By Daniel Lazare, Special to Consortium News, December 20, 2018

Does the Senate want Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman to own up to the murder of dissident journalist Jamal Khashoggi? Is it really seeking an end to Saudi Arabia’s war of aggression against Yemen? The answer to both questions is: kind of, sort of, not really.

That’s the takeaway from a couple of resolutions the chamber approved amid great fanfare last week. The first, sponsored by Senator Bernie Sanders, calls on Trump “to remove United States Armed Forces from hostilities in or affecting the Republic of Yemen” by, among other things, putting an end to in-flight refueling of Saudi and the United Arab Emirate war planes. The resolution, which passed 56 to 41, was a small step toward ending a war of aggression that has claimed as many as 80,000 lives – although it would have been stronger and less self-serving if it had also called for cutting off arms sales that have allowed US weapons manufacturers to reap vast profits off human misery.

But the second resolution, which passed on a unanimous voice vote, was a muddle that shows just how self-defeating US policy has become. Sponsored by Republican Senator Bob Corker, it began by holding the crown prince responsible for Khashoggi’s murder in an Istanbul consulate on Oct. 2, an act, it said, that has “undermined trust and confidence in the longstanding friendship between the United States and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.”

This generated excited headlines to the effect that the U.S. might at last be breaking with MbS, as Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman is universally known. But news outlets failed to mention what the resolution said next. It declared, for instance, that the U.S.-Saudi relationship is “an essential element of regional security.” While saying nothing about arms shipments to Saudi allies, it condemned Iran for supplying rebel forces with “advanced lethal weapons.” It blamed the Houthis “for egregious human rights abuses, including torture, use of human shields, and interference with, and diversion of, humanitarian aid shipments” – this while remaining silent about Saudi-UAE atrocities, which reportedly include a string of torture chambers in which political opponents are roasted over open fires, among other horrors.

Most bizarrely of all, the resolution warned the Saudis that “increasing purchases of military equipment from, and cooperation with, the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China challenges the strength and integrity of the long-standing military-to-military relationship” between Washington and Riyadh. The Senate is thus angry with MBS not only because he sent a seventeen-member hit squad to knock off a US resident in the middle of a European capital, but because he’s consorting with America’s business rivals. The resolution further warns that such purchases “may introduce significant national security and economic risks to both parties,” language that is every bit as threatening as it sounds.

The result is a ball of confusion, one that tries to distance the US from a murderous Saudi prince while at the same time demanding closer relations with the government he heads. It calls on the Saudis to behave more nicely to their neighbors, wind down the war in Yemen, and cease murdering people in broad daylight so that the clock can be turned back a few years and the process starts all over again. To quote Giuseppe de Lampedusa’s famous line in his novel, The Leopard, it wants everything to change so that everything can remain the same.

Incoherence

This is as incoherent as anything Trump has come up with, including his notorious Nov. 20 statement with regard to MbS’s guilt or innocence that “maybe he did and maybe he didn’t.” Trump can’t let go of his Saudi ties. But, then, the Senate can’t let go and not let go at the same time.

No one knows what to do, which is why the resolution tried to play both sides of the net. In describing MbS as “a wrecking ball,” one whom it is “very difficult to be able to do business” with, Republican Senator Lindsey Graham was essentially calling on the crown prince to step down.

He could be replaced, under U.S. pressure, perhaps with the former crown prince he replaced, Muhammad bin Nayef, said to be favored by the CIA, which publicly blamed MbS for Khashoggi’s murder.

But it could also mean a destabilizing factional feud within the ruling clan leading to a messy regime change, which, as Washington foreign-policy experts have learned all too painfully since the Arab Spring, could well lead to chaos.

To be sure, there is always the hope that a senior member of the Al-Saud will step in once MbS is removed and re-establish order. Indeed, Saudi experts already have a candidate for the job in mind: King Salman’s younger brother Ahmed bin Abdulaziz, who, while living in self-imposed exile in London, startled Saudi watchers by telling a small group of hecklers not to blame the Al-Saud for the Yemen war, only the king and crown prince. “They are responsible for crimes in Yemen,” he said. “Tell Mohammed bin Salman to stop the war.”

Since public criticism of this sort is unprecedented, it was assumed that when Prince Ahmed flew back to Riyadh a few weeks after the Khashoggi murder under a US-UK promise of protection, it was with the goal of putting the Al-Saud on a new footing.

