by Jeremy Kuzmarov, published on CovertAction Magazine, July 14, 2023

From 1959 to 1966, the U.S. illegally stored nuclear weapons in Greenland in preparation for a nuclear attack on the Soviet Union and built an underground scientific research center right out of a James Bond movie.

It resulted in the displacement of natives and has left a residue of environmental destruction in the Arctic that will likely be compounded in Cold War Part II.

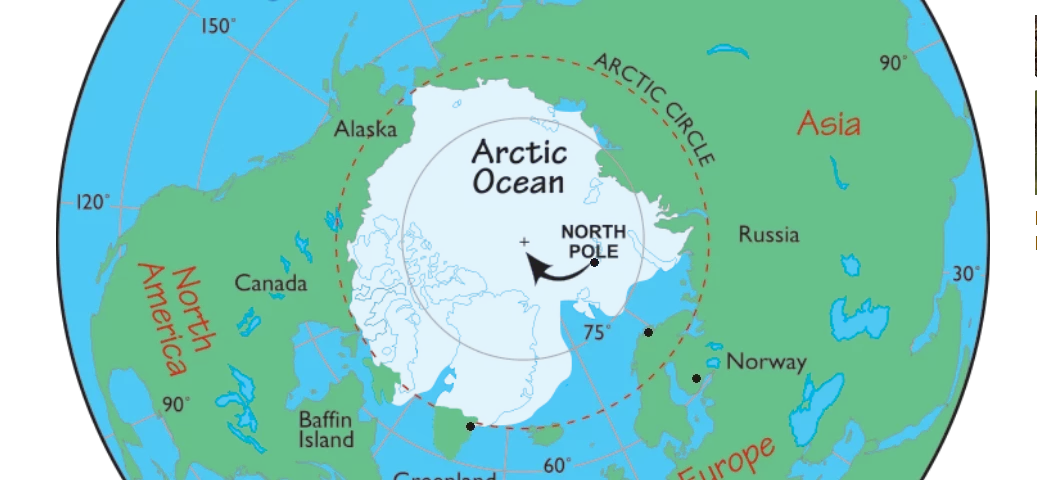

On June 2, Secretary of State Antony Blinken announced that the U.S. would open its northernmost diplomatic station in the Norwegian Arctic town of Tromsoe, the only diplomatic station above the Arctic Circle.

The move comes as competition over the Arctic’s resources with Russia intensifies as polar ice melt opens access to rich mineral resources and the new Cold War heats up.

In 2019, then-President Donald Trump had talked about purchasing Greenland in “the real estate deal of a lifetime” that would help secure a land mass a quarter of the size of the U.S.

Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen called the offer “absurd,” saying that Greenland was not for sale. (Denmark is Greenland’s sovereign owner.)

Beyond Trump’s self-aggrandizement lay a calculating imperial strategy in which the U.S. would use Greenland, where the U.S. already possesses the Thule Air Base, to project its power into the Arctic—a growing arena of geopolitical and military competition.

As part of the Silk Road initiative, China began creating new freight routes extending into the Arctic that would better enable extraction of natural resources while launching a new satellite to track shipping routes and monitor changes in sea ice there.

The Russians have also been busy expanding shipping routes into the Arctic that are navigable because of global warming, and have finished equipping six military bases on Russia’s northern shore and on outlying Arctic Island, while planning to open 10 Arctic search-and-rescue stations, 16 deep-water ports, 13 air fields, and 10 air-defense radar stations across its Arctic periphery.

The Pentagon has further plans to increase its presence and capabilities, with the Army releasing its first strategic plan for “Regaining Arctic Dominance.” The U.S. Air Force has transferred dozens of F-35 fighter jets to Alaska, announcing that the state will host “more advanced fighters than any other location in the world.”[1]

Until now, competition in the Arctic was largely mediated through the Arctic Council, founded in 1996, which includes Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden and the U.S., and promotes research and cooperation. But it does not have a security component, and soon all members but Russia will be North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) members.

