by Owen Schalk, published on CovertAction Magazine, August 3, 2022

The United States does the heavy lifting, but Canada provides consistent behind-the-scenes support to enable the plunder of Congo and other nations in the Global South.

On October 14, 2004, a group of ten armed men took control of the city of Kilwa in the eastern Katanga province of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and promptly declared the province’s independence. Part of an obscure secessionist movement called the Mouvement Révolutionnaire pour la Liberation du Katanga, they hoped to attain local support by playing to local grievances against the central government and the Montréal-based company Anvil Mining, which owned the nearby Dikulushi copper mine.

Many locals felt that Anvil, which allegedly operated “with the support of certain members of the presidential team who had links with Katanga businessmen,” did not contribute enough of its revenues from the mine ($10-$20 million annually) to the surrounding community, and it appears that the secessionists felt they could use local distaste for the mining company and its rich backers in Kinshasa and Katanga to their advantage.[1]

Predictably, Anvil Mining was displeased by the uprising, which blocked the company’s access to the port in Kilwa, from which they exported copper and silver for processing.

The day after the rebels took Kilwa, Congolese soldiers stormed the town and killed 73 villagers, 20 of them by summary execution, and buried their corpses in mass graves. With this massacre, the town was returned to central government control.

Survivors of the violence reported the arbitrary killing of civilians, looting, rape and torture by Congolese troops. They also reported that the soldiers were driving vehicles provided to them by Anvil Mining.

A United Nations investigation found that the Canadian-Australian company logistically and financially supported the military action against Kilwa. The UN mission and later investigative work revealed that Anvil had provided the perpetrators of the killings, who were operating under orders to “shoot anything that moved,” with drivers, vehicles and supplies, and even transported soldiers on its chartered planes.

Bill Turner, then-CEO of Anvil Mining, admitted that the army “requested assistance from Anvil for transportation” and that his company “provided that transportation.”[2]

The Canadian general manager of Anvil’s Congo operations was prosecuted and cleared of charges in a trial that was widely condemned as an injustice by numerous organizations, including the UN.

Meanwhile, both the Québec Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court of Canada refused to hear the case and said that survivors needed to sue the company in Congo or Australia, despite the fact that Anvil was headquartered in Montréal and its largest shareholders were Vancouver-based mining company First Quantum Minerals and the Canadian Pension Plan.

In response to the ruling, Matt Eisenbrandt of the Canadian Association Against Impunity stated,

“It is unacceptable that…victims are still unable to hold Canadian companies accountable in Canadian courts, for their alleged involvement in serious human rights violations committed abroad. We look forward to a time when Canadian companies are held responsible for their actions.”

Adèle Mwayuma, whose two sons were killed during the Kilwa massacre, stated that Canada’s refusal to hear the case was “another rebuff for the families who have suffered so much and struggled so long to have this case heard.”[3]

The Canadian government’s refusal to hold Canada-based companies responsible for their abuses abroad is part and parcel of the mechanisms by which Canadian imperialism operates.

In Congo specifically, Canada has historically cooperated with more forceful imperialist powers, including the United States, to create an investment climate that is friendly to multinational business.

In Western media, much has been made of China’s increasing investment in critical Congolese minerals, a trend which the Biden administration has identified as a “U.S. supply chain concern”—however, to focus simply on China’s ownership of mineral resources in the region would belie the reality that, in relation to its size, Canadian mining capital has historically held far more weight in Africa.[4]

The DRC is the tenth largest recipient of Canadian development aid, a fact that the Government of Canada proudly proclaims on its webpage for Canada-DRC relations.[5] Congo is also the third most profitable African country for Canadian mining companies—a less publicized fact, and one which offers a window into Canada’s deeply exploitative role on the African continent, both historically and presently.

In the 2020-2021 fiscal year, Congo received CAN$121 million in Canadian aid, which the Government of Canada upholds as evidence that “Canada contributes to the development of the DRC.”

