by Minnie Bruce Pratt, published on Workers World, February 9, 2022

Indigenous peoples regain redwoods forest lands on unceded land of the Onondaga Nation, Haudenosaunee Confederacy.

The growing LandBack movement by Indigenous nations won another significant victory Feb. 1, when more than 500 acres of the “Lost Coast” in California was transferred to the InterTribal Sinkyone Wilderness Council. (sinkyone.org)

The council is a “nonprofit consortium of 10 federally recognized Northern California Tribal Nations with cultural connections to the lands and waters of traditional Sinkyone, Cahto and neighboring Tribal territories.” The majority of members are Bands of the Pomo Indians. The Save the Redwoods League (STRL) worked with the consortium to finance and complete the transfer.

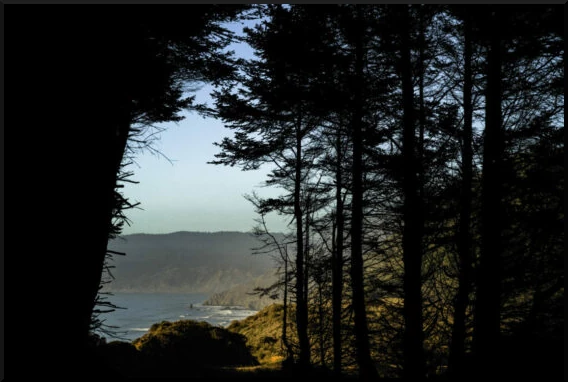

This area in northern California is home to endangered old-growth redwood trees, the tallest trees on Earth. That forest has now been renamed Tc’ih-Léh-Dûñ (Fish Run Place) in the Sinkyone language, to recognize Indigenous peoples who lived cooperatively in the region before being attacked and forced out by European and U.S. settlers. During colonization and then capitalist exploitation of the area, 95% of Pacific Coast redwood forests were logged and destroyed. (savetheredwoods.org)

Priscilla Hunter, chairwoman of the Sinkyone Council, said it’s fitting they will be caretakers of land where her people were removed or forced to flee before the forest was stripped for profit. “It’s a real blessing,” said Hunter, of the Coyote Valley Band of Pomo Indians. “It’s like a healing for our ancestors. This [land] was given to us to protect.” (CBS Sacramento, Jan. 25)

STRL president Sam Hodder said the group’s goal was to increase the range of land managed by Native communities, returning that to Indigenous knowledge and practices, such as prescribed fire: “These communities have been stewarding these lands across thousands of years. It was the exclusion of that stewardship that’s gotten us into the mess that we’re in.” (CBS Sacramento, Jan. 22)

PG&E fires linked to forest devastation

One environmental “mess” Hodder references is the dangerous fire conditions created by destruction of forest by megapower company Pacific Gas and Electric.

The same day the Tc’ih-Léh-Dûñ preservation was announced, PG&E was scheduled to exit five years of criminal probation. Its capitalist crime? A 2010 explosion triggered by its natural gas lines, which blew up a San Bruno neighborhood and killed eight people.

PG&E has refused to bury its dangerous lines that spark fires. Instead, the company has destroyed many large and old trees that could ignite on contact with the lines. This has further degraded the environment.

Since 2010 the company has been linked to more than 30 massive fires, destruction of over 23,000 homes and businesses, the direct deaths of more than 175 people and subsequent uncounted health emergencies of more people. The 2018 Camp Fire, California’s deadliest and most destructive, killed 85 people and displaced 90% of the people in the town of Paradise, destroying that and most of three other towns. (“The inferno industry and PG&E,” Workers World, Jan. 22)

Most of the Tc’ih-Léh-Dûñ area was bought by the STRL in 2020 from PG&E. The land is habitat for the federally endangered northern spotted owl and other endangered species, and the utility company sought a cover for its environmental crimes against people and the Earth.

LandBack movement accelerates

The Tc’ih-Léh-Dûñ transfer marks a step in the growing LandBack movement to return Indigenous homelands to the descendants of those who had lived there for millennia before European settlers arrived and seized the land.

The current #LandBack movement began in 2018, advanced by Aaron Tailfeathers, a member of the Kainai Tribe of the Blackfoot Confederacy of Canada. In 2020, spurred by protests at Mount Rushmore — a sacred Native site mutilated by the faces of U.S. presidents — the Indigenous organization NDN Collective drafted the LandBack Manifesto: “The Reclamation of Everything Stolen from the Original Peoples.” This covers land, language, ceremony, food, education, health, governance, medicine and kinship. (landback.org/manifesto/)

The LandBack demand is direct: “Give us the land back.” Getting the land back is an issue of both economics and sovereignty. Land gives Indigenous peoples a basis for self-governance and physical survival, a way to protect the environment and access clean water, cultivate language and traditions, hunt, fish or engage in farming, create well-paying jobs, build schools and sustainable housing and expand their lives as they choose to do.

The LandBack movement has achieved substantial victories in a short time, including the 2020 U.S. Supreme Court McGirt decision that reestablished certain rights of sovereignty associated with 19 million acres of land under governance of the Five Tribes in Eastern Oklahoma — the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek and Seminole Nations.

More than a hundred years of struggle culminated on Oct. 8, 2021, in LandBack to Tribal Nations in the state now called Utah. By presidential executive order, after a recent battle during three administrations, the Bears Ears National Monument was returned as ancestral homeland to the nations that all refer to the area by the same name — Hoon’Naqvut (Hopi), Shash Jaa’ (Navajo), Kwiyagatu Nukavachi (Ute) and Ansh An Lashokdiwe (Zuni) — Bears Ears. (sacredland.org)

Now Tc’ih-Léh-Dûñ — where the Eel River runs between steep hills of old- and second-growth redwoods — has returned to its peoples. Now — toward another #LandBack victory!

*Featured Image: Leaders of the Onondaga Nation Protesting in 2014

More on the Bears Ears struggle in articles by Stephanie Tromblay, Workers World, Sept. 12, 2019, and Dec. 19, 2017.