Admiral Alexander Moiseyev, commander of Peter the Great, the flagship of the Russian Northern Fleet, accused NATO forces and the U.S. of military actions in the Arctic that increased the risk of conflict.

“There haven’t been so many of their forces here for years. Decades. Not since World War Two,” he told a BBC reporter who told him that NATO blamed Russia for the surge in tension. “We see such activity as provocative so close to the Russian border where we have very important assets. By that, I mean nuclear forces.”

First Ice Cold War

Kristian H. Nielsen and Henry Nielsen,[2] in their recent book Camp Century: The Untold Story of America’s Secret Arctic Military Base Under the Greenland Ice, show that today’s perilous situation has roots in the original Cold War period.

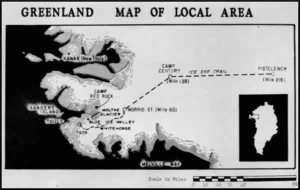

U.S. army engineers then built the subterranean city, Camp Century, under the Greenland ice near the Arctic Circle under the guise of conducting polar research, and explored the feasibility of Project Iceworm, a plan to store and launch hundreds of ballistic missiles with nuclear warheads targeting the Soviet Union from inside the ice.

Described by two Danish journalists as “some monstrous figment of the imagination that could have been featured in an early James Bond film,”[3] Project Iceworm was justified under the 1950s military doctrine of “massive retaliation,” and the Eisenhower administration’s “New Look” policy which advocated for a massive conventional and nuclear arms build-up to counter potential Soviet aggression.

The U.S. had been granted the right to establish military bases in Greenland under the terms of a 1951 Defense agreement signed by Denmark and the U.S. that was based on the terms of NATO.

Two years later, an amendment to the Danish Constitution formally made Greenland part of the unified Kingdom of Denmark, putting the country on an administrative par with a Danish county.

Foreshadowing Trump, U.S. Secretary of State James Byrnes (1945-1947) had tried to buy Greenland for $1 billion from Denmark but to no avail.

The U.S. at the time aspired to build an “Arctic fortress” in Greenland to protect U.S. territory from any potential nuclear or conventional military attack launched by the Soviet Union.

In 1946, General Henry “Hap” Arnold, commander of the U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II, described to National Geographic magazine how, in the future, a surprise enemy attack would be able to come “from the roof of the world,” unless “we are in possession of adequate air bases outflanking such a route of approach.”[4]

His vision—which won support from many other military leaders of his day and remains the basis of the Pentagon’s strategy—was dubbed the “polar concept.” It was embraced by the Strategic Air Command (SAC), which initiated Operation Nanook involving reconnaissance and mapping in Alaska, the Aleutian archipelago, Siberia and northern Greenland.

In 1951, the Truman administration acquired the still operational Thule Air Base in Greenland after signing an agreement to relocate the local population, which consisted of 27 indigenous Inughuit families, with three weeks’ notice.

In November 1952, the first Lockheed F-94B “Starfire” fighter planes arrived to provide air defense around the Thule base, which was an important component in the U.S. polar strategy.

Part of the aim of the Thule base was to provide refueling for long-range Boeing B-29 “Super-fortress” bombers that could fly directly from the U.S. to the Soviet Union with nuclear weapons, including the hydrogen bomb.[5]

The base also functioned as a radar station. From 1958 to 1965, with secret sanctioning by Danish Prime Minister H.C. Hansen, it illegally stored nuclear weapons, including Nike, Hercules and Iceman missiles with nuclear warheads, which would be able to reach targets in the Soviet Union faster than the Minuteman missiles that were stored in the Great Plains.[6]

In 1958, the U.S. secretly began overflying Greenland with B-52s carrying nuclear devices as part of an airborne alert strategy meant to guarantee that America could initiate massive nuclear strikes against the Soviet Union on short notice.[7] The Thule Air Base was also linked to the Ballistic Missile Early Warning System (BMEWS) constructed between 1958 and 1960.