However, a glance at Canadian investment statistics reveals a yawning chasm between the amount of aid Canada sends to Congo and the amount of profit Canadian companies extract. Indeed, statistics from Natural Resources Canada note that Canadian mining assets in the DRC are worth $6.5 billion.[6] Total Canadian aid contributions from 2020-2021 are less than 2% of that figure.

The grim truth is that the DRC, once led by a fierce champion of anti-colonialism in Patrice Lumumba, has effectively been recolonized by Western capital. Canada, which haughtily proclaims its global munificence, was not an innocent bystander in this process—in fact, individual Canadians and the Canadian state itself played a notable role in supporting the Belgian colonization of Congo, perpetuating the colonial system, and working alongside Belgium and the U.S. to destroy Lumumba’s vision for an independent, decolonized, pan-Africanist Congo.

Canadian companies and government officials have also been implicated in the continuation of the resource conflicts in the country’s east that erupted after the fall of Mobutu Sese Seko in the late 1990s.

When King Leopold II, the execrable Belgian ruler who began the genocidal colonization of the Congo, established the “Congo Free State” in 1884, the U.S. administration of Grover Cleveland was the first government in the world to recognize him as the area’s sovereign ruler.

Following American recognition, the European powers acquiesced to Leopold’s personal rule of the territory at the Berlin Conference of 1885 and, thereafter, the Belgian king began to put more time into mapping the region’s land and resources and repressing local resistance.

Many are not aware that Leopold employed a Canadian, William Grant Stairs, to help him spread Belgian control across the region. In 1891, Leopold sent Stairs, a graduate of the Royal Military College of Canada and a well-to-do Haligonian whose family accrued part of its wealth by selling food and construction materials to Caribbean slave plantations, to conquer the mineral-rich Katanga region of the Congo. In his diary, Stairs wrote that his goal was to “discover mines in Katanga that can be exploited” and to make Msiri, the region’s ruler, “submit to the authorities of the Congo Free State, either by persuasion or by force.”[7] He led an army of 2,000 men to accomplish this task.

While traversing the territory, the Stairs expedition was known to flaunt the severed heads of Africans as a “lesson” to locals. Yves Engler writes that “there are disturbing claims that some white officers took sex slaves and in one alarming instance even paid to have an 11-year-old girl cooked and eaten.”[8] Ultimately, the expeditioners killed Msiri, the chief of Congo’s Yeke kingdom, cut off his head, and stuck it on a pole as a “warning” to his people.

When Stairs and his men returned Msiri’s body to be buried, the ruler’s head was not included. To this day, the people of Congo do not know what became of Msiri’s head, but they do know one thing: The Canadians came to their land to pillage, kill and enslave.

By the expedition’s end, Stairs and his men had added 150,000 square kilometers to King Leopold’s “Congo Free State.”

In June 1892, Stairs died of malaria while in the Congo. He was promptly lionized by the Canadian government, which placed two brass plaques in his name at the Royal Military College. One of the plaques praises Stairs’s “courage and devotion to duty” and notes that he “died of fever…whilst in command of the Katanga Expedition sent out by the King of the Belgians.”[9]

Some sources attest that half of the Congo’s population—more than 10 million people—died under the Belgian king’s tyranny. Torture and maiming were institutionalized practices.

The colonial police force, the Force Publique, imposed strict rubber extraction quotas on enslaved Africans and, when an African failed to meet the quota, officers were instructed to cut off a hand as punishment.

In addition to corpses, baskets of severed hands littered the Congo Free State, a putrid emblem of the brutality of Belgium’s colonial rule. And although the Belgian government annexed the Congo in 1908 due to supposed humanitarian concerns, conditions did not notably improve thereafter.

By the early 20th century, numerous American companies had expressed interest in the Belgian Congo. J.P. Morgan met with Leopold in Dover, while Thomas Fortune Ryan and John D. Rockefeller, Jr., visited the king in Brussels. The American Congo Company, owned by Ryan and Daniel Guggenheim, were granted a 99-year concession of 4,000 square miles from which to harvest rubber and vegetable products, a concession they ultimately traded for nearby mining rights.

