the attorney general. All had been abandoned before the grand jury stage because the Justice Department had opposed proceeding. Their primary concern had always been how to distinguish media outlets. If you prosecuted one, you had to prosecute them all.

[An aside for my regular readers — that is a notion of fairness entirely absent from James Wolff, Alex Prentice and the Crown Office in Scotland].

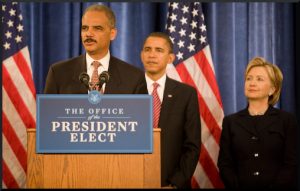

The default position had become that the Espionage Act was used against the whistleblower but not against the publisher or journalist, even when the whistleblower had worked closely with the journalist. President Barack Obama had launched the largest ever campaign of prosecution of whistleblowers under the Espionage Act. He had not prosecuted any journalist for publishing the information they leaked.

Cross Examination

Claire Dobbins then rose to cross examine on behalf of the U.S. government, which evidently is not short of a penny or two to spend on multiple counsel. Dobbins looks a pleasant and unthreatening individual. It was therefore surprising that when she spoke, out boomed a voice that you would imagine as emanating from the offspring of Ian Paisley and Arlene Foster. This impression was of course reinforced by her going on to advocate for harsh measures of repression.

Dobbins started by stating that Shenkman had worked for Julian Assange.

Shenkman clarified that he had worked in the firm of the great lawyer Michael Ratner, who represented Assange. But that firm had been dissolved on Ratner’s death in 2016 and Shenkman now worked on his own behalf. This all had no bearing on the history and use of the Espionage Act, on which he had been researching in collaboration with a well-established academic expert.

Dobbins than asked whether Shenkman was on Assange’s legal team.

He replied no.

Dobbins pointed to an article he had written with two others, of which the byline stated that Shenkman was a member of Julian Assange’s legal team.

Shenkman replied he was not responsible for the byline. He was a part of the team only in the sense that he had done a limited amount of work in a very junior capacity for Michael Ratner, who represented Assange. He was “plankton” in Ratner’s firm.

Dobbins said that the article had claimed that the U.K. was illegally detaining Assange in the Ecuadorian embassy.

Shenkman replied that was the view of the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, with which he concurred.

Dobbins asked if he stood by that opinion.

Shenkman stated that he did, but it bore no relationship to his research on the history of the Espionage Act on which he was giving evidence.

Dobbins asked whether, having written that article, he really believed he could give objective evidence as an expert witness.

Shenkman said yes he could, on the history of use of the Espionage Act. It was five years since he had left the Ratner firm. Lawyers had all kinds of clients who very loosely related in one way or another to other work they did. They had to learn to put that aside and be objective.

Dobbins said that the 2013 article stated that Assange’s extradition to the United States was almost certain. What was the basis of this claim?

Shenkman replied that he had not been the main author of that article, with which three people were credited. He simply could not recall that phrase at this time or the thought behind it. He wished to testify on the history of the Espionage Act, of which he had just written the first historical study.

Dobbins asked Shenkman if he was giving evidence pro bono?

He replied no, he was appearing as a paid expert witness to speak about the Espionage Act.

Dobbins said that the defence claimed that the Obama administration had taken the decision not to prosecute Assange. But successive court statements showed that an investigation was still ongoing (Dobbins took him through several of these, very slowly). If Assange had really believed the Obama administration had dropped the idea of prosecution, then why would he have stayed in the embassy?

Shenkman replied that he was very confused why Dobbins would think he had any idea what Assange knew or thought at any moment in time. Why did she keep asking him questions about matters with which he had no connection at all and was not giving evidence?

But if she wanted his personal view, there had of course been ongoing investigations since 2010. It was standard Justice Department practice not to close off the possibility of future charges. But if [then Attorney General Eric] Holder and Obama had wanted to prosecute, wouldn’t they have brought charges before they left office and got the kudos, rather than leave it for Trump?

