by Fergie Chambers, published on Towards Freedom, March 21, 2022

CHISINAU, Moldova—Nestled above the Black Sea, between the war zone in Ukraine and the eastern limits of NATO territory in Romania, sits the tiny, oft-forgotten landlocked nation of Moldova. Among the poorest countries in Europe by just about any relevant metric, it has been overwhelmed by Ukrainian refugees in the three weeks since the outset of what Russia calls its “special military operation” (спецоперация) in Ukraine.

More than 359,000 people of the 3.38 million who have fled Ukraine since February 24 have passed in and out of the country, according to the United Nations Commissioner for Refugees. Roman Macovenco of the Moldovan Consular Directorate confirmed at least 300,000 Ukrainians had crossed through Moldova. The vast majority came through the border town of Palanca, just 57 kilometers (or 35 miles) from Ukraine’s Odessa. Many wound up in Chisinau, the tiny country’s capital. As of March 14, roughly 100,000 remained in Moldova.

Primarily due to its limited capacity and even more limited financial resources, Moldova is a transitional zone for refugees. Though, the length of their stay depends on their economic status. Moldovan Ministry of Interior Principal Specialist Olesea Sirghi and Macovenco said the refugees who remain for more than two days cannot afford passage to EU countries.

‘Oligarchs Who Drink, Complain and Chase Women’

This reporter learned from local people that the first wave of refugees was made up of almost exclusively wealthy elites.

Misha Tsarkisan is a Georgian migrant who has lived for years in Moldova and does maintenance work near one of Chisinau’s primary refugee centers. He described the initial wave as “oligarchs, who came to drink, complain and chase women.”

Similar sentiments can be heard everywhere in the capital, though they are often expressed with more nuance. Ion Popov, 25, moved his coffee truck near a bus depot that dealt with the influx of refugees. He told Toward Freedom the arrivals were as mixed in their attitudes and temperament as any group might be.

“The rich loaded their things up in their cars with as much money as they could gather, and have generally behaved rudely,” Popov said. “I don’t know how you can be in such a situation and expect to make demands. But you know, many of these people are just caught in a bad situation, and many of them are perfectly decent.”

Moldova’s split identity, vacillating between former Soviet, Russian, Romanian and independently Moldovan, lends to these simmering tensions.

For less affluent refugees, the primary destination is the International Exhibition Center MoldExpo, the largest complex of any sort in the country. The scene on March 14 featured police checkpoints, buses coming and going, and makeshift kiosks-turned-sleeping-quarters. Visitors ranged from young volunteers to European reporters, as well as a troop of “Dream Doctors.” These entertainers were dressed as clowns to provide limited medical care. An Israeli non-governmental organization (NGO) had flown them in from Tel-Aviv (Occupied Jaffa).

The center itself is a collection of concrete buildings, offset from a wooded park that boasts a Soviet-era “Hall of Fame” featuring a collection of statues: Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels and the towering centerpiece, Vladimir Lenin.

Inside the center, refugees are served food and drink, and can access donated items, such as clothing, diapers and medical equipment. About 200 people appeared to be in that case, sleeping on cots. The majority came from the southwestern Ukrainian cities of Odessa and Mykolayiv, but also from the capital, Kyiv.

From Chisinau, NGO-sponsored buses take off to EU countries, but most especially to Germany and Poland. In some cases, the embassies of EU countries are paying for the buses. According to the aforementioned Moldovan officials as well as an NGO representative, the EU has pledged about $20 million in support funds to Moldova. Far more buses await at the Romanian border, as Romania simply has more infrastructure as well as the presence of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the United Nations. People with even modest means appeared able to find a way to arrange passage to Romania. But those Ukrainians who are completely destitute often remain in the shelter.

Refugees Speak Out

Contrary to the narratives with which the Western public has been inundated, Ukrainian refugees expressed largely divergent positions on the causes and potential outcomes of the conflict. This reporter witnessed EU-zone reporters gravitating toward the far fewer refugees who held pro-Kyiv positions. Not a single foreign press crew had a Russian- or Ukrainian-speaking member in tow, making it less likely they would hear from working-class Ukrainians, who mainly spoke Ukrainian or Russian.

Toward Freedom spoke at length in Russian with several refugees. What stood out was how few of them lent unequivocal support to the government of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky.

Alex Kirillov, a 40-year-old restaurateur originally from Donetsk, had left Kyiv four days earlier with his wife and three children. His main focus on the situation back in Ukraine was what he called a “real problem with nationalist aggression.” He saw no way out of the war without compromise and neutrality. Kirillov said the war had begun eight years ago. “Zelensky’s breaking of the Minsk agreements [ceasefires in Donbass brokered between Moscow and Kyiv] was the only reason this new stage of the war began.” He described pre-2014 Ukraine as “very calm, not as stable as the USSR, but much better than after Maidan, when things became economically unstable and full of war.” Maidan was the series of 2013-14 protests that led to the coup that ousted democratically elected President Victor Yanukovych. Kirillov said the U.S. and NATO supply of weapons to Ukraine worsened the situation. “But, then of course, allies must do this.” He was adamant that Putin, whom he disliked, had zero intention of going past Ukraine, or of even annexing Ukraine itself, and that it was naive to believe otherwise.