American investors also joined Belgian financiers (and King Leopold himself) to back the creation of Forminière, a mining company which acquired a 99-year monopoly on mining rights in an area covering about half of the Congo Free State.

A December 1906 exposé published by William Randolph Hearst’s New York American identified several towering figures of U.S. capitalism as having financial interests in the Congo Free State:

“Thomas Fortune Ryan, James D. Stillman, Edward B. Aldrich (son of Nelson W. Aldrich, Republican leader in the Senate, and brother of Winthrop W. Aldrich, Mr. Eisenhower’s ambassador to the Court of St. James’s), the Guggenheim brothers, J. P. Morgan, and John D. Rockefeller, Jr.”[10]

Canada sought to invest in the Belgian Congo as well. Indeed, Kevin A. Spooner writes that “the Belgian Congo was served relatively well by Canadian officials.” In 1946, the Congo was the site of one of only three Canadian trade commissions in Africa, and Canada remained a “top twelve trading partner” until the early 1950s. Canadian officials were primarily interested in the minerals in the country’s east.

“As early as the 1920s,” writes Spooner, “the Canadian trade commissioner in South Africa, G.R. Stevens, had gathered information on opportunities for Canadian trade in the Congo. In his report, Stevens noted the importance of minerals in the eastern Katanga province, which the Canadian William Grant Stairs had helped bring under Belgian control thirty years prior.”[11]

Throughout the 20th century, the merciless European empires continued to relegate Africans to the status of colonized peoples across the continent, extracting profit through repressive systems of forced labor and answering any resistance with violence. While in Washington opinions about the continuance of colonialism occasionally differed, Ottawa supported the system completely.

A number of Canadian companies had a material investment in its perpetuation. Between 1950 and 1965, the Canadian government allocated millions of dollars to private contractors for the purpose of resource surveys, including geological surveys, in Nigeria, Tanzania, Uganda, and across West Africa.[12] By 1960, Canadian businesses had invested almost $70 million in Africa.[13]

As a result, the Canadian government maintained strong relationships with the colonial administrations, particularly those of Britain, and did not make any official diplomatic contact with indigenous Africans. By the mid-twentieth century “Ottawa had neither made any public utterances condemning British colonial policy [in Africa] nor had it requested the speeding up of the giving of independence to members of the Commonwealth.”[14]

Alongside the U.S., Ottawa gave military assistance to the empires which were seeking to quash the independence aspirations of Africans. Between 1950 and 1958, Canada donated approximately $1.5 billion ($8 billion today) to fellow NATO nations through the organization’s Mutual Aid fund.[15]

Three-quarters of Canadian Mutual Aid was military, including “anti-aircraft guns, military transport vehicles, ammunition, minesweepers, communications and electronic equipment, armaments, engines, and fighter jets.”[16]

The largest recipients of Canadian arms and equipment were France (which was attempting to suppress anti-colonial movements in North Africa and Indochina), Britain (which had launched a similar campaign in Malaya), the Netherlands (Indonesia and West Papua New Guinea), Portugal (Angola, Mozambique and Guinea-Bissau), and, most relevant to this article, Belgium (Rwanda, Burundi and Congo).

The Canadian military also ran training programs, such as the NATO Air Training Plan, in which the Royal Canadian Air Force trained approximately 5,500 pilots and navigators from ten NATO countries, including Belgium.

In the late 1960s, the Canadian government donated $25.5 million to the British-led Special Commonwealth Africa Assistance Program (SCAAP). The overall purpose of the SCAAP was to ensure that capitalist structures remained in Africa as countries gained their independence, and that Canadian business retained lucrative investment opportunities within those structures.

Secretary of State for External Affairs Sidney Smith stated that, without a Canadian presence in Africa, “these underdeveloped [African] countries…may be prone to accept blandishments and offers from other parts of the world”—implicitly, communist parts of the world.[17]

Patrice Lumumba was the first prime minister of the Democratic Republic of Congo following the Congolese peoples’ victory over Belgian colonial rule. He was detested by leading U.S. and Canadian officials.

