by Noura Erekat and John Reynolds, published on TWAILER Review, 2021

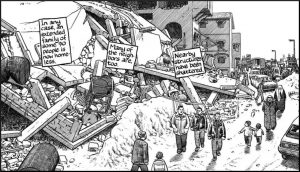

At the end of 2008, Israel went to war on the Gaza Strip on a scale not seen in Palestine for decades. The Israeli military’s International Law Department had spent months prior crafting ‘legal advice that allowed for large numbers of civilian casualties’. This heralded the starting point of formal Palestinian interaction with the International Criminal Court, with an initial failed attempt by the Palestinian authorities to trigger ICC jurisdiction over crimes committed in occupied Palestine. It would be a long twelve years before eventually, in February and March 2021, the ICC’s Pre-Trial Chamber ruled that the Court does indeed have jurisdiction and the Prosecutor confirmed that an investigation will now proceed. Through these years, the Office of the Prosecutor often appeared at pains to draw out the wrangling over the preliminary question of whether it could accept jurisdiction. In the meantime, Gaza was besieged and bombarded, again and again: ‘sky of knives … reincarnation of metal, children limp grey dust beneath buckled buildings’, as captured by Hala Alyan. This materialised most devastatingly in Israel’s 2014 war on Gaza. Its modalities of lethal force were also adapted in 2018 to maim and execute Palestinians demonstrating in the Great March of Return.

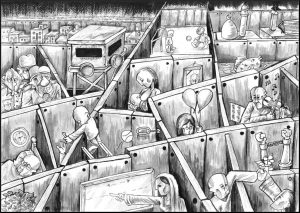

This hot violence of intense and spectacular military assault – airstrikes and artillery shelling, sonic booms and white phosphorous, home demolitions and shoot-to-kill sniping, plus the resistance of Palestinian armed groups (of a decidely lesser scale and ‘gravity’ in its reach) – will be an obvious focus for the ICC investigation into events from June 2014 onwards. But ‘not all violence is hot’, as Teju Cole succinctly surmises. The slow, cold violence of Israeli apartheid has continued to plough its furrow ever-deeper. This encompasses the settlement project and economic exploitation of Palestinian land and labour in the West Bank, the blanket denial of Palestinian refugee return, and the Israeli state’s exclusionary constitutionalism. As Hassan Jabareen shows, it transcends the partition lines and permeates through a single legal order of Israeli racial domination over the Palestinians. All of these elements are ongoing, all are pillars of what Lana Tatour emphasises as the overarching settler-colonial structure of apartheid – and all are potentially within the remit of the ICC.

And so our purpose here is not to dwell on the technicalities around jurisdiction, but rather to take the ICC conjuncture as grounds for reflection on the politics of Palestinian legal engagement. We situate this reflection in the larger context of Israeli colonial-apartheid, thinking about Palestinian legal tactics – and the charge of the crime of apartheid in particular – in relation to political strategy. Conscious of the limits of international criminal law, we are at the same time animated by the question of whether the turn to international criminal justice as a site of struggle can feed into the more radical transformations of social, economic and ecological relations that are needed for settler-decolonisation1 and liberation of Palestine.

Warfare, Lawfare and the Limits of International Criminal Law

Many may consider criminal investigation and prosecution for purposes of accountability and deterrence to be sufficient ends in themselves. Our particular concern is the potential of the ICC bid, precipitated as it was by the hot violence of the Gaza wars, to foment a rupture whereby an international tribunal contends with the cold violence of Israeli apartheid. We are clear that law itself, especially international criminal law, is ‘insufficient to lead Palestinians to emancipation’. Beyond the general incapacities of individualised responsibility to produce social transformation, we agree with and are engaged in particular critiques of international criminal law that have come from TWAIL and Marxist perspectives: of international criminal law as ‘reproduction of the civilizing mission’ and ‘capitalism’s victor’s justice’.