Claims have emerged that Russian and Ukrainian troops are being violent toward civilians and journalists. “We have no idea about any of this, as there is so much propaganda,” Kirillov said. “My house is safe, but we did hear bombs, and wanted to leave with the children.” Zelensky, in his eyes, had unwittingly allowed the United States to “poke the Russian bear.” He reiterated Ukrainians and Russians had always seen one another as brothers, a refrain this reporter repeatedly heard from refugees living at the MoldExpo. Then a large white charter bus appeared, he and his family said their goodbyes, and they were off to Belgium.

Oksana Novidskaya, from the southern Ukrainian city of Mykolayiv, found herself in the center with her two teenage children. Her 19-year-old daughter, Sofia, carried a 2-year-old. Novidskaya said a bomb went off near her former classmate’s house. That’s when she decided to leave with her children. “I am not interested in politics, nor do I understand them,” she said. “But I want Russia to stop attacking. All I know is that Russians and Ukrainians should help each other.” Her brother stayed back to fight with the Ukrainian army. As of March 11, he was still okay. When this reporter inquired about her thoughts on the Donbass, Novidskaya did not wish to discuss. Later, she secured a ride to Romania, so she could get to where her mother lives in Italy.

‘The West Was Silent’

Meanwhile, emphatic in opposition to the Ukrainian government was Alec Shevchenko, a 70-year-old former prosecutor from Kharkiv. He approached this reporter, eager to share his perspective, speaking with such vigor that a few dozen other refugees gathered around to witness the conversation.

“This war started when the Ukrainian government began bombing homes in Donbass! The West was silent then. Millions of people live there, you know?”

A civil war began in Ukraine in 2014 after the majority Russian-speaking Donbass region containing two provinces, Donetsk and Lugansk, began breaking away from Ukraine after witnessing the neo-Nazi and nationalist-infused Maidan protests. The provinces announced their secession as independent republics after holding successful referenda. The 2015 Minsk agreements were intended to end the fighting. However, the Ukrainian government has violated the agreements to appease nationalists and neo-Nazis. Since then, more than 14,000 people have been killed in the eastern Ukrainian region and 1.5 million have been displaced.

Shevchenko, who had lived in Ukraine his entire life, then lit a cigarette and demanded this reporter take one as well.

“After the Nuremberg Trials, there were no more fascists in the USSR. People from all the Soviet republics—Tajiks, Georgians, Russians, Ukrainians—all lived together happily. But after 1991, suddenly there were some Nazis again. And after 2014, they began to dominate things in Ukraine.”

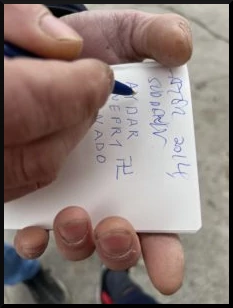

Those are the names of Ukrainian military battalions. Then Shevchenko drew a swastika, and said in English, “These guys!” In his view, explicit Nazis were a minority in the government itself, which he described as full of “actors, athletes, ballerinas and clowns.”

The former prosecutor went on to say the United States and Kyiv had protected and encouraged the military battalions. Putin, in his eyes, was someone who moved deliberately. “He protects his people and his borders. If he was aggressive, like Hitler—as they are saying in Europe—he would have invaded Ukraine 8 years ago.” He gave a strong stare, and said, “Write this down: 80 percent of the Ukrainian people are glad that the Russian army has come. But they are terrified to say so publicly, especially now, because these Nazis will kill them.” The surrounding crowd appeared unfazed at his commentary.

Recent polls on the war have relayed Russian and U.S. public opinions. However, one poll conservative British billionaire Michael Ashcroft conducted March 1 to 3 claims most Ukrainians disfavor Russia, see Russians as kin, favor Europe, approve of NATO expansion, prefer not to leave Ukraine and wish to pick up arms to defend Ukraine.

What was clear in these and other exchanges is the reality of the East-West split in Ukraine, with anti-Russian sentiment the strongest in the west. “[Russians] would never want to kill Ukrainians for no reason,” one refugee, Dima Chumak, 48, of Mykolayev, told Toward Freedom during the conversation with Shevchenko. “But the nationalists want to kill Russians in the east for fun.” What is certain is, like in Syria, Iraq and other U.S.-inspired conflicts, public opinion on the ground is not as uniform as the Western press makes it seem.

*Featured Image: An array of people TF contributor Fergie Chambers interviewed in Moldova / credit: Fergie Chambers

Fergie Chambers is a freelance writer and socialist organizer from New York, reporting from eastern Europe for Toward Freedom. He can be found on Twitter, Instagram and Substack.