by James Patrick Jordan, published on Popular Resistance, June 15, 2022

This article was originally published on the Alliance for Global Justice Website on June 14. Since then, left leaning candidate Gustavo Petro and Vice Presidential candidate Francia Marquez won the presidential election. This is a big moment for Colombia, which has been dominated by the U.S. and ruled by right wing presidents for a century. [jb]

I once asked a prominent social movement leader and former Colombian Senator if there was any organization or movement in her country similar to the US groups Veterans for Peace or Iraqi Veterans Against the War (now About Face). It was in 2011, and I was there with a delegation sponsored by the Alliance for Global Justice and the National Lawyers Guild. She looked at me a moment and then said, “We have veterans, but they are not for peace.” Her answer confirmed my own limited experience.

Of course, this was Colombia in 2011, a country that had recently learned about the “false positive” scandal, with details still being revealed. That scandal refers to the ongoing practice of members of the Colombian Armed Forces to lure poor and unemployed youth to remote areas with promises of jobs, killing them, and dressing their bodies in uniforms of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia-People’s Army (FARC-EP) and claiming them as enemy combatants. This was done to inflate numbers of the dead and reap rewards and promotions for their “successes”. The Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP) court says that there were at least 6,400 such cases between 2002 and 2008, alone, although some studies put the figure as high as 10,000. The scandal resulted in the incarceration of six members of the army, the firing of 27 officers, and the resignation of the Army Commander Gen. Mario Montoya.

The objective reality in Colombia was, and is, that an active duty soldier or veteran who advocates for peace or simply refuses to participate in the abuses and murders that have become all too commonplace, is someone who puts their own life in danger. When US soldiers come home radicalized, fed up with fighting Empire’s wars and looking to work for peace, they do so thousands of miles from the front lines. But in Colombia the battlefields are at home, and the repercussions for those who speak out can be severe.

Nevertheless, I have thought about what the former Senator said many times over the years. While the percentages have vacillated, there has been broad support for the peace accord. I personally observed a 2013 march for peace in Colombia that had 1.2 million participants. Military service is compulsory in Colombia, although there are channels that young people can take to avoid it, especially if their families have economic resources. This means that a high proportion of soldiers are from poor, working class, and/or campesino families. Most of the young men and women entering the Colombian military do not go in as monsters, with murder on their minds.

But the pressure must be immense. Even as I write this, news comes in that soldiers responsible for the torture, mutilation, and murder of Dimar Torres are being released from captivity. Torres was killed on April 22, 2019. An article I wrote published by the Alliance for Global Justice describes what happened:

“Dimar Torres Arevalo was an ex-insurgent who had laid down his arms to be reincorporated into civil life. He was a resident of the village of Carrizal, in the Municipality of Convención, Department of Norte de Santander. Wilson had gone to the nearby village of Miraflores to buy a hunting knife. When village residents noticed he had not returned sometime later, they went to a nearby military checkpoint that has been in the area for years, asking after his whereabouts. Later, they heard gunshots and returned to find soldiers trying to bury Wilson’s corpse. The villagers surrounded the soldiers, began recording them, and took possession of the body, refusing to leave, even when the military began firing warning shots in the air. They demanded the presence of competent Colombian authorities and United Nations representatives. A later forensics report detailed a chilling succession of events. The murder had been committed by 5-8 soldiers, preceded by torture. First, he was beaten with rifles and sexually violated before his genitals were cut off. He was then further beaten and shot at point blank range.”

The situation is greatly complicated when the soldiers who commit such atrocities so frequently find themselves backed up by a legal and political system that overwhelmingly gives them impunity and a free hand, rather than consequences for their crimes.

Even so, I was sure there must have been examples of soldiers and of veterans who wanted peace, and who resisted abuses. Where were they, who were they, what were their stories? I couldn’t let these questions rest.

It was not long before I learned about of Raúl Antonio Carvajal Londoño, a young soldier who refused orders to kill civilians as part of the false positive scandal. His refusal costs him his own life, shot dead by his superior officers on October 8, 2006. The official cause for his death was that he was killed in battle by guerrillas. However, he was stationed in an area outside the conflict zones, in a place where no battle had taken place. For 14 years, his father, Raúl Carvajal (Sr.) had waged a campaign for justice for his son until he died from Covid-19 in June 2021.

