By Ann Wright, previously published on CodePink.org and WorldBeyondWar.org

Several days ago, a journalist contacted me about a memorandum titled “Legal and human rights aspects of UNOSOM military operations” I had written in 1993, twenty-five years ago. At the time, I was the chief of the Justice Division of the United Nations Operations in Somalia (UNOSOM). I had been seconded from the U.S. Department of State to work in a United Nations Somalia position based on my earlier work in January 1993 with the U.S. military to reestablish a Somali police system in a country without a government.

The journalist’s inquiry brought to mind controversial military tactics and administration policies that have been used in the Clinton, Bush, Obama and Trump administrations that date back to the U.S./U.N. operations in Somalia twenty-five years ago.

On December 9, 1992, the last full month of his presidency, George H.W. Bush’s sent 30,000 U.S. Marines into Somalia to break open for starving Somalis the food supply lines that were controlled by Somali militias which had created massive starvation and deaths throughout the country. In February 1993, the new Clinton administration turned the humanitarian operation over to the United Nations and U.S. military were quickly withdrawn. However, in February and March, the U.N. had been able to recruit only a few countries to contribute military forces to the U.N. forces. Somali militia groups monitored the airports and seaports and determined that the U.N. had less than 5,000 military as they counted the number of aircraft taking troops and out bringing troops into Somalia. Warlords decided to attack U.N. forces while they were under strength in an attempt to force the U.N. mission to leave Somalia. Somali militia attacks increased during the Spring of 1993.

As U.S./U.N. military operations against militia forces continued in June, there was growing concern among the U.N. staff about the diversion of resources from the humanitarian mission to battle the militias and the increasing Somali civilian casualties during these military operations.

The most prominent Somali militia leader was General Mohamed Farah Aidid. Aidid was a former general and diplomat for the government of Somalia, the chairman of United Somali Congress the and later led the Somali National Alliance (SNA). Along with other armed opposition groups, General Aidid’s militia helped drive out the dictator President Mohamed Siad Barre during the Somali civil war in the early 1990s.

After U.S./U.N. forces attempted to shut down a Somali radio station, on June 5, 1993, General Aidid dramatically increased intensity of attacks on U.N. military forces when his militia ambushed Pakistani military who were part of the UN peacekeeping mission, killing 24 and wounding 44.

The U.N. Security Council responded to the attack on U.N. military with Security Council Resolution 837 that authorized “all necessary measures” to apprehend those responsible for the attack on the Pakistani military. The chief of the United Nations mission in Somalia, retired U.S. Navy Admiral Jonathan Howe, placed a $25,000 bounty on General Aided, the first time a bounty had been used by the United Nations.

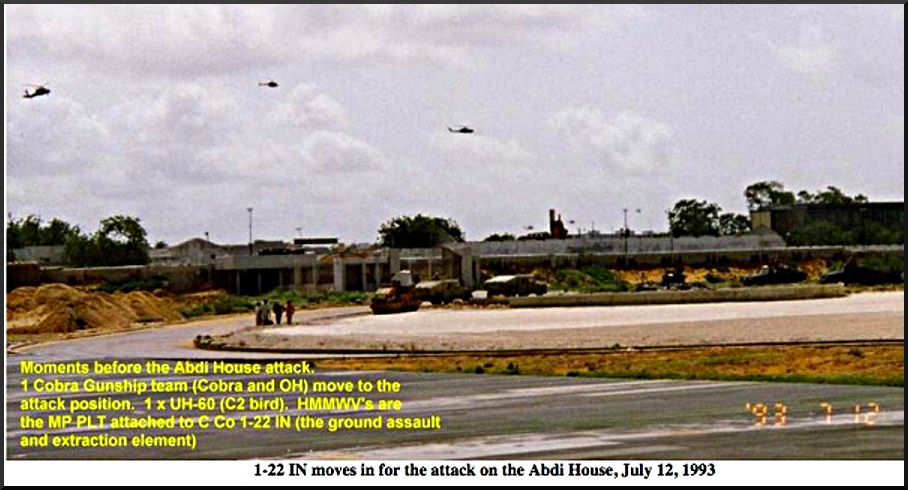

The memorandum I had written grew out of a decision to have U.S. Army helicopters blast apart a building known as the Abdi House in Mogadishu, Somalia during the hunt for General Aidid. On July 12, a unilateral U.S. military operation against General Aidid resulted in the deaths of over 60 Somalis, most of them elders who were meeting to discuss how to end the hostilities between the militias and the U.S./U.N. forces. Four journalists Dan Elton, Hos Maina, Hansi Kraus and Anthony Macharia who had gone to the scene to report on the intense U.S. military action taking place close to their hotel were killed by Somali crowds who gathered and found many of their respected elders dead.