The ICC itself is a political institution which ‘operates ideologically’ as part of our contemporary global order to ‘sustain prevailing constellations of power’. Kamari Maxine Clarke has shown how the Court reifies white supremacy and helps mask and perpetuate core-periphery relations of economic exploitation and inequality. If the institutional dynamics at the UN were different, we would certainly be directing all arguments and energies towards the necessity of political and economic sanctions against Israel itself rather than criminal prosecutions of some officials. As things stand, however, the ICC is the institutional door that has been forced ajar, and so it is imperative to think about what space it may open for anti-colonial forms of ‘principled opportunism’.

With this in mind, we support the sentiment that the jurisdiction decision was a victory for Palestinian legal activists and a testament to their tireless work. The functional question of whether the ICC could accept jurisdiction over a situation in Palestine under the Rome Statute should have been straightforward – if not in response to the initial request in 2009, certainly after Palestine was admitted as a full member of the Court in 2015. Yet there was a very real possibility that the ICC would have found a way to reject jurisdiction as advocated by the ‘strained arguments and conspicuous hypocrisy’ of Israel-supporting ICC members, or to continue to drag out any decision indefinitely. And so the victory, such as it is, was hard-fought. It is a victory for Palestine over major ICC member states such as Germany, Canada, Brazil and Uganda who actively intervened to advocate that the Court refute jurisdiction (with Brazil and Uganda taking ‘manisfestly incoherent’ positions against their own pre-existing recognition of Palestine, in favour of new-found neocolonial alliances). It is vindication for Palestinian rights organisations over the Israeli Attorney-General and the self-proclaimed ‘leading experts on international law’ who feature on a mock ‘ICC Jurisdiction’ website sponsored by Israel’s Ministry of Strategic Affairs.

At the same time, the victory is very much provisional. Political hurdles, in the form of Israeli and US opposition backed up by quintessential European duplicity, have been surmounted for now but will redouble in the higher-stakes contestations to come. Such external pressures will compound the particular technical and logistical challenges of prosecuting Israeli personnel in a context of staunch formal non-cooperation from Israel, and the potential for jurisdiction challenges to arise again in individual cases. Funding and basic administrative challenges are also an ongoing material issue for the Court. In her statement confirming that an investigation will now be initiated, the Prosecutor was careful to temper expectations in terms of the priority and pace of proceedings, as well as striking an almost contrite tone to convince Israel to trust the ICC.2 Still, Israel confirmed it does not recognise the Court’s authority and will not cooperate with the investigation. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu characterised the Court’s decision to accept jurisdiction as ‘pure antisemitism’. This absurd claim fits the Israeli playbook. Israel and its Ministry of Strategic Affairs have spent the last fifteen years trying to undermine the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) movement, and are now deploying similar tactics to delegitimise the ICC. The appointment of an army Major General3 rather than a lawyer to ‘lead the battle against the ICC’ highlights, as observers have quipped, that Israel’s ‘lawfare’ is ‘getting increasingly literal’. In this context, questions of strategy and tactics are crucial.

Tactics and Strategy

In the New Left Review in 1971, Palestinian intellectual and PFLP spokesperson Ghassan Kanafani emphasised the need for anti-colonial struggle not to be dictated by ‘bourgeois moralism and obedience to international law’. There is a legitimate critique that, over the decades since, the Palestinian liberation project has become overly dominated by legalism and, more generally, has functioned to assuage power structures rather than disrupt them. Mezna Qato and Kareem Rabie make the case persuasively that organising around international law involves a reduction of the original and higher aim of ‘until liberation and return’ to a less ambitious and ultimately self-defeating resort to liberal legalism. Conscious of international law’s own colonial entanglement, they argue that law-based advocacy ends up being geared ‘towards a better colonialism rather than the end of colonialism’. By fixating on Israel’s excesses and not Zionism’s essence, legalist advocacy elides the state’s settler-colonial nature and the underpinning structures of imperialism and capitalism. In this sense, it is ‘problematic to pivot movement strategy on bodies of law that emerged in order to regulate imperialism, and that often function to legalize Israeli colonization’.

