by Dali ten Hove, published on Consortium News, May 11, 2020

After six weeks of negotiations, the United States shot down hopes for a resolution to be approved in the United Nations Security Council on May 8, refusing to back worldwide ceasefires as the U.S. continues to castigate China and the World Health Organization for the Covid-19 pandemic. Meanwhile, momentum behind tenuous cease-fires is vanishing, experts say.

The long-awaited moment for the Security Council to approve a resolution supporting the UN secretary-general’s March 23 call to pause fighting in war zones during the coronavirus crisis may be gone for now. The resolution had come close to getting through, it seemed, by Thursday night, May 7, according to some diplomats.

France and Tunisia had circulated a redraft of the resolution, obtained by PassBlue, with compromise language about the WHO. The new formulation expressed support for “all relevant entities of the United Nations system, including specialized health agencies,” in obvious reference to the WHO without naming it. The organization is the UN’s only specialized health agency.

France brandished its diplomatic skills as a permanent Security Council member to get the draft put under silence procedure — a span of time allowing parties to object — until 2 P.M. Friday, Eastern Daylight Time.

Hopes were high among most Security Council members that the resolution would see the light of day by the deadline, especially because on Friday the council was holding an enormous meeting, albeit online, with an array of high-level government officials to commemorate the end of World War II in Europe.

The latest draft resolution — it has gone through numerous iterations — had overcome many obstacles laid by the U.S. and China. Estonia was the first council member to submit a draft resolution on the pandemic in early March but was swatted down mainly by China for including human-rights references, one diplomat said.

Then, a French-led draft was circulated, focusing on the global cease-fire; it was eventually merged with one led by Tunisia. That version, with more changes, was the one put under silence procedure late last week.

Around noon on Friday, May 8, silence was broken, even though several diplomats told PassBlue that senior U.S. officials had shown signs the night before that the U.S. was on board. But on Friday, Russia also said it needed more time to consider the draft; as one diplomat put it, Russia woke up and had to insert itself into the process.

In rejecting the draft, the U.S. State Department said that the Security Council should either proceed with a resolution limited to support for a ceasefire or a broadened resolution “that fully addresses the need for renewed member state commitment to transparency and accountability in the context of Covid-19.”

Guterres’s First Appeal

Back on March 23, as the world came to grips with the gravity of the spreading coronavirus, UN Secretary-General António Guterres appealed to warring parties to observe ceasefires to help fight the coronavirus by ensuring that humanitarian aid supplies could get through conflict zones. “The virus does not care about nationality or ethnicity, faction or faith. It attacks all, relentlessly,” he said. “That is why today, I am calling for an immediate global ceasefire.”

Widely viewed at first as noble but impractical, the appeal nonetheless received the backing of governments, civil society and armed groups globally. “I was surprised by the initial success of the call,” said Richard Gowan, the UN director for the International Crisis Group, a think tank in New York. He said he “was inclined to view it a little skeptically in late March, but a significant number of armed groups did respond positively. I think Guterres may have had a greater impact than he first expected.”

The UN says 16 conflict parties in Latin America, Africa, the Middle East and East Asia have declared unilateral pauses in fighting since Guterres’s appeal. This has notably included a ceasefire by Saudi Arabia in its war with the Houthi insurgents in Yemen. Nevertheless, the Houthis have not agreed to a pause, and the Saudis have been bombing Yemen during an extended cease-fire they agreed to weeks ago.

According to the Yemen Data Project, the Saudi-led coalition has carried out at least 83 air raids with up to 356 individual strikes from April 9 to April 30, the most recent information available.

Despite the early success of Guterres’s appeal, the Security Council has so far not endorsed it and remains virtually silent on Covid-19, except for issuing “press elements” — the weakest formal response it can offer publicly — when it met in a closed virtual session on April 9.

The statement that emerged from that meeting said that Security Council members “expressed their support for all efforts of the Secretary-General concerning the potential impact of COVID-19 pandemic to conflict-affected countries and recalled the need for unity and solidarity with all those affected.”

“I’m afraid that momentum is now dissipating,” Gowan said about Guterres’s appeal, as several other ceasefires declared in its wake have since broken down, including one announced in Colombia by the ELN militia, or, in English, the National Liberation Army.