According to the history of the 1st Battalion of the 22nd Infantry that conducted the raid, “at 1018 hours on June 12, after confirmation of the target, six Cobra helicopter gunships fired sixteen TOW missiles into the Abdi House; 30-millimeter chain guns were also used to great effect. Each of the Cobras continued to fire TOW and chain gun rounds into the house until approximately 1022 hours.” At the end of four minutes, at least 16 TOW anti-tank missiles and thousands of 20mm cannon rounds had been fired into the building. The U.S. military maintained that they had intelligence from paid informants that Aidid would be attending the meeting.

In 1982-1984, I was a U.S. Army Major an instructor of the Law of Land Warfare and the Geneva Conventions at the JFK Center for Special Warfare, Fort Bragg, North Carolina where my students were U.S. Special Forces and other Special Operations forces. From my experience teaching the international laws on the conduct of war, I was very concerned about the legal implications of the military operation at the Abdi House and the moral implications of it as I found out more of the details of the operation.

As the Chief of the UNOSOM Justice Division, wrote the memorandum expressing my concerns to the senior U.N. official in Somalia, the U.N. Secretary General’s Special Representative Jonathan Howe. I wrote:

“This UNOSOM military operation raises important legal and human rights issues from a UN perspective. The issue boils down to whether the Security Council resolutions’ directive (following the killing of the Pakistani military by Aidid’s militias) authorizing UNOSOM to ‘take all necessary measures’ against those responsible for attacks on UNOSOM forces meant for UNOSOM to use lethal force against all persons without possibility of surrender in any building suspected or known to be SNA/Aidid facilities, or did the Security Council allow that person suspected to be responsible for attacks against UNOSOM forces would have an opportunity to be detained by UNOSOM forces and explain their presence in an SNA/Aidid facility and then be judged in a neutral court of law to determine if they were responsible for attacks against UNOSOM forces or were mere occupants (temporary or permanent) of a building, suspected or known to be an SNA/Aidid facility.”

I asked whether the United Nations should target individuals and

“whether the United Nations should hold itself to a higher standard of conduct in what originally was a humanitarian mission to protect food supplies in Somalia?’ I wrote, “We believe as a matter of policy, short prior notice of a destruction of a building with humans inside must be given. From the legal, moral and human rights perspective, we counsel against conducting military operations that give no notice of attack to occupants of buildings.”

As one might suspect, the memorandum questioning the legality and morality of the military operation did not set well with the head of the U.N. mission. In fact, Admiral Howe did not speak to me again during my remaining time with UNOSOM.

However, many in relief agencies and within the U.N. system were very concerned that the helicopter attach was a disproportionate use of force and had turned the U.N. into a belligerent faction in Somalia’s civil war. Most UNOSOM senior staff members were very pleased that I had written the memo and one of them subsequently leaked it to the Washington Post where it was referenced in an August 4, 1993 article, “U.N. Report Criticizes Military Tactics of Somalia Peacekeepers.”

Much later, looking back, the military history report for the 1st Battalion of the 22ndInfantry acknowledged that the July 12 assault on the Abdi building and large loss of life based on faulty intelligence was a cause of Somali anger that resulted in substantial loss of life for the U.S. military in October 1993.

“That UN attack conducted by the First Brigade may have been the final straw that led up to the ambush of the Ranger battalion in October of 1993. As an SNA leader recounted the 12 July attacks in Bowden’s Black Hawk Down: “It was one thing for the world to intervene to feed the starving, and even for the U.N. to help Somalia form a peaceful government. But this business of sending in U.S. Rangers swooping down into their city killing and kidnapping their leaders, this was just too much”.

The 1995 Human Rights Watch report on Somalia characterized the attack on the Abdi house as a violation of human rights and a major political mistake by the UN.

“In addition to having been a violation of human rights and humanitarian law, the attack on the Abdi house was a terrible political mistake. Widely regarded as having claimed overwhelmingly civilian victims, among them advocates of reconciliation, the Abdi house attack became a symbol of the U.N.’s loss of direction in Somalia. From humanitarian champion, the U.N. was itself in the dock for what to the casual observer looked like mass murder. The United Nations, and in particular its American forces, lost much of what remained of its moral high ground. Although the report on the incident by the United Nations Justice Division rebuked UNOSOM for applying the military methods of declared war and open combat to its humanitarian mission, the report was never published. As in its reluctance to make human rights a part of its dealings with the war leaders, the peacekeepers determined to avoid a close and public examination of their own record against objective international standards.”

