By Wayne Delucca, originally printed on Socialist Action

On Nov. 14, the Zimbabwe Defense Forces took control of the capital city, Harare. A week later, Robert Mugabe—the only leader Zimbabwe has had since independence in 1980—resigned. On the 24th, Emmerson Mnangagwa, Mugabe’s former right-hand man and until Nov. 6 the vice president, became the new president.

The coup was brewing for months. The military blocked the rise of Grace Mugabe, Robert’s second wife, who placed herself at the head of the G-40 faction in the ruling ZANU-PF party. Based on the youth wing and masterminded by education minister Jonathan Moyo, G-40 looked to move away from the traditional base, veterans of the liberation war of the 1970s.

Mnangagwa served as Mugabe’s enforcer and the head of ZANU-PF’s business empire. He is called “Crocodile” for his ruthlessness and his faction, “Lacoste,” is well represented in the officer corps and ZANU-PF’s old guard. His removal came while General Constantino Chiwenga, head of the ZDF, was on a planned visit to China. The exiled vice president, who had been trained in Beijing and Nanjing during the 1960s, joined him there. When the general returned, forces loyal to Mugabe failed to arrest him, and the coup went ahead.

Although unpopular, Grace Mugabe worked to build her legend within the cult of personality around her husband. Her followers called her “Amai” (Mother) and tried to turn a woman called “Gucci Grace” for her extravagant spending into a saintly figure. The armed forces never accepted her role and moved to keep her out of power.

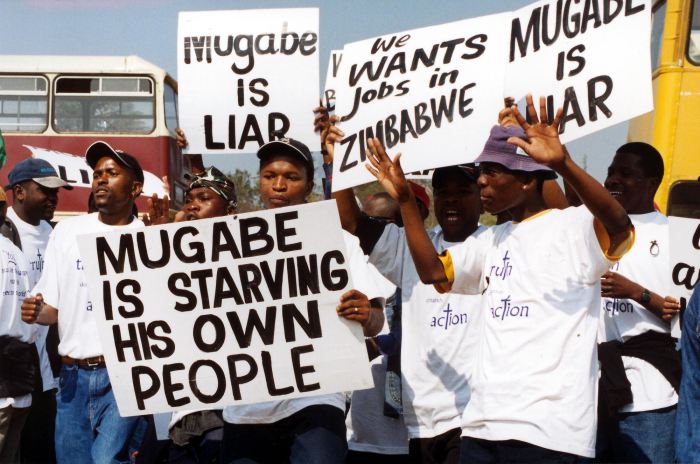

Robert Mugabe’s fall was greeted with jubilation from a country desperate for change. But Mnangagwa takes power in a deep economic crisis. The vast majority of Zimbabweans work in the informal sector, performing services or selling goods from South Africa at a high markup. He is expected to look to China and Russia for material backing and make amends with the West.

The liberation struggle and its aftermath

Robert Mugabe came to power in 1980 after a decade of war. African nationalists fought the apartheid state of Rhodesia—led by Ian Smith on behalf of a tiny white settler population. Mugabe led the China-backed ZANU-PF, which conducted most of the armed struggle. Joshua Nkomo’s ZAPU, backed by the USSR, held out for reconciliation. The British, once colonizers, brokered the peace and ensured that the new government would not expropriate white farmers for a decade. ZANU-PF won overwhelming support in the new Zimbabwe.

Robert and Grace Mugabe.

Mugabe charmed the whites and the British and appeared to be an ideal partner. He worked with international lenders such as the IMF and World Bank, and followed their advice. This meant shifting away from industrialization and toward cash crop farming. But at the same time he lashed out at his African rivals. An uprising of a few hundred die-hards was the pretext to attack the Ndebele minority who were the base of ZAPU support. From 1983 to 1987 the Fifth Brigade, trained by North Koreans, engaged in a campaign of repression known as the Gukurahundi that killed thousands of civilians. Its scars remain fresh to this day.

In the 1990s, the IMF and World Bank forced a reform package known as ESAP (scornfully nicknamed “Economic Suffering for African People”) on Zimbabwe. At first Mugabe was a model student of austerity, even as it destroyed his nation’s industrial base and made it a net importer of food.

Sharp class struggle led by the Zimbabwe Confederation of Trade Unions (ZCTU) erupted between 1996 and 1998, with mass stayaways shaking the economy. It was war veterans, protesting against rampant corruption in the fund for wounded soldiers, who forced Mugabe’s hand. He borrowed heavily to create new pensions for veterans and made them a base of support.

At the same time, Mugabe led a deeply unpopular war effort, sending troops to back Laurent Kabila in the Congo. A number of deaths caused a major embarrassment, and Mugabe’s armed forces attacked the journalists who exposed them. The war put Zimbabwe further in debt but Mugabe and his circle gained lucrative mining holdings in the Congo.