Dobbins then asked a three-part question that rather sapped my will to live. Shenkman sensibly ignored it and asked his own question instead. “Did I anticipate this indictment? No, I never thought we would see something as political as this. It is quite extraordinary. A lot of scholars are shocked.”

Dobbins now shifted ground to the meat of the government position. She invited Shenkman to agree with a variety of sentences cherry picked from U.S. court judgements over the years, all of which she purported to show an untrammeled right to put journalists in jail under the Espionage Act.

She started with the Morison Case in the Fourth Appellate Circuit Court and a quote to the effect that “a government employee who steals information is not entitled to use the First Amendment as a shield.”

She invited Shenkman to agree.

He declined to do so, stating that particular circumstances of each case must be taken into consideration and whistle blowing could not simply be characterized as stealing. Contrary opinions exist, including a recent Ninth Appellate Circuit Court judgement over Edward Snowden. So no, he did not agree. Besides Morison was not about a publisher. The Obama prosecutions showed the historic pattern of prosecuting the leaker not the publisher.

Dobbins then quoted a Supreme Court decision with a name I did not catch, and a quote to the effect that “the First Amendment cannot cover criminal conduct.” She then fired another case at him and another quote. She challenged him to disagree with the Supreme Court.

Shenkman said the exercise she was engaged in was not valid. She was picking individual sentences from judgements in complex cases, which involved very different allegations. This present case was not about illegal wiretapping by the media like one she quoted, for example.

Dobbins then asked Shenkman whether unauthorized access to government databases is protected under the First Amendment.

He replied that this was a highly contentious issue. There were, for example, a number of conflicting judgements in different appellate circuits about what constituted unauthorised access.

Dobbins asked if hacking a password hash would be unauthorized access.

Shenkman replied this was not a simple question. In the present case, the evidence was the password was not needed to obtain documents. And could she define “hacking” in law?

Dobbins said she was speaking in layman’s terms.

Shenkman replied that she should not do that. We were in a court of law and he was expected to show extreme precision in his answers. She should meet the same standard in her questions.

Finally Dobbins unveiled her key point. Surely all these contentious points were therefore matters to be decided in the U.S. courts after extradition?

No, replied Shenkman. Political offenses were a bar to extradition from the U.K. under U.K. law, and his evidence went to show that the decision to prosecute Assange under the Espionage Act was entirely political.

Mrs Dobbins will resume her cross examination of Shenkman tomorrow.

Comment

I have two main points to make. The first is that Shenkman was sent a 180-page evidence bundle from the prosecution on the morning of his testimony, at 3 a.m. his time, before giving evidence at 9 a.m. A proportion of this was entirely new material to him. He is then questioned on it. This keeps happening to every witness. On top of which, like almost every witness, his submitted statement addressed the first superseding indictment not the last-minute second superseding indictment which introduces some entirely new offenses. This is a ridiculous procedure.

My second is that, having been very critical of Judge Baraitser, it would be churlish of me not to note that there seems to be some definite change in her attitude to the case as the prosecution makes a complete horlicks of it. Whether this makes any long term difference I doubt. But it is pleasant to witness.

It is also fair to note that Baraitser has so far resisted strong U.S. pressure to prevent the defence witnesses being heard at all. She has decided to hear all the evidence before deciding what is and is not admissible, against the prosecution’s desire that almost all the defence witnesses are excluded as irrelevant or unqualified. As she will make that decision when considering her judgement, that is why the prosecution spend so much time attacking the witnesses ad hominem rather than addressing their actual evidence. That may well be a mistake.

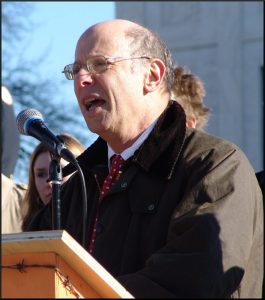

*Featured Image: Craig Murray outside the Courthouse

Craig Murray is an author, broadcaster and human rights activist. He was British ambassador to Uzbekistan from August 2002 to October 2004 and rector of the University of Dundee from 2007 to 2010.