by Qassem Muaddi, published on Mondoweiss, June 18, 2025

For three days, I was trapped in an area between three villages, no more than a ten-minute drive apart. At the entrance to each of the three villages, an actual iron gate blocked the road, quite literally caging in their residents. This was how Palestinians in the West Bank were informed of the new war that Israel started with Iran.

As soon as Israel launched its unprecedented attack, igniting the ongoing war between the two states, media attention shifted immediately away from the ongoing genocide in Gaza and the continuous Israeli offensive against Palestinians in the West Bank.

It was a Friday when Israel started the war, the day when travel within the West Bank is at its lowest, yet the effects of the Israeli lockdown on the West Bank were felt immediately: the Israeli army announced that the West Bank had been declared a closed military area, and checkpoints separating the West Bank from Jerusalem were closed, even for those Palestinians who have crossing permits. The Allenby border crossing with Jordan — the only way out of the country for West Bank Palestinians — was also shut in both directions.

Suddenly, the lockdown on the West Bank made it clear what we knew Israel has been silently doing to the West Bank over the past several years: it has turned Palestinian population centers into a network of connected “cages,” which Israel is able to open and shut whenever it wants.

Israel illustrated its utter control over the territory with its escalating war on Iran, closing almost all checkpoints between West Bank cities and villages, including hundreds of its 900 checkpoints, iron gates, and roadblocks.

In effect, they function as cages, like the three villages I was stuck in when the war started. This means that we can’t access work, hospitals, or anything in the city center — in the case of my village, that happens to be Ramallah. This changed slightly on Monday, four days into the war between Israel and Iran, when the gate at the northern end of my “cage,” separating the three neighboring villages from the rest of the road to Ramallah, was finally opened with occasional searches.

But on the southern end of the three-village cage, the gate remained closed. It separates my village from the Allon road, an Israeli-built street used by Israeli settlers. This road, and countless other Israeli roads that cut through the West Bank, are all part of Israel’s plan to effectively annex the West Bank while hiding the existence of Palestinians from view.

The ‘security’ roads meant for annexation

The Allon road runs through the West Bank from north to south along the eastern edges of the central hills of Nablus and Ramallah. Built by Israel in the 1970s with the pretext of keeping the Jordan Valley under tight Israeli military control “for security reasons,” the Allon road separates Nablus and Ramallah from the Jordan Valley, marking the border where Israel has since banned any Palestinian urban expansion. Israel has built dozens of illegal settlements along that road. In 2019, when Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu pledged to annex the Jordan Valley, he showed a map of the area slated for annexation, and it was none other than a repeat of the Allon Plan of the late 1960s.

The brainchild of Israeli politician Yigal Allon, the Allon Plan proposed to annex large swathes of the West Bank to Israel proper under the pretext of fighting security threats coming from the east. At the time, this was represented by the Palestinian fedayeen, who launched guerrilla attacks across the Jordanian border, but they were driven out of Jordan in 1970, well before the larger part of the Allon plan was implemented.

Following the Oslo Accords in the 1990s, Israel multiplied the construction of Israeli-only roads (dubbed “bypass roads,” since they bypassed Palestinian villages and towns and connected Israeli settlements to one another). Israel began creating a system where two nations existed in the same space: Palestinian native towns, villages, and cities, with their old network of roads, and new Israeli settlements with their own separate infrastructure. This was the basis for what the world later began to recognize as an Apartheid system in the West Bank.

But some roads were just too difficult to replace or split. To this day, Palestinians continue to be allowed to drive on parts of the Allon road, or other roads like Road-1, which links the West Bank’s northern and southern parts and passes by the Maale Adumim settlement east of Jerusalem.

But Israel has never had enough of segregating Palestinians, and it has never run out of “security concerns” either.

Before October 2023, the Israeli government had been allocating millions of shekels in infrastructure projects in the West Bank aimed at completely separating Israeli settlers from Palestinians on highways. Israeli Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich, who has been given extensive powers over the West Bank, has always defended these projects as a security necessity, pointing to individual Palestinian shooting attacks on Israeli settlers or soldiers. But Israeli leaders occasionally admitted that their West Bank agenda was much more than security.