In 2000, Morgan Tsvangirai of the ZCTU led the formation of a new opposition party, the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC). It was an overly broad union of businessmen, church leaders, trade unionists, and social activists. MDC retreated from the class struggle of the 1990s while Mugabe moved left. After losing a bid for a new constitution with expanded powers, he began a campaign of land reform, taking over most of the white-owned farms. In the short term this benefited ZANU-PF members and devastated the cash crop exports, deepening the economic crisis. As time has passed, Black tobacco farmers have formed a new middle class.

Mugabe also passed an indigenization law requiring all businesses to be 51% black owned. This alienated friendly countries such as China, which had lucrative diamond mining interests. Soon afterward, Zimbabwe began to default on its debts and moved into a period of hyperinflation that would climax in 2008, when the government printed worthless $100 trillion bills.

Rise and fall of the opposition

In 2002, Mugabe won re-election in a rigged vote, and the MDC continued to grow in popularity. Tsvangirai had a clear lead in the first round of voting in 2008. Forces loyal to Mugabe, organized in part by now-President Mnangagwa, went on a campaign of terror and violence against MDC supporters. Tsvangirai stepped out of the race, allowing Mugabe to win with no opposition.

South African President Thabo Mbeki brokered an accord between ZANU-PF and MDC that led to a united government. In the power-sharing regime, the MDC proved little better than ZANU-PF. Its ministers gave themselves and party leaders large bonuses and luxury cars while most of Zimbabwe struggled to get by. By the 2013 elections, the MDC’s support had collapsed and ZANU-PF was the beneficiary.

Today the opposition is splintered. Tsvangirai, who is stricken with colon cancer, remains its face. Former finance minister Tendai Biti—who told workers that money doesn’t grow on trees while handing out $15,000 bonuses—leads the People’s Democratic Party, an MDC splinter. An older splinter, MDC-N, is led by Welshman Ncube.

Joice Mujuru, a war hero known for shooting down a Rhodesian helicopter, leads the National People’s Party. Mujuru was vice president and considered Mugabe’s heir until Grace Mugabe engineered her ouster in 2014. None of the opposition has clean hands, and the MDC was revealed in the Wikileaks cables of 2011 to have Western backing.

The crisis faced today

Zimbabwe is desperately poor; 74% of people live on less than $5.50 per day. Goods are exchanged on such a petty level that people buy a teaspoon of sugar or a squeeze of toothpaste from street hawkers. It uses the U.S. dollar as its currency and is strapped for cash. Some 70% of Zimbabweans do not have bank accounts, and have to pay 30% fees for cash from mobile pay services. Bond notes—IOUs for dollars—are likewise devalued by about 20-30% by money changers.

New President Emmerson Mnangagwa.

In 2016 the IMF called for an “internal devaluation”—cutting wages for public sector workers by 20%. Import controls staggered the informal vendors. This along with the bond notes triggered another wave of stay-aways by the unions and unrest from veterans.

International capital’s goal is to turn Zimbabwe back into a disciplined loan-payer. China and Russia are major investors in diamond and platinum mines, and believe that Mnangagwa is likely to repeal the indigenization law. He has also signaled possible restitution for white farmers, which could lead to sanctions being lifted.

Former finance minister Ignatius Chombo has been charged with defrauding the national bank, in the first reprisal against G-40 supporters. Mnangagwa has indicated that he is against violent reprisals but it is not clear how much further he will move against the deposed faction.

As of this writing, Mnangagwa has promised a new democratic era but has not named a permanent cabinet or indicated whether scheduled elections will proceed next year. Opposition leaders including Tsvangirai and Mujuru have called for a broad transitional government.

Robert Mugabe was once an electrifying freedom fighter against an apartheid regime. A self-proclaimed Marxist-Leninist, he nevertheless spent decades following the ruinous advice of imperialist creditors. His late turn to land reform and indigenization had modest results but came after decades marred by repression, corruption and kleptocracy. Mugabe’s official portraits are being taken down and street signs with his name removed even while his birthday has been made a national holiday.

When Mugabe accepted the terms offered by imperialism rather than fighting toward the revolutionary overthrow of capitalism, the fate of the national liberation struggle in Zimbabwe was sealed. It would never be allowed to be anything more than a neo-colonial state in the imperialist order. Zimbabwe, like South Africa a decade later, overthrew an apartheid regime only to see a Black-led capitalist regime come to power, which favored white settlers at home and imperialist creditors abroad.

Many revolutionary efforts, such as those in Nicaragua and El Salvador in the 1970s and ’80s, went down similar roads, and their leaders hold posts in capitalist governments doing the bidding of imperialist countries such as the United States. In contrast, the Cuban revolution overthrew capitalism; land was nationalized, health care and culture was revolutionized, and a workers’ state was created that still stands as a bulwark against capital.

But no matter how we evaluate Mugabe, it was the ruinous austerity plans imposed by the IMF and World Bank that put Zimbabwe in its present economic state. Zimbabwe is still paying debts incurred by Smith’s apartheid regime and has never recovered from the ESAP. Western institutions owe it the end of sanctions and the cancellation of all debt. Aid tied to transparent development programs would be the start of reparations for the damage done.