The reference to strategy here is key. Strategy cannot hinge on law. But in certain conditions, legal tactics may work to support transformative strategy. What is needed most in the Palestinian context, as we have both argued previously drawing on the work of Duncan Kennedy, Robert Knox and others, is ‘a coherent political strategy towards which appropriate legal tactics are thoughtfully deployed’ and ‘a robust political movement to inform legal advocacy and to leverage tactical gains’. In this sense, engagement through law requires an acute understanding of international legal institutions as a field of political struggle. Knox and Ntina Tzouvala trace the lineage of such thinking in anti-colonial movements back to the Bolshevik theory of imperialism, which had ‘a certain irreverence for international law, and an explicit sense that it needed to be subordinated to the wider anti-imperialist project’.

There is a rich and growing tradition of Palestinian scholars and activists today who are thinking deeply about these dynamics in various iterations as well, including George Bisharat, Lana Tatour, Mazen Masri, Nimer Sultany, Samera Esmeir, Yara Hawari, Rafeef Ziadah, Suhad Bishara, Victor Kattan, Nahed Samour, Nadija Samour, Emilio Dabed, Ardi Imseis, Ata Hindi, Hadeel Abu Hussein, Reem al-Botmeh, Hassan Jabareen, Munir Nuseibah, Reem Bahdi and Mudar Kassis, and many more. Certain core threads run through their work: Israel’s settler-colonial essence; its oppression of the Palestinians as a whole; the one-state reality over the fictions of partition; law as often central to these problems; and the necessity of political strategy in relation to law, rights, development, recognition, and so on. Masri’s articulation is illustrative: ‘law and legal tactics cannot replace strategy, but they can play a role in a strategy – one that enjoys a high level of support, mobilizes the grassroots, employs a range of tools and is guided by a clear vision’.

In this sense, there is scope for principled anti-apartheid legal tactics to trigger transformational possibilities, if harnessed effectively under the right conditions in service of a cogent political strategy. However, given the current state of the Palestinian leadership, and the disconnects between Palestine’s political institutions, popular movements and global solidarity campaigns, such conditions and strategy remain distant. Following the PLO’s abandonment of the single democratic state strategy and its ‘pragmatic revolutionary’ tactics, and especially since the collapse of the Camp David talks signalling the putative death of the Oslo peace process, the Palestinian leadership has pursued a politics of acquiescence. They have placed faith in the idea that good native behaviour will be rewarded with imperial benevolence, despite consistently damning evidence to the contrary. Palestinian foreign policy is, of course, subject to larger systemic coercive forces, and the ‘sovereignty trap’ that presently incapacitates it is constructed by international relations and international law. But Palestinian officialdom has also sacrificed vital opportunities over the past two decades to reconstruct a serious anti-colonial political strategy and to channel available legal mechanisms accordingly.

The 2004 ICJ Advisory Opinion on the Wall offered a major opening for the Palestinian official leadership to build an alliance towards pushing UN members not to recognise or assist the illegitimate occupation infrastructure – to divest from and sanction Israel. Palestinian civil society played its part by launching its BDS call in 2005 on the first anniversary of the ICJ opinion. This was inspired by the struggle to abolish apartheid in South Africa, and sought to build upon and expand the growing global anti-apartheid movement for Palestine. The Palestinian leadership should be mirroring this at an institutional level. It could have formulated an expansive, proactive strategic vision of decolonisation with which the BDS tripartite goals (ending occupation and colonisation, full equality, refugee return) align. The Palestinian leadership has instead been preoccupied with ‘preening like a state’ – even if that means a limited Bantustan state – and its legal initiatives have been haphazard and reactive. Rather than lead an anti-apartheid freedom struggle, the Palestinian Authority has been implicated in neoliberal apartheid and unequal capital accumulation.

This context has underpinned ongoing debates among Palestinian legal practitioners and scholars that consider what Palestinians can realistically obtain in court settings, versus what Palestinians need to do in order to catalyse fundamental paradigmatic shifts at the real cost of losing legal contests along the way. We are sympathetic to the school of thought that favours pragmatic and legalistic advancements over more radical tactics. But in the absence of an institutional strategy to harness any such incremental advances, we find this approach uncompelling.

