SADAA, YEMEN — September is the month when students around the world head back to school and, despite enduring years of brutal war, Yemen’s children are no exception. In the Khulah School in the northern city of Sadaa, fifth-grader Saleem Ahmed Mutaher sits on the floor with about 70 other students, his mind distracted by the pain of sitting on a hard, dusty floor as well as the strong winds that enter from the classroom’s broken windows.

Ahmed Mutaher is one of millions of students in Yemen relegated to attending class inside of schools destroyed or damaged by years of incessant bombing. Once modest, yet bustling with activity and stocked with just enough to get by, Yemen’s schools have been transformed into terrifying places. Like other sectors in the country, Yemen’s system of education is deteriorating thanks to the ongoing U.S.-backed coalition’s war on the country, a conflict that shows no sign of abating.

Yemen’s Ministry of Education, based in Sanaa, estimates that the Saudi-led coalition has destroyed at least 3,000 schools and partially damaged 1,300 others. In the province of Taiz alone 371 schools have been destroyed or damaged, and in Sadaa 252 schools have suffered damage or have been destroyed as a result of the war.

A further 802 schools have been directly affected by the war, most converted into makeshift shelters to house refugees fleeing from the conflict. The report also states that 680 schools have been closed since the war began. Yemen once boasted 9,517 primary schools and 2,811 high schools. Today, the inability to pay teachers and staff combined with the systematic destruction of Yemen’s civilian infrastructure may lead to the shutdown of the country’s remaining schools.

According to the United Nations:

More than 2,500 schools are out of use; 66 percent of them damaged by airstrikes and ground fighting, 27 percent of them closed, and 7 percent used by armed groups or as shelters by displaced populations.”

Schools that have managed to remain open are at risk of being targeted by coalition bombs, caught amidst armed clashes, or closed due to the fear of disease that is now rampant in Yemen. The UN estimates that “at least 2.9 million Yemeni children have been forced out of school since the start of the war on March 26, 2015.”

Education in Yemen was not in the best of health before the war the began. A lack of equipment, unqualified teachers, and a shortage of textbooks plagued the country’s schools. Now, the ongoing Saudi-led war against Yemen has significantly accelerated the deterioration of an already struggling education system.

Bombs Outside the Classroom Window

Like many children, Saleem Ahmed Mutaher sometimes gets distracted while sitting in class. But while most children are occupied by thoughts of their peers or after-school plans, Ahmed Mutaher’s mind is filled with the pressing fear of an incoming airstrike. While some schools have remained open, they operate under the constant threat of becoming one of the routine targets of coalition airstrikes, exacting a heavy emotional toll on students and staff alike.

On August 13, 2016, students at an elementary school in northern Sadaa were targeted by two consecutive airstrikes while they were busy taking a test. Over 20 students were killed or injured in the attack. As Amnesty International has reported several times, Saudi coalition forces have routinely carried out airstrikes on schools while they were in session, disrupting or shutting down education for thousands of Yemen’s children.

Moreover, simply traveling to school has become an activity fraught with danger, as even school buses have not been immune to the torrent of coalition airstrikes. Last month the coalition targeted a school bus full of children aged six to 11 who were on a field trip in Dhahian city in northern Yemen. Forty children and 11 adults were killed in the attack. Fearing for their children’s safety, many parents have simply opted to keep their children at home this year.

Turning Dedicated Teachers Into Desperate Mercenaries

For two years, Yemen’s teachers have not received a paycheck — perhaps a minor issue to those funneling American taxpayer dollars into replenishing Saudi Arabia’s ever-expanding arsenal. The shortage of educators has led 4.5 million children to miss out on an education, as teachers are unable to eke out a living due to the ongoing war against a country with a 70 percent rate of illiteracy.

Many teachers have been displaced or are simply unable to reach their schools; and when they can, tight budgets and a dangerous environment often result in reduced teaching hours, severely undermining the quality of education.

As teacher Lutf al-Mutawakkil noted:

This job is the sole source of income for us. It would not be fair to work unpaid for numerous months while our families have no food.”

According to Yemeni Teachers Syndicate, there are some 166,000 school teachers in Yemen, many of them the sole breadwinners for their families.

Last month UNICEF reported that in Yemen, mainly in the northern provinces, 2 million children are not in school and close to 4 million others are at risk of losing access to education because about 67 percent of public school teachers across the country have not been paid for nearly two years.

Two years ago, when the war was in its infancy, state employees — including teachers — had their salaries frozen after Yemen’s Central Bank was moved to Aden, which was under the control of the Saudi coalition-backed government. At the time, al-Mutawakkil, like other teachers, was hopeful that the cessation of salaries was temporary and that coalition-backed forces in Aden would soon resume issuing paychecks to teachers and other state workers. But as time went by and teachers did their best to provide what education they could with no funding and no pay, hope began to fade. As al-Mutawakkil recounts, “before the war, I did not think that one day I would be forced to stay home with no salary.”

Before the war began, al-Mutawakkil taught at Thula City’s al-Fateh school, 50 km south of Sana’a. A graduate ot Sana’a University, the 49-year-old has been teaching for 16 years, leaving him short on both the skills and options needed to find other avenues of employment.

