by Vijay Prashad, published on Consorteum News, February 17, 2020

originally published on Tricontinental Institute, February 7, 2020

In November 2019, the Bolivian army – with a nudge from the shadows – told its President Evo Morales Ayma to resign. Morales would eventually go to Mexico and then seek asylum in Argentina. Jeanine Áñez, a far-right politician who was not in the line of succession, seized power; the military, the fascistic civil society groups and sections of the evangelical church backed her. Áñez said that she would hold elections soon, but that she would herself not stand in them.

Áñez set the date of election for May 3. Despite her promise, she will stand for the presidency. The conditions for the election are so poor that the United Nations has publicly worried about the “exacerbated polarization” in the country. There is ample evidence of intimidation and violence being used by the interim government and its far-right allies against the members of the Movement to Socialism (MAS) – Morales’s party – and its supporters. Even though early polls indicate that MAS is ahead, with its candidates Luis Arce Catacora (president) and David Choquehuanca Céspedes (vice president), there is every indication that dirty tricks are afoot to create fear in society and to disenfranchise sections of the Bolivian citizenry.

Áñez attempted to suffocate society with great force after the November coup, but pressure from MAS militants and its base – as well as the United Nations, the European Union, and the Catholic Church – have forced Áñez to send Bolivian forces to the barracks and to withdraw the decree that granted the military immunity for its violence. This has not stopped Áñez and her far-right base from using the state to oppress MAS – including arresting over 100 MAS officials and threatening 592 more with charges that include sedition and terrorism (Morales already faces these charges). Arturo Murillo, Áñez’s interior minister, has called for the disenfranchisement of voters from the Chapare, an area that almost completely supports MAS.

Áñez attempted to suffocate society with great force after the November coup, but pressure from MAS militants and its base – as well as the United Nations, the European Union, and the Catholic Church – have forced Áñez to send Bolivian forces to the barracks and to withdraw the decree that granted the military immunity for its violence. This has not stopped Áñez and her far-right base from using the state to oppress MAS – including arresting over 100 MAS officials and threatening 592 more with charges that include sedition and terrorism (Morales already faces these charges). Arturo Murillo, Áñez’s interior minister, has called for the disenfranchisement of voters from the Chapare, an area that almost completely supports MAS.

On Jan. 9, the U.S. government sent a USAID team to offer “technical support” for the election; Morales had expelled USAID in 2013 on the grounds that it was working to undermine his government. “Technical support” is another way of saying interference in the elections.

To head Bolivia’s Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE), Áñez brought back Salvador Romero, who had been in charge of this body from 2003 to 2008. After Morales won his first election, he told Romero that his term would not be extended. Romero rushed to the U.S. embassy in La Paz to complain to U.S. Ambassador Phillip Goldberg, whom Morales expelled from Bolivia in 2008 (Goldberg is now the U.S. ambassador in Colombia). The United States took care of Romero; he was appointed to head the National Democratic Institute in Honduras, a quasi-independent agency of the U.S. ruling class that works towards “democracy promotion” – in other words, towards installing pro-U.S. and pro-capitalist parties into office in places such as Bolivia and Honduras. In the first election after the 2009 coup in Honduras, Romero provided a patina of legitimacy for the violence that led to the 2013 election of the far-right candidate, Juan Orlando Hernández.

A few days before the 2013 vote, two leaders of the National Centre of Farmworkers (CNTC), María Amparo Pineda Duarte and Julio Ramon Maradiaga, were returning home after an election training; they were supporters of the left-wing Libre party. They were killed and beheaded. Florencia López, a relative of María, said, “They are people who are forgotten” (“son personas que son olvidadas”).

But we remember them. They are a memory of the way in which U.S.-driven “democracy protection” works in elections in places such as Honduras and Bolivia.