How then does a more radical tactical approach overcome the debilitating lack of a visionary programme from above? It doesn’t. It is, rather, a bet placed on the capacity of movement to develop strategy in the course of what will be an explicit and pitched political contest. This approach seeks to propel strategic coherence from below in the course of fervent but fluid struggle and provocation, based on historical evidence that societies can be prepared for transformative social justice movements but cannot dictate them. This approach may be fraught, but in light of the current status quo and uninspiring alternatives, there is little to lose. Thinking about this in the context of the ICC involves acceptance of the limits of the process on its own terms and places focus on how it is harnessed tactically in the ‘legitimacy war’, regardless of victory or defeat in the courtroom. Criminal prosecutions, even if they happen, will not deliver justice for the Palestinians in the larger sense of the settler-colonial structure that shapes their lives. The struggle will remain political.

With that in mind, what tactical opportunities can be located in the ICC’s exercise of jurisdiction? Michael Kearney has done important analysis on both the war crime of transfer of settlers and denial of the right to return as a crime against humanity, while Palestinian organisations have flagged the pillage, extraction and destruction of Palestinian natural resources. These are all essentially forms of colonial crime within the jurisdiction of the Court, and offer avenues into unsettling certain facets of Zionism through their prosecution. The larger structural framework within which these crimes are all committed, however, is the Israeli apartheid regime over Palestinians. Exposing the crime against humanity of apartheid itself can potentially work in tactical service of broader anti-apartheid political strategy and grassroots organising. It can also operate as a crucial bridge on a number of fronts: linking together the hot violence of Israel’s war crimes with the cold violence of its legal structures of dispossession, exclusion and persecution; reconnecting the partitioned but shared realities of occupied, exiled and citizened Palestinians under Israel’s constitutional order; and mapping the trail from individual responsibility for crimes of apartheid to state responsibility and sanctions for maintaining an apartheid regime.

We Charge Apartheid?

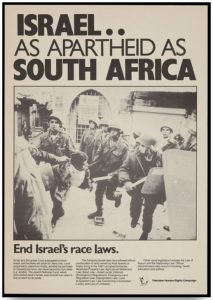

The controversy which engulfed the UN’s 2001 Durban anti-racism conference was precipitated by the insistence of social movements from around the world on calling Israel out as an apartheid state. This was a political and moral argument to challenge institutionalised racism against Palestinians in the context of global anti-racist action. The anti-apartheid framework became increasingly central to political organising and global solidarity through the Palestinian BDS call and initiatives like Israeli Apartheid Week. More recently it has informed renewals of Black-Palestinian solidarities and the Black Lives Matter demand for divestment from apartheid Israel. While Palestinians had diagnosed and detailed Israeli apartheid conditions for many decades prior, the concomitant international legal arguments had only started to be developed in the 1990s by individual scholars and Palestinian rights organisations. More concerted legal analyses likewise began to follow after Durban. Palestinian organisations like Badil, Al-Haq, Adalah, and Stop the Wall applied the prohibition of apartheid as part of their deconstruction of Israeli law and policy. International legal studies, scholarship and reports steadily mounted. The Russell Tribunal on Palestine deliberated the issue in Cape Town and concluded that ‘Israel’s rule over the Palestinian people, wherever they reside, collectively amounts to a single integrated regime of apartheid’. The UN Special Rapporteurs, CERD Committee and ESCWA Commission made similar findings in their own spheres.4 There is clear momentum.

After Palestine joined the ICC in 2015, a collective of Palestinian rights organisations began to file submissions to the Prosecutor detailing crimes committed by high-level Israeli civilian and military officials. The first three submissions related to the hot violence of the wars and siege on Gaza. The fourth, a 700-page brief submitted in 2017, covered war crimes and crimes against humanity in the West Bank – including the crime of apartheid. Following the Pre-Trial Chamber’s February 2021 jurisdiction decision, the organisations reiterated the charge, albeit limited in this context as it is to the manifestations of apartheid in the West Bank: Israel’s systemic segregation and subjugation of the Palestinians constitute ‘an institutionalised regime of racial domination and oppression, and amount to the crime of apartheid; it is imperative that the Prosecutor include acts of apartheid in the scope of her investigation’.