In 2016, I got another glimpse of military attitudes and even was able to spend time in conversation with a few soldiers. I was traveling with my friend and comrade Dan Kovalik, a noted author and human and labor rights lawyer. We had traveled to the village of Cominera, a rural part of the municipality of Corinto in the north of the Department of Cauca. We were there to observe the October 2, 2016, plebiscite on the peace accords. We would find out later that the NO vote had won by just .5% in a vote marred by low voter turnout, a massive propaganda campaign of “fake news” by mostly protestant churches, and a hurricane that blasted the Caribbean area the day of the vote, an area that had the highest levels of support for the peace accord in the country.

The morning of the vote, we went to the polling place. As we arrived, a column of around 15 soldiers marched into the area. Most the soldiers were aloof, and a few looked visibly unhappy with our presence. A few, however, were friendly and appeared enthusiastic to see us. I particularly remember a couple of Afro-Colombian soldiers who wanted to talk and even have their pictures taken with us. They indicated that they were among the Colombians who sincerely hoped for peace and an end to the armed conflict. They almost seemed giddy with excitement.

Dan had brought a flag emblazoned with a peace sign and had asked the voting officials if he could raise it somewhere nearby, apart from the polling station. The two soldiers eagerly volunteered to help, and they were all smiles when they saw the flag waving. When I think about peace in Colombia, of course I think of the workers and the campesinos and the popular movement leaders and the ex-insurgents, what it means for these. But I also often think of these two young soldiers, that peace is good for them, too. A just peace in Colombia would be for everyone.

Right now, I am in Colombia, between the first and second (and final) votes for the country’s next president. I am here reporting on the elections for the Alliance for Global Justice, and we have also organized observation teams. More than a few times I have seen or heard analysis that describes the elections as having an existential impact on the fate of the 2016 peace accord. Could this vote decide the future of Colombia’s peace process?

Two votes have already occurred. On March 13, 2022, the Center-Left Pacto Historico (Historic Pact) won the largest block in the Senate and the second largest block in the House—but that win was ceded only after massive fraud was uncovered that had originally produced skewered returns. After the first round of the presidential vote on May 29, 2022, Gustavo Petro and Vice Presidential candidate Francia Marquez, won 40% of the vote, coming in first. However, Rodolfo Hernández, often called “Colombia’s Trump,” won 28%, and Right wing candidate Federico “Fico” Gutierrez picked up 24% of the vote. Allegedly “Centrist” candidate Sergio Fajardo only got 4% of the vote. Most had assumed that Gutierrez would challenge Petro in the run-off election. For Hernández to finish second was considered an upset.

Whatever the results from these first two votes may say about Colombian voters, one thing is clear: the status quo of Uribismo (the ultra-right, paramilitary-associated, political trend lead by former president and current senator Álvaro Uribe) and the rudderless “Center,” were both soundly rejected. Fico, the establishment candidate of the right, didn’t even break 25% of the vote, and the vote for Fajardo relegated him to irrelevancy.

That is what was rejected. But what was embraced? The March 13 results may have been positive for the Pacto Histórico, but beyond that, it is hard to predict. If Left and Centrist forces in the Congress can unite around legislation, they have a majority that could wield considerable power. However, that’s not a reality that can be counted on. For instance, the Liberal Party is the most powerful congressional block in terms of both their seats in the House and the Senate. The Liberals represent a certain side of Colombian economic power. Beyond that, they are unpredictable. This Party has produced both the Leftist Piedad Córdoba and the ultra-right Álvaro Uribe. The new Congress will wield tremendous influence in the coming years, even if it is by the leadership of the inept and incapable. If that is the case, they will likely lead Colombia into a quagmire. Whoever is elected president on June 19th, Congress could make or break them.

And who will that be? The latest polls show a statistical tie. While it’s all but impossible to predict who will win, we can examine what the election will mean for the peace process.

Gustavo Petro of the Pacto Histórico, is himself a product of a peace process. As a young member of the M-19 insurgency, his reincorporation into civil society and entry into political office was made possible because of the deal reached between the M-19 and the Colombian government. Similarly, Petro has not wavered in his support of the negotiations that began in 2012, nor of the 2016 peace accord that resulted.

Of course, no peace process in Colombia is truly complete as long as the country remains a military colony of the Pentagon and the US government. If Petro has given any indication about that, it is that he will not take major actions to reverse Colombia’s role as a crucial regional and world partner in the US/NATO Empire. The struggle for Colombia’s “second independence” will have to continue with or without a Petro presidency.

Populist and Rightist candidate Rodolfo Hernández has said he not only supports the peace deal, but that he would make it retroactive to include the ELN (Popular Liberation Army). However, Hernández does not have a history of advocacy for the peace process and, in fact, voted against it in the 2016 plebiscite.