American defense authorities running the U.S. space program had at the time taken a keen interest in northern Greenland, partly as a launching location and practical uplink site for satellites, and partly as a training location for spaceship passengers.

“The City Under Ice”—A Science-Fiction Scenario Come True

In 1960, the U.S. Army began initiating research projects near Camp Thule at the underground, nuclear-powered Camp Century, which was established as a kind of science-fiction scenario come true.

The scientists and military personnel were flown into Camp Century on a modest air strip. They lived in underground bunkers that were connected to kitchen and living facilities that included a library as well as their research station through a network of underground tunnels stretching for more then 6,000 feet.[8]

The latter were dug using a Swiss invention, the Peter Plough, that used rotating shovel blades to strip a one-to-two foot layer of snow off the surface, blowing it high into the air and off to one side.

The sub-surface installation of a nuclear reactor within the Greenland ice sheet at Camp Century was an enormous and difficult engineering endeavor that was an astonishing achievement.

The scientists were able to drill to the very bottom of the ice sheet and extract an unbroken core of the ice 1,390 meters (4,560 feet) long, a sample that helped Danish and American glaciologists attain a new and deeper understanding of the Earth’s climate over the past hundred thousand years.

Almost all of the journalists invited to visit Camp Century in the early 1960s celebrated the major scientific achievements while minimizing the Cold War context and military purposes behind the camp.

Characteristic was CBS’s star reporter (and future anchorman) Walter Cronkite, who went to the newly constructed Camp Century in the summer of 1960, and produced a widely viewed television broadcast, “The City Under Ice,” which aired in January 1961.

“The City Under Ice” included an interview with Captain Thomas Evans, the head of Camp Century, who described the Army’s achievement as having conquered “one of the last frontiers on Earth,” by stationing an entire unit inside the ice sheet.

The program demonstrated that life at Camp Century—“the city under ice”—was quite comfortable and safe even though, during the winter months, the temperature “falls to 70 below zero [-57 Celsius] and the wind howls with a speed of 100 miles [161 km] per hour.”

Cronkite explained to his American viewers that Greenland was a Danish island “on top of the world” and that Denmark, “a fellow NATO member,” had been so kind as to give the Americans permission to set up an important radar station and a large air base at Thule—in addition to Camp Century, located on the ice cap.

Despite these statements, Cronkite primarily underscored the scientific and technological aspects of Camp Century, focusing on the battle to subdue nature, not the Soviet Union.

In accepting this official billing as a “scientific facility,” Cronkite obscured that the scientists working out of Camp Century were involved in acquiring little-known information about the geographical and meteorological conditions in Greenland and the Arctic, which was needed for realizing the polar strategy and establishing U.S. military supremacy in the Arctic.[9]

More forthright was an American journalist writing under the pseudonym “Ivan Colt” who, in an article appearing in October 1960, included a vivid description of missile-launching bases beneath the surface of the ice sheet that would be “able to plaster every major Soviet city, H-bomb depot and missile plant.”

Audacious Cold War Project

These missiles would be protected because of their distance from the U.S. mainland, and location in a secret underground facility.

Nielsen and Nielsen write that “Denmark was fully as surprised as Greenland at the revelation of the huge and audacious Cold War project, which had been planned in utmost secrecy by strategists at the Pentagon.”[11]

Health and Environmental Detritus and the Dangers of History Repeating Itself

Camp Century was shut down in 1966, as its sub-surface tunnel system in the Greenland ice sheet was extremely difficult and costly to maintain and the development of Polaris nuclear missiles launchable from submarines made it largely obsolete. However, its remains may soon resurface because of global warming.

Greenland, today a largely self-governing part of Denmark, threatened to bring the case before the UN International Court of Justice if Denmark did not promptly assume responsibility for cleaning up the Camp Century site.