While UN officials were open in their scorn for Lumumba’s independent domestic and foreign policy—UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld asserted that he must be “broken,” while his special representative Andrew Cordier said “Lumumba is [Africa’s] little Hitler”—Canadian Prime Minister John Diefenbaker kept his distaste close to the vest. He privately referred to Lumumba as a “major threat to Western interests” and joined other Western nations in supporting a separatist movement in the Katanga province to destabilize the Congolese leader’s fledgling administration.[18]

In August 1960, U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower ordered the CIA to “eliminate” Lumumba. Pursuant to this task, the Agency sent a kit of various poisons, including a tube of poisoned toothpaste, to the CIA station chief in Léopoldville (now Kinshasa), Lawrence Devlin, alongside orders to kill the prime minster.

Ultimately, Lumumba was not poisoned. In 1961, he was murdered by Katanga separatists who were working with Belgian and American intelligence forces. The brutality of this killing is widely understood; less known is the fact that a Canadian peacekeeper has claimed responsibility for delivering Lumumba to his killers. Québec native Jean Berthiaume, chief of staff of the UN peacekeeping force, says that he located Lumumba after the leader’s escape from house arrest and informed army chief Joseph Mobutu of his whereabouts. “I called Mobutu,” the Canadian peacekeeper recalled decades later

“I said, ‘Colonel, you have a problem, you were trying to retrieve your prisoner, Mr. Lumumba. I know where he is, and I know where he will be tomorrow.’ He said, ‘what do I do?’…it’s simple, you take a Dakota [plane], send your paratroopers and arrest Lumumba in that small village…That’s all you’ll need to do, Colonel. He arrested him, like that, and I never regretted it.”[19]

After his arrest, Lumumba was held in starvation conditions in a military prison in Thysville (now Mbanza-Ngungu). Fearful that he would continue to inspire popular resistance among the Congolese people, the Belgians had him flown to Katanga. On the flight, he and his associates were beaten nearly to death by Katangese and Belgian soldiers.

Upon landing, they were executed by firing squad. In order to prevent his place of death from becoming a site of national remembrance, Belgian officers dismembered his corpse and dissolved its pieces in sulfuric acid.

After Lumumba’s murder in January 1961, Canadian officials jumped at the chance to ingratiate themselves with the Mobutu regime. In 1992, Canadian diplomat Michel Gauvin recalled,

“During my time in Leopoldville as Chargé d’Affaires [from 1961 to 1963] I got to know Mobutu very well. I was one of the only whites invited to the baptism of one of his girls.”[20]

Historian Fred Gaffen explains that

“Mobutu learned to trust the Canadian officers [and] visited Canada in May of 1964. At that time, he thanked those Canadian officers who had contributed so much to the maintenance of the unity of the country.”[21]

The transition from Lumumba to Mobutu, however, was not a smooth one. Following Lumumba’s killing, a group of anti-imperialist “Lumumbist” rebels took up arms in the eastern Simba region, intending to resist the new U.S.-backed Moïse Tshombe administration.

The U.S. government provided T-6 Texan airplanes to the Tshombe government, trained Congolese pilots, and ran several combat missions against the Lumumbists in the east. Tshombe also employed white mercenaries to fight the resistance forces, including Irishman “Mad Mike” Hoare and a Belgian plantation owner and white supremacist named Jean Schramme. By the end of 1964, the Lumumbist resistance was defeated.

Ultimately, the U.S. decided that Tshombe was an ineffectual leader and supported his ouster.

Joseph Mobutu, the Army Chief of Staff who had helped organize Lumumba’s overthrow, took power, renaming himself Mobutu Sese Seko and renaming his country Zaire. To solidify his rule, Mobutu isolated the white mercenaries who had previously been a key element of Tshombe’s anti-Lumumbist offensive in the east.