While Palestinian rights organisations filing submissions to the ICC today are more legalistic in their approach and less radical in their politics, we understand their ‘charge’ of apartheid as carrying some echoes of the We Charge Genocide petition submitted by the Civil Rights Congress to the UN in 1951. Knox and Tzouvala recount how the Black radicals behind that petition were informed by Marxist conceptions of imperialism and political economy as much as by the Genocide Convention itself. The petition represented a ‘tactical deployment of international law in order to serve broader purposes of radical social transformation’, and was consciously aimed at ‘connecting US racism at home with structures of US imperialism abroad’. It was ‘invoked tactically to strengthen those forces who were opposing racism and imperialism’ more than in expectation that an international legal process would itself resolve deep racial injustice in the United States. Coming at a crucial transitional moment for the Black freedom movement, UN institution-building processes, Cold War manoeuvring, and Third World liberation struggles alike, the petition was significant in mobilising internationalist support and damaging US delegations at the UN. Eleanor Roosevelt lamented that the petition was so ‘prominently featured in the papers’5 during the UN General Assembly in Paris and admitted that ‘we were hurt in so many little ways’ by it. It also had lasting ramifications within the US, both on the back of its submission to the UN and its wide circulation in book form. It exposed the extent of ongoing racial violence, ‘whipped up the kind of necessary pressure that led to the final cracking of the spine of Old Jim Crow’,6 and charted a more radical course for equality struggles that continues to reverberate. William Patterson, primary architect of the petition, was forthright in response to criticism of his organisation’s ‘politicisation’ of civil rights by conservative and anti-communist elements of African-American leadership: ‘The attitude of using only the legal approach had something of the Booker T. Washington in it. The NAACP leadership did not understand the gravity of the situation’.7

After Palestine joined the ICC in 2015, a collective of Palestinian rights organisations began to file submissions to the Prosecutor detailing crimes committed by high-level Israeli civilian and military officials. The first three submissions related to the hot violence of the wars and siege on Gaza. The fourth, a 700-page brief submitted in 2017, covered war crimes and crimes against humanity in the West Bank – including the crime of apartheid. Following the Pre-Trial Chamber’s February 2021 jurisdiction decision, the organisations reiterated the charge, albeit limited in this context as it is to the manifestations of apartheid in the West Bank: Israel’s systemic segregation and subjugation of the Palestinians constitute ‘an institutionalised regime of racial domination and oppression, and amount to the crime of apartheid; it is imperative that the Prosecutor include acts of apartheid in the scope of her investigation’.

While Palestinian rights organisations filing submissions to the ICC today are more legalistic in their approach and less radical in their politics, we understand their ‘charge’ of apartheid as carrying some echoes of the We Charge Genocide petition submitted by the Civil Rights Congress to the UN in 1951. Knox and Tzouvala recount how the Black radicals behind that petition were informed by Marxist conceptions of imperialism and political economy as much as by the Genocide Convention itself. The petition represented a ‘tactical deployment of international law in order to serve broader purposes of radical social transformation’, and was consciously aimed at ‘connecting US racism at home with structures of US imperialism abroad’. It was ‘invoked tactically to strengthen those forces who were opposing racism and imperialism’ more than in expectation that an international legal process would itself resolve deep racial injustice in the United States. Coming at a crucial transitional moment for the Black freedom movement, UN institution-building processes, Cold War manoeuvring, and Third World liberation struggles alike, the petition was significant in mobilising internationalist support and damaging US delegations at the UN. Eleanor Roosevelt lamented that the petition was so ‘prominently featured in the papers’5 during the UN General Assembly in Paris and admitted that ‘we were hurt in so many little ways’ by it. It also had lasting ramifications within the US, both on the back of its submission to the UN and its wide circulation in book form. It exposed the extent of ongoing racial violence, ‘whipped up the kind of necessary pressure that led to the final cracking of the spine of Old Jim Crow’,6 and charted a more radical course for equality struggles that continues to reverberate. William Patterson, primary architect of the petition, was forthright in response to criticism of his organisation’s ‘politicisation’ of civil rights by conservative and anti-communist elements of African-American leadership: ‘The attitude of using only the legal approach had something of the Booker T. Washington in it. The NAACP leadership did not understand the gravity of the situation’.7

