by Neil DeMause, published on FAIR, August 25, 2020

As a historic set of wildfires sweeps across California, sparked by lightning and stoked by record heat and drought resulting from climate change (Mercury News, 8/19/20; Scientific American, 4/3/20), many news outlets have drawn readers’ attention to an additional problem the state faces in fighting the fires: shortages of the prison labor that it normally relies on for firefighting crews.

The California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection — known as Cal Fire — “has roughly half as many inmate fire crews than it originally had to work during the most dangerous part of wildfire season,” thanks to prison quarantines and Covid-related early-release programs, reported CNBC (8/21/20), and “rotating out firefighters isn’t an easy option because there’s already a significant shortage of workers available.” Insider (8/20/20) wrote that “the coronavirus pandemic is creating a shortage of inmate fire crews to battle the wildfires,” noting that California has “relied on incarcerated firefighters as its primary ‘hand crews’ since the 1940s.” The New York Times (8/22/20) declared that losing inmate labor “has been the difference between having the manpower to save homes from wildfires — or not,” and that “hiring firefighters to replace them, especially given the difficult work involved, would challenge a state already strapped for cash.”

The California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection — known as Cal Fire — “has roughly half as many inmate fire crews than it originally had to work during the most dangerous part of wildfire season,” thanks to prison quarantines and Covid-related early-release programs, reported CNBC (8/21/20), and “rotating out firefighters isn’t an easy option because there’s already a significant shortage of workers available.” Insider (8/20/20) wrote that “the coronavirus pandemic is creating a shortage of inmate fire crews to battle the wildfires,” noting that California has “relied on incarcerated firefighters as its primary ‘hand crews’ since the 1940s.” The New York Times (8/22/20) declared that losing inmate labor “has been the difference between having the manpower to save homes from wildfires — or not,” and that “hiring firefighters to replace them, especially given the difficult work involved, would challenge a state already strapped for cash.”

It’s a gripping story, certainly, of a state unable to respond sufficiently to one disaster because of steps taken to ward off another. But the coverage all danced around a key problem with framing this as a labor shortage: There are plenty of workers available in a state with 2.5 million people currently unemployed — no doubt including many of the fire-trained inmate workers who were released early by Gov. Gavin Newsom in order to free them from the threat of getting sick in California’s Covid-ravaged prisons. The main difference: Unlike prison laborers, regular citizens have to be paid more than pittance wages.

In California, inmates at state prisons are allowed to apply to work at “conservation camps” for a base rate of $5.12 per day, plus an additional $1 an hour when out fighting fires. As the Sacramento Bee (7/4/20) reports, most are assigned to hand crews that typically perform “the critically important and dangerous job of using chainsaws and hand tools to cut firelines around properties and neighborhoods during wildfires.”

Inmate fire crews have been the norm in California since the 1940s (LA Times, 8/19/20), part of a long history of local governments using prison labor to perform vital public services. Pacific Standard (8/22/18) recounted the practice’s origins:

When Congress passed the 13th Amendment to the US Constitution in 1865, ending slavery, it left open a loophole: Involuntary servitude could continue as “punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.” This effectively legalized slavery among imprisoned populations, allowing former slaveholders in the South to implement a convict lease system, contracting prisoners out to private firms. Even abolitionists were willing to sign on, due to their reliance on prison labor. African-American inmates were “leased—literally, contracted out—to businessmen, planters, and corporations in one of the harshest and most exploitative labor systems known in American history,” writes Matthew Mancini in his book One Dies, Get Another: Convict Leasing in the American South.

Convict leasing was formally outlawed in 1941, but the principle of using inmate labor to save money continues to this day. The estimated cost savings to the state of California from inmate firefighting alone is as much as $100 million a year (Democracy Now!, 11/19/18).

And using workers who are paid only dollars a day drives down wages for the non-incarcerated as well. Factory owners have complained they can’t compete for government contracts against UNICOR (Vox, 9/7/15), the government-owned company that employs inmates for “everything from manufacturing extension cords to operating dairy farms to recycling electronics” (Wired, 5/19/20).

While California wildfire coverage gave a nod toward the “debate” around such practices, it generally limited any discussion to a side note before getting on to the main question of Won’t anyone think of the fires? The New York Times (8/22/20), for instance, reported that the inmate labor shortage has “highlighted the state’s dependence on prisoners in its firefighting force,” which “to critics,” it said, is “a cheap and exploitative salve.”

But most of the Times story focused on the experiences of inmate firefighters (“We took special pride in being able to actually save people’s homes”) and the value they provide, quoting a former corrections office at a fire camp as saying, “How do you justify releasing all these inmates in prime fire season with all these fires going on?” A spokesperson for Cal Fire followed, declaring inmate fire crews to be “absolutely imperative to our ability to create hand line and do arduous work on our fires.” No prison labor advocates were cited, with the only “critic” a single firefighter union leader who complained that the state has been illegally expanding the inmate work program.

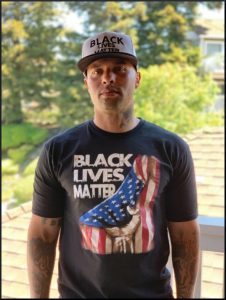

One expert critic they might have consulted is Rasheed Lockheart, a formerly incarcerated California resident who for the last two years before his release from San Quentin Prison worked for the San Quentin Fire Department as a lead engineer on a fire engine, and as the lead on an ambulance crew. Lockheart, who works with Planting Justice, a group that promotes food justice for people transitioning from prison, says using incarcerated workers to fight fires isn’t the problem — it’s not paying them a decent wage to do so.

“I don’t want to abolish the fire camps,” says Lockheart. But, he says, if prisoners are putting their lives on the line alongside fellow firefighters, “we should get equal pay, we shouldn’t be making a dollar an hour — I mean, there’s jobs inside the prison that get paid more than they get paid to be out there risking their lives.”

And when push came to shove, California was willing to pay to hire firefighters. A Cal Fire spokesperson tells FAIR that the department has recently hired more than 800 seasonal workers, nearly making up for the roughly 1,000 inmates who are missing from the normal complement. But while this might seem to present an easy solution — just hire back the recently released inmates who are already trained in firefighting — Lockheart explains that there’s another obstacle that makes this unlikely.

“I’m a city firefighter — my experience is mostly with municipal firefighting,” says Lockheart:

The problem with that is, in order to do that, you must have EMT certifications. But with a felony on our records, we can’t get EMT certifications. And with the wildland firefighting crews, with certain felonies, a lot of departments won’t take guys on. There are ways to get in, but it’s hard and it’s a long road.

Trained firefighters being good enough to work for nearly nothing, but ineligible to get real jobs, would seem to represent an even bigger irony — and a more important story — than California having to spend a few million dollars extra to fight two crises at once. But covering the wildfire story that way would require seeing it through the eyes of inmates, not of a government whose main concern is the inconvenience of having to pay people when you’re used to getting their work almost for free. That’s an argument we’ve heard before, of course — but one would have hoped it wouldn’t still be guiding news coverage nearly 200 years later.