Some of the mercenaries, including plantation owner Jean Schramme, revolted. When it became clear that Schramme and his mercenaries would not be able to restore Tshombe to power, they consented to leave the country in an International Red Cross airlift. Canada agreed to assist in the transportation of 900 Schramme supporters in an operation dubbed “PELI PELI.”

Western nations—primarily the U.S. and France—kept Mobutu in power for more than three decades. His regime was one of the most notoriously corrupt in history.

The U.S. contributed more than one billion dollars in civilian and military aid during Mobutu’s 30 years in Kinshasa, while the French were even more generous.

“For [their] heavy investment,” Adam Hochschild writes, “[they] got a regime that was reliably anti-Communist and a secure staging area for CIA and French military operations, but Mobutu brought his country little except a change of name, in 1971, to Zaire.”[22]

In 1997, his personal wealth was estimated at $4 billion, making him one of the richest men in the world. That same year, a UN Conference on Trade and Development report revealed that the overwhelming percentage of Congo’s population did not have access to safe drinking water,

Twelve percent of infants died at birth, and state health expenditures were less than 1% of total GDP. Congo was also the world’s most “severely indebted LDC.”[23] However, despite his willingness to adopt Western-backed “structural adjustment” policies, Mobutu kept most of Congo’s mining industry under state management through the Societe Generate des Carrieres et des Mines (Gecamines) and the Societe Miniere du Bakwanga (MIBA).

In addition to producing huge amounts of gold, copper, diamonds and uranium, Congo is also the world’s largest producer of cobalt, producing more than half of the global supply. Cobalt is a central component in cell phones and other consumer electronics which, by the late 1990s, were becoming an increasingly profitable industry.

Mobutu’s control over reserves of cobalt and other mined goods “never ceased to irritate the great transnational mining corporations,” and toward the end of his time in power, he began to negotiate investment terms.[24] Many of the companies that entered negotiations were Canadian. They included Lundin Group, Banro, Mindev, South Atlantic Resources, Anvil Mining and Barrick Gold.

Mobutu’s caginess around Congo’s mineral wealth irked Canada and the U.S., and it contributed to their gradual abandonment of their once-beloved dictator. In the 1980s, Canada had channeled more than CAN$140 million to Mobutu through its international aid agencies (it is estimated that CAN$16 million went directly to the regime) but, between 1989 and 1994, aid numbers shrank to one-thirtieth of their previous size.[25]

Having identified Mobutu as an obstacle to the further exploitation of Congo’s resource wealth, Canada and the U.S. chose a new ally in Laurent-Désiré Kabila, the leader of an armed rebellion in the east called the Alliance des Forces Democratiques pour la Liberation du Congo (AFDL). The AFDL was also backed by neighboring Rwanda and Uganda, two additional outposts of U.S. power.

While the AFDL marched toward Kinshasa to oust Mobutu, it took the time to map the immense wealth of the east—in fact, its route to the capital perfectly matched maps of the region’s mineral reserves. Even before Kabila reached the capital, numerous companies had signed contracts with him for massive swaths of Congolese land. This time, the Europeans were frozen out—it was primarily Canadian and U.S. companies fueling the crisis in Congo.

In April 1997, a Washington Post article reported that

“American companies are leading the race into rebel-held areas of Zaire to exploit the country’s mineral wealth…a major shift after years of European domination in Africa’s largest French-speaking country.”

The author, Cindy Shiner, noted that

“miners, bankers, lawyers and communications companies have been courting the rebel alliance led by Laurent Kabila, a former Marxist who has embraced free-market reform and pledges to overthrow the corrupt government of President Mobutu Sese Seko.”[26]

America Mineral Fields Inc., a U.S. mining company based in then-President Bill Clinton’s hometown of Hope, Arkansas, signed a $1 billion contract with the rebels to explore copper and cobalt deposits in the country’s south. A subsidiary of the company, America Diamond Buyers, was the first foreign firm to sign a contract with Kabila’s forces.