Though coming in a very different moment and political context,8 the Palestinian activist charge of Israeli apartheid is a comparable vanguard assertion of institutionalised oppression as international crime beyond what mainstream representatives of the oppressed group have articulated. It is likewise one which the offending state goes to great lengths to undermine as beyond the pale. Crucially, it is also the legal claim that most directly feeds into the mass popular mobilisation of Palestinian and global social movements over the last twenty years, which have emphasised the racialised legal structure of settler-colonial dispossession.

Even with this relatively radical approach, the distinct tactical risks in engaging the ICC generally and the crime of apartheid specifically must be acknowledged. Most obviously, it is a tactic without control over the agenda when compared with other forms of civil or inter-state litigation. The Prosecutor may choose to ignore apartheid entirely and focus the investigation on more discrete war crimes, irrespective of Palestinian interventions.

Warning signs are already there in the scope of the investigation. In the Prosecutor’s summary of preliminary examination findings, several crimes are identified as likely to have been perpetrated. The document refers to five categories of war crimes committed by Israel – four specific to Gaza, plus transfer of settlers into occupied territory – and six categories of war crimes when it comes to Palestinian armed groups. There is no reference to apartheid or any other crimes against humanity. That said, the document emphasises that the crimes mentioned are ‘illustrative only’ and the ‘investigation will not be limited only to the specific crimes that informed the assessment at the preliminary examination stage’. A new Prosecutor will take over before any investigation gathers pace, adding another variable to this mix.9

For Israeli officials to be indicted for apartheid, the prosecution needs to show an intention to maintain systemic racial oppression. There is a perception that this element of intent makes it more difficult to prove than some other categories of crime. But the intentional nature of the regime is what underpins the significance of the crime of apartheid, and the concerted design and maintenance of Israel’s oppressive regime is well-documented. As a structural crime, it demands prosecution of its political architects at the highest level. Because of this, combined with ‘the racial politics of international criminal law’, there has never been a prosecution of the crime of apartheid in any court. In this sense, we see the charge of Israeli apartheid as being also an indictment of, and challenge to, international criminal law itself. If the ICC cannot bring itself to investigate and prosecute apartheid crimes in the most widely-analysed instance of apartheid since South Africa – after it has been presented with documentation and asked to do so by those subjected to the apartheid regime – that will say a lot about the politics of international criminal law.

The very fact of Palestinians submitting the claim of apartheid to an international tribunal can make its own tactical contribution to anti-colonial strategy, as global consciousness of the cold violence of Israeli apartheid continues to grow. All too often, cold violence ‘takes its time and finally gets its way’ and so, against that, a sharper focus on the strategic horizons ahead is essential. We see a place for legal contestations in that vista, though we should be under no illusions about the prospects of seeing Netanyahu and his counterparts on the stand, or the likelihood of big courtroom ‘victories’ for Palestinians. And, ultimately, the law cannot serve as a substitute for ‘what only a critical mass of people are capable of achieving’.

- Settler-decolonisation here exceeds the international legal understandings of colonialism and decolonisation that began to crystallise in the aftermath of the First World War. It evokes Indigenous Studies literatures which have clarified that land and territory remain central elements of settler-colonial domination and its unravelling. It also challenges time as a linear continuum whereby the Indigenous body stands in as a primordial figure and therefore an anachronistic possibility of becoming. Relevant works include Nick Estes, Our History Is the Future: Standing Rock Versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance (Verso, 2019); Audra Simpson, Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States (Duke University Press, 2014); Eve Tuck & K Wayne Yang, ‘Decolonization is not a Metaphor’ (2012) 1:1 Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society; Rana Barakat, ‘Lifta, the Nakba, and the Museumification of Palestine’s History’ (2018) 5:2 NAIS: Journal of the Native American and Indigenous Studies Association 1; Lana Tatour, ‘The Culturalisation of Indigeneity: the Palestinian-Bedouin of the Naqab and Indigenous Rights’ (2019) 23:10 International Journal of Human Rights 1569; Raef Zreik, ‘When Does a Settler Become a Native? (With Apologies to Mamdani)’ (2016) 23:3 Constellations 351.