And indeed, the battles between U.N./U.S. forces culminated in an event that brought to an end the political will of the Clinton administration to continue military involvement in Somalia and brought me back to Somalia for the last months of the U.S. presence in Somalia.

I had returned from Somalia to the U.S. in late July 1993. In preparation for an assignment in Kyrgyzstan in Central Asia, I was in Russian language training in Arlington, Virginia on October 4, 1993 when the head of the State Department’s language school came into my classroom asking, “Which of you is Ann Wright?” When I identified myself, he told me that Richard Clarke, the director of Global Affairs for the National Security Council had called and asked that I come immediately to the White House to talk with him about something that had happened in Somalia. The director then asked if I had heard the news of a lot of U.S. casualties in Somalia today. I had not.

On October 3, 1993 U.S. Rangers and Special Forces were sent to capture two senior Aidid aides near the Olympic Hotel in Mogadishu. Two U.S. helicopters were shot down by militia forces and a third helicopter crashed as it made it back to its base. A U.S. rescue mission sent to help the downed helicopter crews was ambushed and partly destroyed requiring a second rescue mission with armored vehicles conducted by U.N forces that had not been informed of the original mission. Eighteen U.S. soldiers died on October 3, the worst single day’s combat deaths suffered by the U.S. Army since the Vietnam War.

I taxied over to the White House and met with Clarke and a junior NSC staffer Susan Rice. 18 month later Rice was appointed as the Assistant Secretary for African Affairs in the State Department and in 2009 was appointed by President Obama as U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations and then in 2013, as Obama’s National Security Advisor.

Clarke told me of the deaths of the eighteen U.S. soldiers in Mogadishu and that the Clinton administration had decided to end its involvement in Somalia—and to do so, the U.S. needed an exit strategy. He did not have to remind me that when I had come through his office in late July upon my return from Somalia, I had told him that the U.S. had never provided full funding for the programs in the UNOSOM Justice Program and that funding for the Somali police program could be used very effectively for a portion of the non-military security environment in Somalia.

Clarke then told me that the State Department had already agreed to suspend my Russian language and that I was to take a team from the Department of Justice’s International Crime and Training Program (ICITAP) back to Somalia and implement one of the recommendations from my discussions with him—creation of a police training academy for Somalia. He said we would have $15 million dollars for the program—and that I needed to have the team in Somalia by the beginning of the next week.

And so we did—by the next week, we had a 6 person team from ICITAP in Mogadishu. and by the end of 1993, the police academy opened. The U.S. ended its involvement in Somalia in mid- 1994.

What were the lessons from Somalia? Unfortunately, they are lessons not heeded in U.S. military operations in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria and Yemen.

First, the reward offered for General Aidid became a model for the bounty system used by U.S. military forces in 2001 and 2002 in Afghanistan and Pakistan for Al Qaeda operatives. Most of the persons who ended up in the U.S. prison at Guantanamo were purchased by the U.S. through this system and only 10 of the 779 persons imprisoned in Guantanamo have been prosecuted. The rest were not prosecuted and were subsequently released to their home countries or third countries because they had nothing to do with Al Qaeda and had been sold by enemies to make money.

Second, the disproportionate use of force of blowing up an entire building to kill targeted individuals has become the foundation of U.S. assassin drone program. Buildings, large wedding parties, and convoys of vehicles have been obliterated by the hellfire missiles of assassin drones. The Law of Land Warfare and the Geneva Conventions are routinely violated in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria and Yemen.

Third, never let bad intelligence stop a military operation. Of course, the military will say that they didn’t know the intelligence was bad, but one should be very suspicious of that excuse. “We thought there were weapons of mass destruction in Iraq”- it wasn’t bad intelligence but purposeful creation of intelligence to support whatever the objective of the mission was.

Not heeding the lessons of Somalia have created the perception, and in fact, the reality in the U.S. military that military operations have no legal consequences. In Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria and Yemen groups of civilians are attacked and killed with impunity and the senior leadership of the military whitewash investigations of whether the operations complied with international law. Remarkably, it is seemingly lost on senior policymakers that the lack of accountability for U.S. military operations places U.S. military personnel and U.S. facilities such as U.S. Embassies in the crosshairs of those wishing retribution for these operations.

Note: Original title of the article was: How Military Operations in Somalia 25 Years Ago Influence Operations in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria and Yemen Today

Ann Wright served 29 years in the U.S. Army/Army Reserves and retired as a Colonel. She was a U.S. diplomat in Nicaragua, Grenada, Somalia, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Sierra Leone, Micronesia, Afghanistan and Mongolia. She resigned from the U.S. government in March 2003 in opposition to the war on Iraq. She is the co-author of “Dissent: Voices of Conscience.”