Like al-Mutawakkil, many teachers will not be found in their classrooms this year as they look elsewhere for a means to feed themselves and their families. Many, also like al-Mutawakkil, will resort to taking up arms and heading to the battlefield in hopes of receiving a salary from any side that is willing to pay it.

Battle, Terrorist Cells and Early Marriage Come Calling

Teachers are not the only ones whose desperation has driven them to the battlefield. As fifth-grader Ahmed Mutaher told MintPress News:

When you have a school destroyed and teachers refuse to teach you, then it becomes necessary to join the battlefield or to work.”

Ahmed Mutaher, like many school-aged children in Yemen, will likely forgo trying to get an education this year and instead either head to the front lines or seek a living elsewhere in the labor market.

Child labor in Yemen is a deeply rooted issue which was a problem well before the onset of war. In a 2013 study, the ILO, the Social Development Fund, and UNICEF reported that more than 1.3 million children were involved in child labor in Yemen.

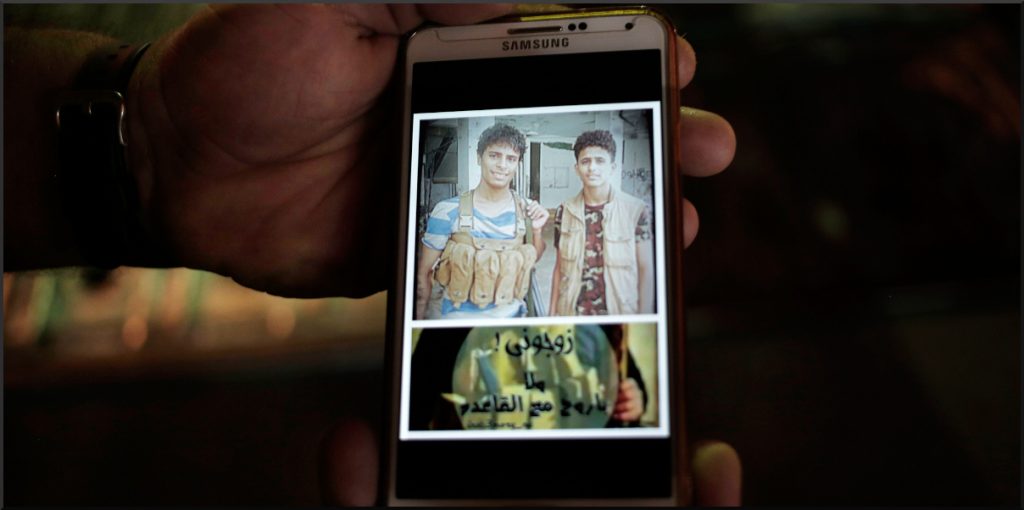

Even more alarming is the fact that al-Qaeda and ISIS have taken full advantage of the desperation to lure students who left school to join their ranks. With the rise of poverty, their unfettered access to social media, and a pool of young men with few other options, recruiting into extremist groups has become easier than ever in Yemen.

Last week, the United Nations reiterated the importance of education, warning that children who cannot go to school in a country like Yemen face a bleak future and are early targets for military recruiters. At least 2,635 boys have been recruited and are being used by armed groups across Yemen.

The lack of access to education has also pushed desperate families to dangerous alternatives, including early marriage. A 2016 survey in six governorates revealed that close to three-quarters of women were married before the age of 18 and 44.5 percent before the age of 15. Children without access to education often become illiterate and never develop the skills needed to raise successful children, transmitting poverty to the next generation.

As 16-year-old Samiah al Matri told MintPress:

Unlike my older sisters, who dropped out of school to get married, I have received a lot of support from my father, but that was before the war. Now, my father has the idea of marriage again.

Samiah’s father is a government official who — like many parents — has not received a salary and is unable to afford a private education.

Enduring Psychological Trauma

For those fortunate enough to escape death, injury or forced conscription, the haunting specter of psychological trauma still awaits.

Ebrahim AbdulKareem recounted to MintPress the toll the war has taken on his son, fourth-grader AbdulKareem.

Every night since last year, AbdulKareem wakes up in the middle of the night crying and calling out in fear as the sounds of airplanes and explosions engulf the capital and our home every night. The psychological effects of war on our son are severe.”

AbdulKareem survived an airstrike that targeted his family’s home in 2015. He lives with his family in the al-Rwadhah zone near the city’s international airport, an area that has come under severe and continuous bombardment since the war began.

As UNICEF said last month, “more than 70,000 children are receiving psychosocial support. More than 131 schools have been rehabilitated; others are currently being rehabilitated.” But, ultimately, many of Yemen’s children will carry the emotional burden of this war for the rest of their lives.

Asma Juhaff, a social worker who works with children, told MintPress:

It is rare to find a normal child, even among kindergarteners. Both at home and at school; words like surrender, warplane, shoot, enemy, kill, and Kalashnikov are often heard as children play together.”

Ahmed AbdulKareem is a Yemeni journalist. He covers the war in Yemen for MintPress News as well as local Yemeni media.