The May 3 Elections

On Nov. 10, 2019, a coup d’état took place in Bolivia. The commander-in-chief of the Bolivian Armed Forces asked President Evo Morales to resign. The police had already mutinied, and society had already been destabilized – this had been triggered by a presidential election whose results had not been recognized by the opposition and whose results had been suspiciously discredited by the Organisation of American States (OAS). Two days after Morales resigned, a largely unheard-of opposition politician, Jeanine Áñez, declared herself to be the interim president without the necessary quorum in the Plurinational Legislative Assembly, where Morales’s party, the Movement to Socialism (MAS) holds the majority of the seats.

The new government said that it would only remain until elections could be held. However, from the inauguration of Áñez, the government has prosecuted a policy of repression against the leaders and militants of MAS and against social movements (36 people have died), and it has implemented political and economic policy changes that are inspired by the neoliberal agenda driven by the U.S. government. The interim government has a racist, patriarchal, and fundamentalist character, as expressed through symbolic and reactionary acts of violence, such as the denigration of the Wiphala (a flag that represents the diversity of the indigenous people and nations of Bolivia).

In January 2020, the government announced that the presidential and legislative elections will be held on May 3. The election process began under conditions of severely restricted democratic freedom; by January’s end, the interim government had militarized the country’s main cities to prevent any possible demonstrations. It has continued to harass and persecute members of MAS government who have sought asylum in foreign embassies for fear of their lives. The interim government has closed more than fifty radio stations; it has accused them of sedition and of incitement to violence for having broadcast stories critical of the interim government.

A number of coalitions of political parties have registered tickets for the presidential election. The candidates for MAS are Luis Arce Catacora (president) and David Choquehuanca Céspedes (vice president). Catacora was the minister of economy and public finance under Morales and the architect of the administration’s economic success. Céspedes was the foreign minister in that government. He managed Bolivia’s policy of international sovereignty and is an important person to Bolivia’s indigenous and peasant movements. Early polls show that the MAS ticket is in first place.

In the first days of February, one of Morales’s two attorneys was detained. The government sought to arrest MAS’s attorney, who was in the midst of registering candidates for the May elections. Threats began to mount against Luis Arce Catacora, the presidential candidate of MAS, as he returned to Bolivia, including the possibility of his arrest. Parts of the country with the deepest support for MAS face repression and threats that their right to vote might be withdrawn.

The interim president – Áñez – announced that she will be a candidate for the presidency without leaving her current position; this is in contradiction to her earlier statements. The other candidates who supported the coup d’état nonetheless criticized her move, which validates the coup character of this government and its officials.

The international community must be aware of the danger that the interim government will ban MAS, commit fraud, and destroy the possibility of democracy in Bolivia.

Why the US Coup & Intervention?

Bolivia has the largest known lithium reserves in the world (with the potential to produce 20 percent of global lithium). Lithium is a central component for batteries, which are used in electric cars, laptops, watches, and cell phones, as well as for the storage of renewable energy. The largest deposit of lithium in Bolivia is in the Uyuni salt flats in the department of Potosí, where Morales’ administration had planned to extract it through the state-owned company.

Bolivia has considerable hydrocarbon reserves – especially natural gas – which it supplies to Brazil and Argentina. When Morales took office, an early measure was to nationalize these resources and develop state control over them. A substantial part of the hydrocarbon reserves is located in Santa Cruz, in Bolivia’s eastern region. This is also the home of its agribusiness, especially soy. The government of Santa Cruz and its civic committee have been the base of the opposition to Morales from the very beginning and played a central role in the social destabilization that led to the coup.

Morales won the 2005 election with more than 50 percent of the vote. In his first term (2006-2010), his MAS-led administration nationalized hydrocarbon production and other strategic parts of the economy; it pushed for land reform; and it reformed the constitution through a Constituent Assembly process, which became the foundation for the formation of Bolivia as a Plurinational State. Morales, from 2006, drove a policy to substantially improve all social indicators; his government was able to reduce poverty (38.2 percent to 15.2 percent), eradicate illiteracy, and improve hygiene as well as life expectancy (by nine years).

Despite being a majority indigenous country, Bolivia has been governed by a caste that is predominantly made up of groups who consider themselves to be white. Indigenous people have long suffered from subjugation, racism and discrimination in political, economic and social spheres at the hands of this governing caste.

