by Michelle Ellner, published on CodePink ‘Pink Tank’ Blog, January, 2021

On December 8th, The New York Times published its celebrated “Year in Pictures” article. It showed two pictures from Venezuela, one displaying confrontation and the other despair, thus making it seem as if the country is living some kind of dystopian nightmare. As a Venezuelan-American and a photographer, I found the article disturbing. For years now, we have sadly become used to this one-sided view of Venezuela. I have come to notice that many people in the U.S. who are usually skeptical about media reporting, accept lock, stock and barrel, what they read about Venezuela. Articles fail to contextualize the problems the country faces and tend to belittle the importance, or completely ignore, any positive developments coming out of Venezuela. Thus, for instance, when I tell people that Venezuela has outperformed its neighbors by far in Covid-19 care despite U.S. sanctions and a blockade, eyebrows are frequently raised and I’m immediately told that I must have my facts wrong.

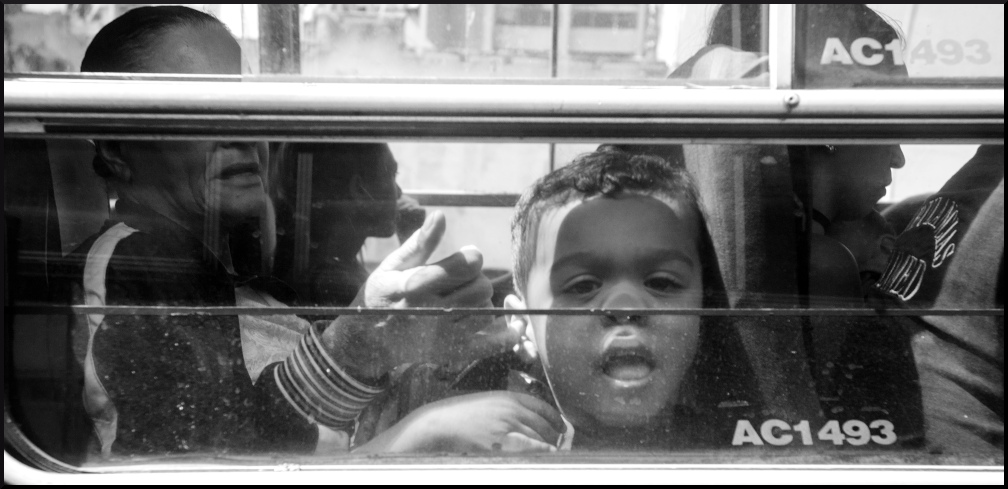

Those images that the NY Times included in the article do not portray us the way we are and always have been, as well as the way we are perceived by other Latin Americans. Venezuelans are a happy and spirited people. In spite of all the adversities, this self-image has not changed for people in Venezuela across the political spectrum. Only the most rabid opponents of the government of Nicolas Maduro think differently. I believe that most Venezuelans would be upset if they came across this misleading portrayal of their nation. So, I felt it was my obligation to write a letter to the editor of the NY Times.

I explained that par for the course, the NY Times article failed to contextualize the problems Venezuela confronts. The article in the paper, in effect, did not explain that the economic problems are derived from the US-imposed sanctions on the country. At best, the U.S. corporate media plays down the connection between the two. In contrast, an increasing number of Venezuelans, while recognizing government errors, attribute the economic difficulties in large part to Washington’s economic aggression. The polling firm Hinterlaces reported in early 2020 that 82 percent of Venezuelans oppose the sanctions. Moreover, nearly all the candidates, both pro and anti-government, who participated in the December 6 parliamentary elections firmly condemned U.S. intervention.

The media’s failure to place the sanctions at the center of the discussion of Venezuela’s economic misfortunes leaves the impression that they are something other than the overriding problem that they are. In theory, food and medical supplies are exempt from sanctions, but the reality is completely different. On 26 March, eleven U.S. Senators sent a letter to U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and U.S. Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin, in which they argued that “our sanctions regime is so broad that medical suppliers and relief organizations simply steer clear of doing business in Iran and Venezuela in fear of accidentally getting caught up in the U.S. sanctions web.” In effect, Venezuela cannot easily buy medical supplies, nor easily transport them into the country. Sanctions, even more so in times of the pandemic, are not only a collective punishment as described in both the Geneva and Hague international conventions, but it is also a crime against humanity as defined by the United Nations International Law Commission.

The article that accompanied one of the two NY Times’ photographs provided none of the necessary context. The photo that depicted anguish and suffering was followed by six paragraphs describing the nation’s “broken economy.” Not a word about the brutal U.S. sanctions.

The article’s depiction of despair and misery also lends itself to the notion of a failed state which in turn creates sympathy for regime change. In an interview with a Miami-based station on December 17, Gustavo Tarre, who represents Juan Guaidó’s parallel government in the Organization of American States, pointed to the viability of a military-political strategy, commonly referred to as “fourth-generation warfare” (4GW), which attempts to instill a psychological mindset and sensation of despair. It’s essential for U.S. policy makers that this perception not only pervades the nation, but internationally as well. Tarre indicated that his first choice is for a conventional military invasion of Venezuela, but since the time was not right for that option, the next-best one is 4GW.

After the Vietnam War, the US government understood that it was not enough to have military superiority. According to Col. John Boyd of the US Air Force, “In Vietnam we had air superiority and land superiority and sea superiority, and we lost. So, I said to myself that there is obviously something more to it.” The essence of the fourth-generation war is psychological, releasing emotions such as anxiety, fear, panic, rage and despair. The New York Times photograph piece is not a misrepresentation from a misinformed outlet, nor a well-intentioned but hastily crafted account. Regardless of intentions, the article forms part of the 4GW aimed at justifying any policy options that would promote regime change in Venezuela, by any possible means.

In short, the NY Times’s photo article reinforces the image portrayed by the mainstream media in general of Venezuelans as desperate and hopeless people without showing the other side. That is, their pride, high self-esteem, buoyancy and resilience, all of which are fitting descriptions of the Venezuelan character.

I had hoped that The New York Times would publish my letter to the editor. My hope was fed by the assumption that with a change of government in Washington, and considering the blatant failure of the Trump administration’s Venezuelan policy, the NY Times would be open to considering new perspectives. In addition, I felt assured that the NY Times, given its reputation as the nation’s preeminent newspaper, would recognize its professional and ethical obligation to clarify the misleading statements of its articles and, in this case, photos.

Indeed, instead of photos of despair and confrontation, the NY Times could have selected photos such as the ones above. The following is my unpublished Letter to the Editor of the NY Times.

To the Editor:

Last night I clicked on The New York Times’ 2020 Year In Pictures. As a Venezuelan American and a photographer, there are no words to express the sadness I felt to see that the two selected pictures of Venezuela were all about suffering and confrontation. That is just one side but there is another that should have been portrayed as well: the beautifulness that emerges from the resilience, solidarity and dignity among Venezuelans in the context of such adversity.

Moreover, in the description, there was no mention of the brutal U.S. sanctions that have not even been eased during the pandemic and are a major cause of the suffering that the pictures portray. In addition, the Trump administration’s intervention in internal politics has exacerbated the confrontations in the nation that was depicted in one of the pictures.

Michelle Ellner, CODEPINK

Michelle Ellner is a Venezuelan-American photographer and Latin America campaign coordinator with CODEPINK. Born in Venezuela, she holds a bachelor’s degree in languages and international affairs from the University La Sorbonne in Paris. She worked with community-based programs in Venezuela and served as an analyst of U.S.-Venezuela relations.