“I think that a Security Council resolution supporting the call in late March or early April would have been very positive,” Gowan added. “Sadly, the council has waited too long.”

The U.S., a veto-wielding member, has strongly objected to any expression of support for the WHO in all versions of the Security Council draft resolution.

The draft by France and Tunisia backing the ceasefire appeal, circulated on April 21, said in notes, “compromise related to the language on WHO to be decided at the end of the negotiation.” China had insisted on a clause commending the organization for its efforts against the pandemic, while the U.S., which has suspended its funding of it, refused to agree to a reference to the agency. The Trump administration also pressed for addressing the origins of the new coronavirus to embarrass China, demanding that it be named the “Wuhan virus” in reference to the Chinese province where Covid-19 is believed to have originated.

The call for countries’ obligations to be transparent was also a demand by the U.S., directly challenging China. Other requirements — including lifting sanctions, by Russia and others, and exemptions of combat pertaining to counterterrorism, by the U.S. and Russia — were also overcome, according to diplomats.

The Trump administration’s denunciations of China and the WHO are widely viewed as distractions from its own sluggish response to Covid-19, as recent polling in the U.S. finds that more Americans disapprove of Trump’s handling of the pandemic. China’s posturing in favor of the WHO may in turn be meant to embarrass the U.S., Gowan said, and compensate for China’s mishandling of the coronavirus when it emerged.

“The relationship between Washington and Beijing has grown worse and worse recently,” said Jeremy Greenstock, a former British ambassador to the UN, who spoke with PassBlue from Oxfordshire, England. “It’s pathetic, really, that they are scrapping like this when they need to be cooperating.”

At a press conference on April 30, Guterres expressed disappointment about Security Council infighting in the middle of a deadly pandemic. “The relation between the major powers in the world today is very dysfunctional,” he said. “It is obvious that there is a lack of leadership.”

As Gowan said: “What’s depressing about this is that basically everyone would sign onto the cease-fire. It’s being held hostage by this WHO issue, which is sort of pathetic.”

Originally published on PassBlue, Independent UN Coverage

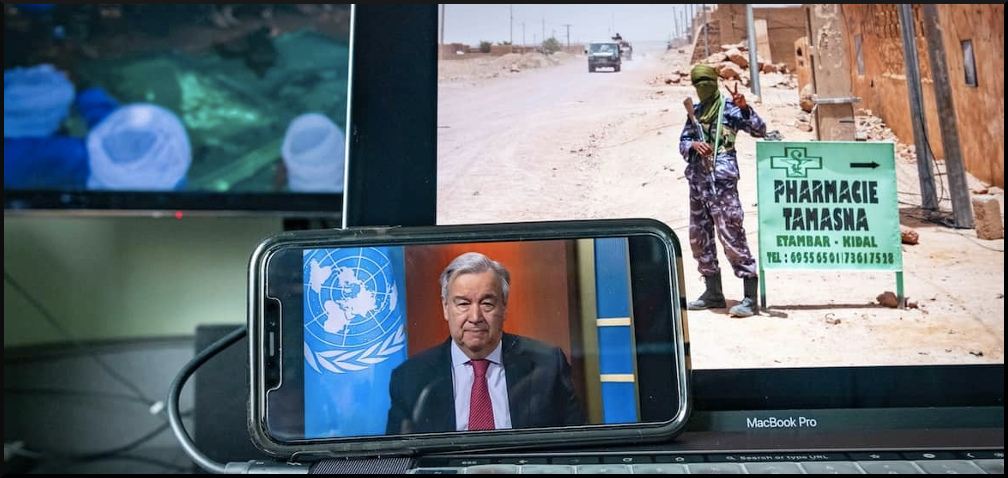

*Featured Image: Secretary-General António Guterres holds a virtual press conference to promote a report on his call for a global ceasefire during the Covid-19 outbreak, April 16, 2020. (Loey Felipe, UN photo)

Dali ten Hove is the researcher on the memoirs of former UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, “Resolved: Uniting Nations in a Divided World,” to be published in 2021. He is a general director of the United Nations Association of the Netherlands and a former trustee of the UNA-UK. He has a master’s in international relations from Oxford University.