Morales’ government represented a complete shift in the social sense. It forcefully combatted the violence of racism and the xenophobic discourse about indigenous peoples and cultures; this was a government committed to ending the structure and culture of colonial domination. The symbols that define the interim government, on the other hand, are marked by racial hatred and fascism; this is what has sustained them in their fiercely racist attacks against MAS.

The U.S. government hastily recognized and warmly welcomed Áñez into the diplomatic world; it immediately pressured the Mexican government, and then later the Argentinian government, to deny asylum requests from members of MAS and from Morales’ administration. It is now clear that the U.S. government participated in the preparation and the execution of the coup against Morales. There was an immediate dislike by the US of Morales for his policy of economic resource nationalism, for his expulsion of the US Agency for International Development (USAID) from Bolivia, for his suspension of the US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) military eradication programme against coca, and for his denunciations in international forums of the US policy of economic, military, and political intervention.

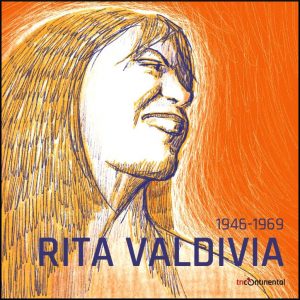

Rita Valdivia, a young Bolivian woman who escaped from an abusive father and into the world of revolutionary struggle and poetry, joined the Bolivian National Liberation Army (ELN). Poetry gave her voice; the revolutionary struggle put that voice into motion. Ernesto “Che” Guevara was killed in 1967, the year that Rita Valdivia went to Cuba for training. The leader of the ELN – Guido Álvaro ‘Inti’ Peredo Leigue (a member of the Bolivian Communist Party) – put her in charge of revolutionary activity in her native Cochabamba, where she returned after her training in Cuba. In 1968, Inti wrote his iconic text, “Volveremos a las montañas” (“We will return to the mountains”), a pledge to continue the fight against the oligarchy and its army. On the night of July 13, 1969, Valdivia, also known by the name “Comandante Maya,” and her comrades went to a meeting at a safe house; they had been betrayed, and she was gunned down. She was 23. Inti was killed the following September.

Rita Valdivia, a young Bolivian woman who escaped from an abusive father and into the world of revolutionary struggle and poetry, joined the Bolivian National Liberation Army (ELN). Poetry gave her voice; the revolutionary struggle put that voice into motion. Ernesto “Che” Guevara was killed in 1967, the year that Rita Valdivia went to Cuba for training. The leader of the ELN – Guido Álvaro ‘Inti’ Peredo Leigue (a member of the Bolivian Communist Party) – put her in charge of revolutionary activity in her native Cochabamba, where she returned after her training in Cuba. In 1968, Inti wrote his iconic text, “Volveremos a las montañas” (“We will return to the mountains”), a pledge to continue the fight against the oligarchy and its army. On the night of July 13, 1969, Valdivia, also known by the name “Comandante Maya,” and her comrades went to a meeting at a safe house; they had been betrayed, and she was gunned down. She was 23. Inti was killed the following September.

In Cantaura (Venezuela), there is a people’s medical center that is named after Comandante Maya, which is where I first heard of her. Comandante Maya’s poem – “Defensa a la calle” (“Defending the Street,” as translated by Margaret Randall) – teaches us that even in the worst moments in Bolivia, there are people struggling for their rights and aspirations, opening their fists to the world:

Me he cansado de retener otros mundos

en mi puño.

Lo abro de golpe.I am tired of holding other worlds

in my fist.

I open it suddenly.

Vijay Prashad is an Indian historian, editor and journalist. He is a writing fellow and chief correspondent at Globetrotter, a project of the Independent Media Institute. He is the chief editor of LeftWord Books and the director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. He has written more than twenty books, including The Darker Nations: A People’s History of the Third World (The New Press, 2007), The Poorer Nations: A Possible History of the Global South (Verso, 2013), The Death of the Nation and the Future of the Arab Revolution (University of California Press, 2016) and Red Star Over the Third World (LeftWord, 2017).