But no one knows what might bubble up if he were to try. Things might return to normal after a royal shake-up – assuming one is in the works – or they may not. After all, it was assumed that Libya would return to normal once a former prime minister named Ali Zeidan took over from deposed strongman Muammar Gaddafi. When that didn’t work out, it was hoped that an ex-academic named Omar al-Hassi would have better luck. But when he fell too, it was clear that only anarchy would reign.

Hence the fear in Saudi Arabia is that something similar might occur post-MbS – that, as a source told The New Yorker’s Robin Wright, “[s]omeone from outside the system could make it collapse,” whereupon the kingdom would succumb to “instability like elsewhere in the region.”

Homemade in Washington

If so, it’s a problem entirely of Washington’s own making. Democratic and Republican administrations alike have continued to build up Saudi Arabia despite repeated warnings that it was creating a monster.

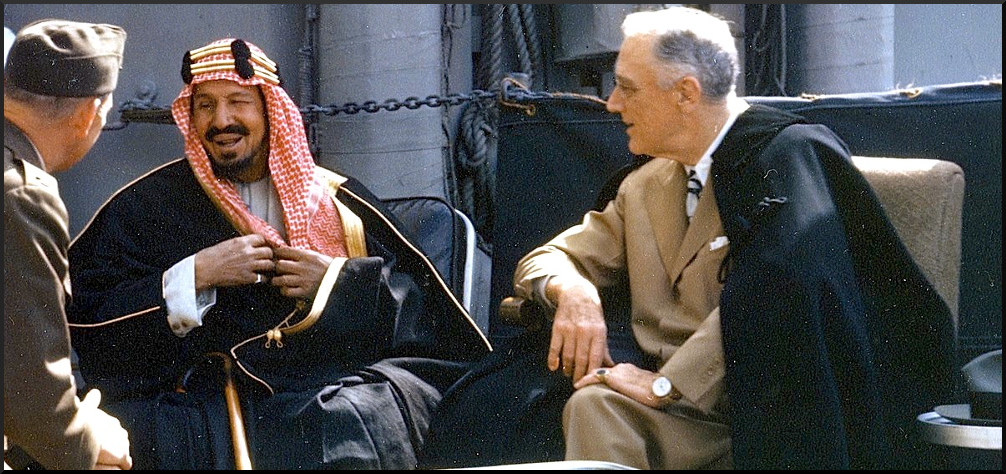

In 1945, FDR granted Saudi King Ibn Saud a blanket security guarantee in return for unrestricted oil access. A few years later, Truman used the newly-established Marshall Fund to finance massive Saudi oil shipments to war-torn western Europe, thereby establishing the kingdom as the world’s leading exporter. Following the epic price increases and Oil Embargo of the 1973, Washington hit upon yet another deal, this time to recycle excess petrodollars by exchanging Saudi oil profits for U.S. weaponry. A regional military colossus was thus born, one that felt free to attack whomever it pleased thanks to colossal oil wealth, vast quantities of high-tech arms, and an unlimited U.S. security guarantee and political cover.

Aggression and repression were the inevitable result. Unwilling to upset a vital strategic partner, the Obama administration said nothing when Riyadh sent troops into neighboring Bahrain to bloodily suppress democratic protests; when it flooded Syria with bloodthirsty Sunni jihadis, and when, in March 2015, it declared war on Yemen, its neighbor to the south. Indeed, the administration felt it had no choice but to help out.

Thus, a top general signaled his assent even while admitting that he had only been given a few hours’ notice while a State Department spokesman added forlornly: “We don’t want this to be an open-ended military campaign.” Nearly four years later, with as many as 13 million people teetering on the brink of starvation, that’s exactly what it’s turned out to be.

Joined at the hip with the Saudis, the U.S. appears to have no idea how to go about severing an increasingly toxic relationship, as last week’s incoherent Senate resolutions make clear.

The U.S. was happy to build Saudi Arabia up, but it’s clueless now that Saudi Arabia is dragging it down.

Daniel Lazare is the author ofThe Frozen Republic: How the Constitution Is Paralyzing Democracy (Harcourt Brace, 1996) and other books about American politics. He has written for a wide variety of publications from The Nation to Le Monde Diplomatique and blogs about the Constitution and related matters at Daniellazare.com.