Meanwhile, the Washington-based New Millenium Investment Ltd. opened the first bank in the rebel stronghold of Goma and signed a contract to “revitalize Goma’s telecommunications.” COMSAT and Citibank also “expressed interest in the region.”[27]

On the Canadian side, the three largest companies in Congo were Adastra (the new name for America Mineral Fields Inc.), First Quantum Minerals, and Barrick Gold. These companies were so eager to tap unexploited reserves that they signed contracts for land that had not yet been claimed by Kabila’s forces, and even provided equipment to his men as they pushed toward Kinshasa. In 1997, Kabila visited Toronto to speak to Canadian mining companies about “investment opportunities,” a trip that “may have raised as much as $50 million to support [his] march on the capital.”[28]

The Wall Street Journal reported that

“American, Canadian and South African mining companies are negotiating deals with the rebels controlling eastern Zaire. These companies hope to take advantage of the turmoil and win a piece of what is widely considered Africa’s richest geological prize.”[29]

Former Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, former U.S. President George H.W. Bush and former CIA Director Richard Helms were on Barrick Gold’s board during this period, while Vancouver-based First Quantum Minerals hired former Prime Minister Joe Clark to serve as their special adviser on Africa as well as their representative to Kabila.

Clark soon became part of what The Christian Science Monitor called Kabila’s “circle of Canadian advisers.”[30] The stock prices of all the above-listed companies rose considerably as Kabila barreled toward, and finally captured, Kinshasa in 2001.

Speaking in his capacity as First Quantum’s Africa specialist, Joe Clark said that

“the government of Congo knows that if it’s going to make progress quickly in terms of using assets that create jobs, mining is more likely to do it than other sectors.”[31]

Meanwhile, the UN Security Council condemned the illegal exploitation of Congolese resources and stated, in the plainest possible terms, the role that mineral extraction played in the country’s conflicts:

“The Government of the DRC has relied on its minerals and mining industries to finance the war…Bilateral and multilateral donors and certain neighboring and distant countries have passively facilitated the exploitation of the resources of the DRC, and thereby the continuation of the conflict.”[32]

In September 2009, Canada and the Congolese government clashed once more. That month, new president Joseph Kabila, a man of murky origins alleged to be the son of AFDL leader and U.S.-Canadian ally Laurent-Désiré Kabila but believed by some Congolese to be an impostor named Hyppolite Kanambe, withdrew First Quantum’s rights to a copper mine in Congo’s east.

Stephen Harper’s Conservative government immediately released a statement calling on Kabila (Kanambe) to “enhance governance and accountability in the extractive sector.”

Later, the Financial Post reported that

“Harper will raise the case of Vancouver-based First Quantum Minerals Ltd. with representatives from the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and other governments that do business with the DRC.”

The Congolese information minister called Canada’s response “unacceptable,” but Harper continued to apply pressure, threatening to prevent a much-needed restructuring of debt accrued during the Mobutu dictatorship.[33]

Ultimately, Ottawa backed off when the Kabila government gave concessions to First Quantum. Canada’s aggressive response becomes even more shameful when one learns that, of the $41 billion produced by the Congolese mining industry between 2007 and 2012, less than 3% went into the country’s national budget.[34]

Canadian investments in Africa grew steadily during the Harper and Trudeau years. No longer is Canadian interest concentrated in South and Central Africa—significant investments spread through West Africa when exploration missions discovered massive gold reserves in the region.

Now, Canadian companies own more than half the gold mines in Burkina Faso with assets valued at over $2.5 billion.[35] They also own many of the most profitable mines in neighboring countries, including Loulo Gounkoto (80% owned by Barrick Gold) and Fekola (90% owned by B2Gold), both in Mali.

The Canadian state currently has its eyes on recently discovered mineral reserves in East Africa as well. In April 2016, Global Affairs Canada allocated $15 million in aid to Ethiopia to “improve policies, practices, and capacity to attract more interest and investment in the [mining] sector.”[36]

By 2020, Ethiopia had become the largest recipient of Canadian development aid, with a particular focus on “extractive sector development.”[37]

The U.S. and Canada have always aimed to undermine African sovereignty and facilitate resource exploitation by U.S. and Canadian companies generally, and Western companies more broadly.