Just as true peace in Colombia cannot be separated from its international, it also cannot be separated from the repression of social movements, and from the general conditions of poverty that continue to prevail in this country, the second most unequal country in the Americas. It is worth noting that the Colombia National Police, rather than a civilian force, are under the direction of the Colombian Armed Forces and the Minister of Defense (something Petro has proposed to end). It is not incorrect to say that the main targets of the Colombian Armed Forces in recent years have not been so much armed groups as unarmed protesters and social leaders. Hernández has proposed the creation of a giant mega-prison larger than the metropolitan area of Bogotá, where prisoners who do not work would not be fed. He is a supporter of the US co-created and funded ESMAD riot police, one of the most hated institutions in Colombia, responsible for casualties for popular movements both in rural and urban settings. Petro, on the other hand, has been the only major presidential campaign who joined the call to dismantle ESMAD. Generally, Hernández would be for expanding the power and strength of Colombia’s military and police.

On May 22nd, I was in the Plaza Bolívar in the center of downtown Bogotá to observe the final Petro/Marquez campaign rally before the first-round vote. The Plaza was a sea of flags and banners that mostly reflected the Left nature of the Center-Left coalition. I feel quite at home among red flags and posters of Ché, it is true. But I found myself wondering—does the Petro/Marquez ticket have support from the Center? And I began to muse again about that 2011 conversation with that former Senator, and the existence or non-existence of veterans for peace in the country. Whoever wins on June 19th, is there broad support to sustain the peace process?

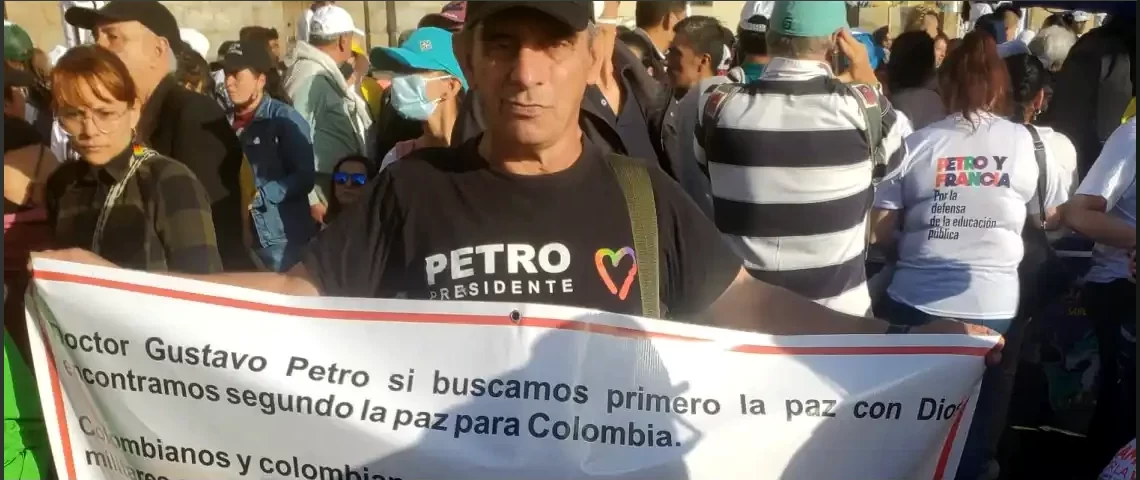

I looked to see a lone man standing with a rather large banner. What I read were not the words of another Red like me. They were the words of someone who truly hungered in his heart for peace, who had thrown his support behind Gustavo Petro. They were the words of a religious man. They were the words of a veteran:

“….Colombians, I am an ex-soldier from a family of ex-soldiers, and I fought the M-19 in the years ’80 and ’85 in Caquetá. The M-19 never involved itself in the recruitment of minors, much less involved itself in narco-trafficking. For this reason, I support Gustavo Petro and Francia Marquez and I have them in a prayer chain….

I remind you, ladies and gentlemen… [what] they [the Colombian establishment] want is to buy airplanes and weapons for war with what belongs to us. Colombia doesn’t matter to them, only silver and the spilling of innocent blood.”

There is another power in Colombia that is stronger even than the combined might of the presidency, Congress, and the Colombian oligarchy, backed up by the military might of the USA. It is the power of the people, a people fed up with war and repression, a people who want peace, a people made up of workers, students, campesinos, ex-insurgents…and, yes, even veterans for peace.

I think of the massive popular strikes of 2019 and 2021, movements that beat back austerity measures and directly resisted the machinery of repression and war.

My prediction? The dream of peace and justice for Colombia and the world will remain as long as it is held in the hearts of the people.