- On the question of pace and priorities, according to the Prosecutor’s statement: ‘How the Office will set priorities concerning the investigation will be determined in due time, in light of the operational challenges we confront from the pandemic, the limited resources we have available to us, and our current heavy workload. … To both Palestinian and Israeli victims and affected communities, we urge patience’. On the point about appealing to Israel, the Prosecutor goes out of her way to emphasise that in the other situation previously referred to the Court regarding Israel – the Israeli military attacks on the Mavi Marmara humanitarian flotilla – she declined to pursue any charges. The statement’s references to complementarity and continuing scope for domestic investigations, as well as to the Court’s commitment ‘to investigate incriminating and exonerating circumstances equally’, also appear designed to placate specific concerns that Israel has raised previously.

- Previously this general, Itai Virob [also transliterated Veruv], was a brigade commander placed under investigation between 2009 and 2011 ‘when he admitted he encouraged his soldiers to use violence against Palestinians they were questioning’. Israel’s Military Advocate-General concluded that Virob had not been advocating ‘violence for the sake of violence’ but rather ‘violence which was necessary for the mission’. So Virob was absolved in 2011, promoted straight away by then Israeli military Chief-of-Staff, Benny Gantz, and continued to rise up the ranks. See +972 Magazine’s report here.

- Most recently, Israeli human rights organisations Yesh Din and B’Tselem have also adopted the apartheid framework – albeit based on somewhat more ‘liberal readings of Israeli apartheid’ – and international human rights organisations are expected to follow.

- Gerald Horne, Communist Front? The Civil Rights Congress, 1946–1956 (Associated University Presses, 1988) 172.

- Ibid, 167.

- Quoted in Carol Anderson, Eyes Off the Prize: The United Nations and the African American Struggle for Human Rights, 1944-1955 (CUP 2003) 210. The NAACP is the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Booker T. Washington was an early 20th century moderate Black leader who was seen by many contemporary and subsequent strands of civil rights activism as too accommodating of white supremacy.

- Even physically submitting We Charge Genocide to the UN was a debacle for the CRC. Patterson had asked WEB Du Bois and Paul Robeson to join him in Paris to present the petition to the UN General Assembly. The US government had, however, just attempted to prosecute Du Bois as a foreign agent and confiscated his passport, deterring him from travelling. The State Department also stripped Robeson of his passport – meaning he was only able ‘to deliver a copy of the petition to a “subordinate in the Secretariat’s office” in New York’ (Anderson, ibid, 194). The main consignment of copies of the petition was intercepted on route to Paris, resulting in Patterson having to bring other copies in Budapest to distribute them at the General Assembly. He then had to flee Paris himself when the US embassy tried to seize his passport and deport him. The Palestinian rights organisations’ submissions to the ICC were a more standard process, though not without their own backstory: the file containing the apartheid allegation was handed over to the Prosecutor by Al-Haq director Shawan Jabarin who Israel had previously detained without trial and then placed under travel ban for many years, and researcher Nada Kiswanson who has been subjected to repeated death threats due to her work on the ICC and Palestine.

- There has been much speculation about the potential implications of Karim Khan’s appointment as incoming Prosecutor, for the ICC generally and the Palestine investigation specifically. According to some media conjecture, ‘Israel reportedly hopes Khan may be less hostile or even cancel’ the investigation. An April 2021 letterfrom British Prime Minister Boris Johnson to the Conservative Friends of Israel group put it on record for the first time that the British government is opposed to the ICC investigation in Palestine, and also appears to claim the appointment of Khan, a British national, as a victory for Britain and its allies seeking to ‘reform’ the Court in accordance with their own agenda. The role of the Prosecutor is formally independent of any state interests, but clearly Johnson’s wording must be either a reflection of a pre-designed diplomatic initiative, or a statement of intent to mark Khan’s card.