The remaining debris, some 35-70 meters (115-230 feet) beneath the surface of the ice, is known to include not only buildings and structural elements but also radioactive, chemical and biological waste.[12]

Over the years, many workers at Thule Air Base had developed cancers from radiation exposure, as did members of a clean-up crew that was called in to collect snow contaminated with plutonium for transport to the U.S. after a B-52 Stratofortress carrying hydrogen bombs crashed seven kilometers from Thule Air Base in 1968.[13]

The health and environmental detritus is an example of a vast and unrecognized cost of the Cold War arms race that is sadly being reinvigorated today.

As Russia, China and the U.S. compete for renewed control over the Arctic and set up yet more military bases there, the fallout will again be considerable even if the nukes are never deployed, and the tragedy of Camp Century will be repeated.

-

- In 2018 NATO set up a new operational command based in Norfolk, Va. whose purpose is to defend the Atlantic sea routes, Scandinavia, and the Arctic. On June 4, The New York Times further reported that Canada was expanding military exercises on the Arctic frontier near Nunavut using Inuit soldiers when the Inuit had a long history of being manipulated by the Canadian government. Norimitsu Onishi, “In Power Struggle Over the Arctic, Canada Turns to Those Who Know it Best,” The New York Times, June 4, 2023, A1. In February 2023, the U.S. launched a month-long military exercise, hosted by Finland and Norway, nicknamed Arctic Forge 23, which the Pentagon’s European Command described as a way to “demonstrate readiness by deploying a combat-credible force to enhance power in NATO’s northern flank.”

- Kristian and Henry Nialsen are professors at Aarhus University in Denmark. ↑

- Kristian H. Nielsen and Henry Nielsen, Camp Century: The Untold Story of America’s Secret Arctic Military Base Under the Greenland Ice (New York: Columbia University Press, 2021), 256. ↑

- Nielsen and Nielson, Camp Century, 8. ↑

- The Danish hush-hush policy about American aircraft crossing Greenlandic air space carrying nuclear devices and about the clandestine storage of such weapons at Thule Air Base and exposure of employees to radiation was exposed in Danish journalist Poul Brink’s book, The Thule Affair: A Universe of Lies. ↑

- The storing of nuclear weapons was illegal because the Danish Parliament never authorized it. It was only in 1995 that the U.S. government admitted to storing the weapons. ↑

- Under President Kennedy, the Airborne operation publicly became known as “Chrome Dome,” which kept at least a dozen B-52s armed with nuclear devices in the sky at all times, day and night. ↑

- Plans were in place to connect the underground tunnels by a sub-surface railway that would connect Camp Century and the Thule Air Base, though the construction never came to fruition. ↑

- In 1950, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers established a new scientific institute called the Snow, Ice, and Permafrost Research Establishment (SIPRE), whose mission was to “provide the military establishment with data, which can be used as a basis for increasing the efficiency of military operations in an environment dominated by the presence of snow, ice, seasonally frozen ground or permafrost.” ↑

- In April 1997, control of Thule Air Base was transferred from the U.S. North Atlantic Command to SAC, and its status was changed from a support base with refueling planes into an actual operational base for strategic bombers. ↑

- Nielsen and Nielsen, Camp Century, 3, 4. ↑

- Nielsen and Nielsen, Camp Century, 1. ↑

- Tuk Erik Jorgen-Jensen, an employee of the Danish Defense Intelligence Service (DDIS) stationed in Greenland from March 1960 to August 1963 at Thule Air Base, met with a Captain Page who worked at the PM-2A nuclear reactor at Camp Century. Page came to look more and more ill, and suddenly left the camp. Jorgen-Jensen is convinced that Page had been subjected to an excess of radiation when the reactor was started in October/November 1960 and that there were problems with radiation levels exceeding the permitted limits. ↑

Jeremy Kuzmarov is Managing Editor of CovertAction Magazine. He is the author of four books on U.S. foreign policy, including Obama’s Unending Wars (Clarity Press, 2019) and The Russians Are Coming, Again, with John Marciano (Monthly Review Press, 2018). He can be reached at: jkuzmarov2@gmail.com.