While Canada is often omitted from analyses of Western imperialism, the country’s role in Congo has been very active and aggressive throughout history.

One can see evidence of this in the Canadian government’s support for the Stairs expedition and the Belgian colonial administration, in Ottawa’s clear distaste for Lumumba and his pan-Africanist principles, and in the state’s unwavering support for Canada-based companies accused of illegalities there, such as First Quantum and Anvil Mining.

And yet, in the minds of many people, Canada appears to be a gentle or downright benevolent presence on the world stage.

This is how Canadian imperialism functions.

The United States does the heavy lifting, but Canada provides consistent behind-the-scenes support and, as a result, its companies reap the rewards of the capitalist systems that its more overt imperialist partner imposes on these underdeveloped countries.

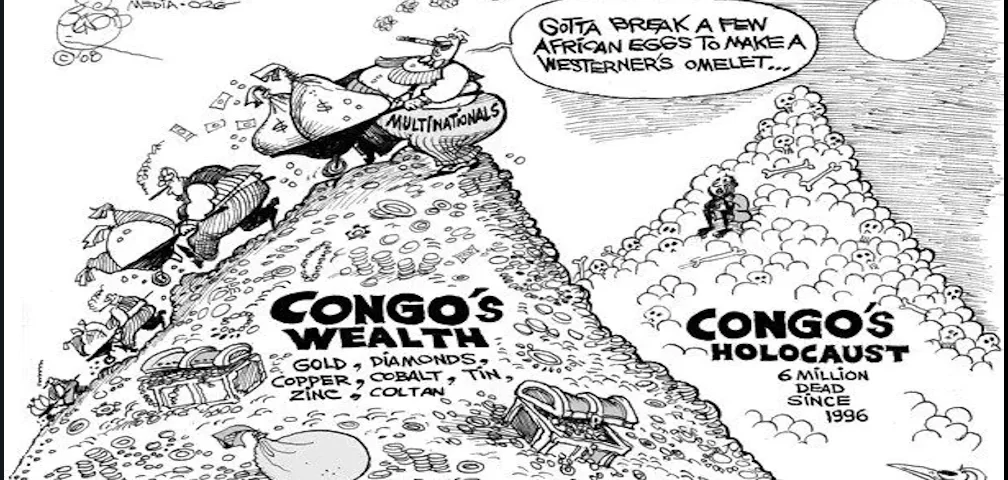

*Featured Image: Apologies to the artist, image slightly elongated and cropped to fit header.

- “Massacre in Kilwa facilitated by Anvil Mining, operating Dikulushi open pit, Katanga province, DR Congo,” Environmental Justice Atlas, https://ejatlas.org/conflict/kilwa-mine. ↑

- Quoted in Yves Engler, Canada in Africa: 300 years of aid and exploitation (Vancouver and Winnipeg: RED Publishing/Fernwood Publishing, 2015), 154. ↑

- Quoted in “No justice in Canada for Congolese massacre victims as Canada’s Supreme Court dismisses leave to appeal in case against Anvil Mining,” Global Witness, November 6, 2012, https://www.globalwitness.org/en/archive/no-justice-canada-congolese-massacre-victims-canadas-supreme-court-dismisses-leave-appeal/. ↑

- Congressional Research Service, “Democratic Republic of Congo: Background and U.S. Relations,” March 25, 2022, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/IF10216.pdf. ↑

- “Canada-the Democratic Republic of Congo relations,” Government of Canada, https://www.international.gc.ca/country-pays/democratic_republic_congo-republique_democratique_congo/relations.aspx?lang=eng. ↑