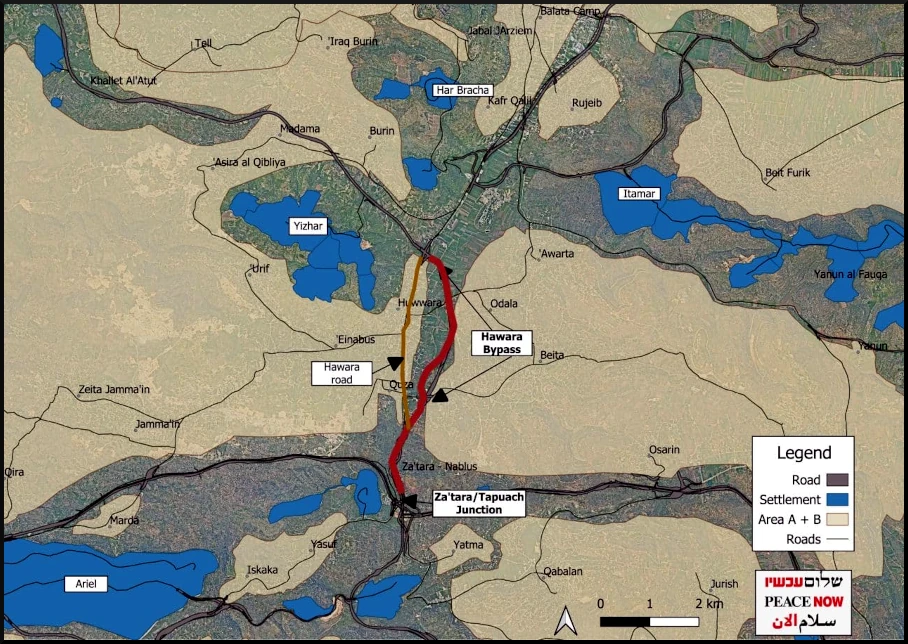

In February 2022, hundreds of Israeli settlers rampaged through the Palestinian town of Huwwara, south of Nablus, after a Palestinian fatally shot two Israeli settlers in the center of the town. Huwwara was one of the places where Palestinian and Israeli circulation had never been split, and Israeli settlers in the past had taken to shopping in the town due to its cheaper prices. Immediately after the settler pogrom, Smotrich stated that Huwwara had to be “wiped out,” and that it was the Israeli army — not the settlers — who should do it.

Shortly after, the Israeli army accelerated the building of a road parallel to the one coming out of Nablus, in order to connect it to the Allon road and prevent Israelis from crossing through Huwwara.

The project is massive, and it connects Israeli settlements east and west of the current road, facilitating the movement of Israeli settlers between the settlements south of Nablus. But it does much more than that: it separates Palestinian villages from their lands on the other side of the road — not annexing them officially, but making them inaccessible to their Palestinian owners.

Jamal Jumaa, coordinator of the Palestinian grassroots Stop The Wall campaign, told Mondoweiss that “the new road south of Nablus falls perfectly in place with previous Israeli plans drafted since the early 1990s, and it connects with other similar projects in the same area and beyond it in the West Bank.”

“The road in question connects with another road that the Israeli army is building further to the south, which includes a large bus station for all Israeli settlements in the Nablus and Ramallah areas to connect them to Jerusalem,” Jumaa clarified. “Israel is building the infrastructure of a state on Palestinian land.”

A similar project is being built in the south, from the Naqab desert through Masafer Yatta in the south Hebron Hills, Jumaa says. It reaches the southeastern edge of the Jerusalem desert. And yet another is the so-called “Fabric of Life” road, Jumaa adds, which intends to ban Palestinian vehicles from access to Road-1 and prevent them from maintaining a presence in the area east of Jerusalem in the heart of the West Bank. “All these projects connect with the larger network of Israeli infrastructure. They’re connecting settlements with each other and the settlements with Israel proper,” Jumaa explained.

“Simultaneously, these infrastructure projects isolate the Palestinian population in limited areas, with underdeveloped infrastructure, basically caging them in towns and villages under the full control of the Israeli army,” he added.

Tightening the cage

After October 2023, the Israeli army imposed a full closure of roads in the West Bank, with checkpoints that had been completely open for several years suddenly being completely closed. Israeli forces began to ease their restrictions on Palestinian movement in February 2024, maintaining the daily routine of the on-and-off closure of checkpoints.

But last January, immediately after reaching the ceasefire deal with Hamas in Gaza, the Israeli army imposed dozens of new road blocks and iron gates and closed most of those which had been opened. The impact was felt immediately on the first day of the prisoners’ exchange between Israel and Hamas, with Palestinian families taking hours to travel between cities and villages. In Hebron, a Palestinian woman in her forties died of a heart attack at a checkpoint trying to reach the hospital.

Every weekend for six weeks — the days on which prisoners were set to be released as part of the ceasefire — the gates closed, and the cage became a palpable reality. Meanwhile, Israel was accelerating its construction work on bypass roads north of Ramallah, south of Nablus, east of Jerusalem, and around Hebron.

At the same time, the Israeli government was also advancing its annexation strategy on the legal front. Just last month, Israel changed the land ownership registration system in the West Bank’s Area C, allowing for the legalization of dozens of settler outposts that had been hitherto unrecognized by the Israeli government, and facilitating the annexation of large swathes of Palestinian public land for settlement expansion.

A month before that, Smotrich and Israeli Defense Minister Israel Katz announced in a televised joint statement that they would accelerate the demolition of Palestinian properties that don’t have Israeli building permits. Smotrich added that Israel was coupling the demolition process with large projects to “bring one million Israelis to Judea and Samaria,” the Israeli term for the West Bank.

Then in early June, Israel announced the building of 22 new settlements, many of which are already-existing settler outposts that will receive government recognition, services, infrastructure, and more land to expand. Jamal Jumaa points out that “the development, expansion, and connection of these settler outposts and new settlements is the real purpose of all the infrastructure projects, which are often justified under ‘security’ reasons.”

“It is one big project, and it is about annexation and the segregation of Palestinians,” Jumaa said.

As Israel continues its new war on Iran, it prolongs these “security” measures even further, using the war to accelerate annexation. Forced to check on social media groups for the situation of the roads, I find myself planning my day around the opening and closure of the gates to my home village. Meanwhile, less than ten kilometers on the other side of the gate, Israeli settlers are establishing a new outpost on land that my family used to farm and no longer has access to, while Israeli army bulldozers continue to work around the clock to build them a new road. They will be able to drive on it without seeing us and being reminded of our existence.

*Featured Image: An Israeli checkpoint east of Ramallah. (Photo: Qassam Muaddi/Mondoweiss)

Qassam Muaddi is the Palestine Staff Writer for Mondoweiss. Follow him on Twitter/X at @QassaMMuaddi.