- “Canadian Mining Assets (CMAs), by Country and Region, 2019 and 2020 (p),” Natural Resources Canada, https://www.nrcan.gc.ca/maps-tools-and-publications/publications/minerals-mining-publications/canadian-mining-assets/canadian-mining-assets-cma-country-and-region-2018-and-2019/15406. ↑

- Quoted in Engler, Canada in Africa, 32. ↑

- Yves Engler, “William Grant Stairs of Halifax helped conquer the Congo,” Rabble, June 28, 2017, https://rabble.ca/anti-racism/canadian-who-helped-conquer-congo/. ↑

- Quoted in Engler, Canada in Africa, 33. ↑

- Robert Wuliger, “America’s Early Role in the Congo Tragedy,” The Nation, October 10, 2007, https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/americas-early-role-congo-tragedy/. ↑

- Kevin A. Spooner, Canada, the Congo Crisis, and UN Peacekeeping, 1960-64 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2010), 15-16. ↑

- Keith Spicer, A Samaritan State?: External Aid in Canada’s Foreign Policy (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1966), 154-155, 161. ↑

- Tyler Shipley, Canada in the World: Settler Capitalism and the Colonial Imagination (Halifax, NS: Fernwood Publishing, 2020), 255. ↑

- Chukwudi Pettson Onwumere, quoted in Engler, Canada in Africa, 10-11. ↑

- Engler, Canada in Africa, 91. ↑

- Engler, Canada in Africa, 91. ↑

- Quoted in Engler, Canada in Africa, 112. ↑

- Quoted in Engler, Canada in Africa, 120. ↑

- Quoted in Engler, Canada in Africa, 121. ↑

- Quoted in Engler, Canada in Africa, 122. ↑

- Quoted in Engler, Canada in Africa, 122. ↑

- Adam Hochschild, King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa (New York: First Mariner Books, 1999), 303. ↑

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, “The Least Developed Countries: 1997 Report,” https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/ldc1997_en.pdf. ↑

- Pierre Baracyetse, quoted in Delphine Abadie, “Canada and the geopolitics of mining interests: a case study of the Democratic Republic of Congo,” Review of African Political Economy 38, no. 128 (2011), 290. ↑

- Abadie, “Canada and the geopolitics of mining interests,” 290. ↑

- Cindy Shiner, “U.S. Firms Stake Claims In Zaire’s War,” The Washington Post, April 17, 1997, https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/inatl/africa/april/17/usstake.htm. ↑

- Shiner, “U.S. Firms Stake Claims.” ↑

- Quoted in Asad Ismi, “October 2001: The Western Heart of Darkness,” Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, October 1, 2001, https://www.policyalternatives.ca/publications/monitor/october-2001-western-heart-darkness. ↑

- Robert Block, “Mining Firms Want a Piece of Zaire’s Vast Mineral Wealth,” The Wall Street Journal, April 14, 1997. Quoted in Engler, Canada in Africa, 209. ↑

- Engler, Canada in Africa, 210. ↑

- Quoted in Ismi, “October 2001,” Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. ↑

- Security Council, “Security Council Condemns Illegal Exploitation of Democratic Republic of Congo’s Natural Resources,” United Nations, May 3, 2001, https://www.un.org/press/en/2001/sc7057.doc.htm. ↑

- Quoted in Engler, Canada in Africa, 215. ↑

- Engler, Canada in Africa, 156. ↑

- Owen Schalk, “Canadian imperialism and the underdevelopment of Burkina Faso,” Canadian Dimension, 28 Jul 2021, https://canadiandimension.com/articles/view/canadian-imperialism-and-the-underdevelopment-of-burkina-faso. ↑

- “Supporting the Ministry of Mines (SUMM) Ethiopia,” Canadian International Resources and Development Institute, 2021, https://cirdi.ca/project/supporting-the-ministry-of-mines-summ-ethiopia/. ↑

- “Evaluation of International Assistance Programming in Ethiopia 2013-14 to 2019-20,” Government of Canada, January 2021, https://www.international.gc.ca/gac-amc/publications/evaluation/2021/evaluation-ethiopia.aspx?lang=eng. ↑