by Miko Peled, Published on Just World Educational, February 2019

Note: A new twist on the old adage “The best revenge is living well.” I don’t usually carry stories about religious sects but this one illustrates an important perspective on Zionism.

During a visit to Belfast a few years ago, I was taken to see a large, outdoor mural of the late IRA volunteer Bobby Sands. Next to Sands’ portrait there is a quote attributed to him which reads, “Our revenge will be the laughter of our children.”

Bobby Sands died in prison on May 5, 1981 after 66 days on hunger strike. I could hear his words ring loud when I visited the Ultra Orthodox (Haredi) community in upstate New York in early February– as I watched thousands of young Haredi Jewish children run to school in the morning.

This community was built by Hungarian Jews, survivors of Auschwitz, people determined to recreate the flourishing Jewish communities that existed in eastern Europe before the were destroyed by the Nazis.

***

The Haredi (ultra orthodox) Jewish community was nearly wiped out completely by the Nazis during World War Two. In what many in the community see as a miracle, and others might just see as plainly inexplicable, Rebbe Yoel Teitelbaum, the Rabbi Of Satmar– the city of Szatmárnémeti, Hungary which is now Satu Mare, Romania— was rescued in one of the exchange agreements made between the Zionist movement and the Nazis. (“Rebbe” is the term used for the leading Rabbi of a Hasidic community.)

When he arrived in New York after the war, so it is said, the Rebbe could not find even ten orthodox Jews with whom he could pray. Today, all these years after the Holocaust, as a result of Rabbi Yoel’s superhuman efforts, the Satmar community, a strictly observant ultra-orthodox Jewish community, is bursting at the seams.

The Rebbe’s dream was to recreate in America what was destroyed by the Nazis in Europe. Now, driving through upstate New York, county after country, town after town, one sees housing and religious and educational institutions being built faster than the blink of an eye, yet still barely fast enough to accommodate the growth of the community.

“Look at all these new homes,” Rabbi Yisroel Dovid Weiss said to me. “When I moved here these were all open spaces!”

He was taking me for a drive in his old Chevy Suburban. It was Friday, a few hours before Shabbos, the holy Jewish Sabbath, and as his custom every Friday afternoon, he was delivering flowers and gifts to people in need. We also stopped along the way to drop off a few things at the homes of his children, some of whom live in the area. He pointed out the old Yeshivas, religious schools. “They are so full they have to keep building new ones,” he said.

Young men and women of the community marry between the ages of 18-20 and within a year they start having children. “We don’t do family planning,” Rabbi Weiss tells me with a chuckle, “we have children, thank God, on an average, eight per family.” While eight might be the average, it is not uncommon to see families with ten or more children. The community lives modestly and takes care of those who are in need. A Khassuna, or wedding, for example can cost upwards of thirty thousand dollars. The community has a pool from which these expenses are paid and include all the wedding expenses as well as household goods and clothing for the newlyweds to last them a lifetime.

***

When Shabbos starts, right around sundown, Rabbi Weiss dons his special holiday clothes and his Shtreimel, a fur hat worn only on Shabbos and Yomtov, or religious holidays, and he and I head to the Shul, or synagogue. The night is dark and there are no sidewalks. As we hastily walk along the busy road we greet other Haredi Jews, all walking, some alone, some with young children: “Gut Shabbos.”

“Gut Shabbos,’ they reply, as we all rush to shul for the evening prayer.

“There is a shul on every corner,” Rabbi Weiss points out to me, “but we are going to Rabbi Beck’s shul.” Rabbi Moshe Dov Beck, has been described to me as a sage and holy man. He left Jerusalem in protest after the 1967 war. He did not want people to think he was remotely supportive of the military exploits of the Israeli army much less of the existence of the Zionist state, Israel. On the wall in the shul that is adjacent to his house is a notice the size of a large poster stating that any support for the State of Israel is sacreligious.

As we entered the shul (a little late) many people were all ready praying. Many came to greet us and say “Gut Shabbos” as we entered. Again, I thought of Bobby Sands. This is how it was in Europe for centuries, so many young Jews draped in their Talis, or prayer shawls praying with deep, deep devotion, singing at the top of their voices in a heartwarming attempt to reach the Almighty.

Rabbi Weiss pointed me to the page in the prayer book and made sure I was following along. But honestly, I found it incredibly hard to do so.

To begin with I was so taken by what I was seeing around us that I didn’t want to look down at a prayer book. I wanted to look around and take it all in. Besides, even though I could read the passages in the prayer book and understand them fully as the whole book was in Hebrew– or what the Haredi Jews call Loshen Kodesh, the holy language– I could not follow the Rabbi at the front who was praying out loud. The modern Hebrew taught in Israel is not the same Hebrew used by Haredi Jews. Their pronunciation is very different than the one the adopted by the early Zionists and so, rather than assiduously following along, again and again I found my eyes drifting away from the book to the people, particularly the young people in the room.

***

Once, I asked Rabbi Elhanan Beck, one of Rabbi Moshe Dov Beck’s sons, how he explained the growth of this community in this modern era. His answer was, “Shelo Kederech Hateva”, which can roughly be translated as “Beyond our understanding; something that can only be explained as happening by the grace and the will of The Almighty.” The mystery as I see it, is that this is a highly observant, completely segregated, and strictly religious community. In the age of freedom and the availability of practically everything and every bit of information on the internet how is it that young people opt to stay and the community continues to grow?

Rabbi Elhanan Beck lives in the Stamford Hill neighborhood of London, UK, in a community of about 30,000 ultra-orthodox Jews. Like his father, he is not only a highly respected religious leader but also a leading voice against Zionism. “I will give you 100 pounds for every Israeli flag you will find in Stamford Hill,” he tells me proudly.

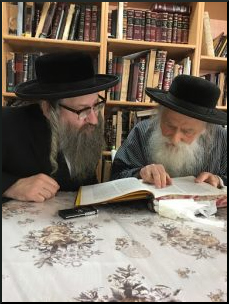

Rabbi Beck has met the UK Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn many times. Last September, he drove from London to Liverpool to stand in support of Corbyn (as shown in the photo at the head of this post), as Corbyn was facing numerous absurd accusations of anti-Semitism. The accusations, thrown at him by the Zionist groups in the UK, were due to Corbyn’s uncompromising stance on Palestine.

For people who look for the proper response to anti-Semitism, to bigotry, and especially to the Holocaust, a thriving Haredi Jewish community is precisely that answer. This is a community that has never been interested in assimilating or hiding or changing any aspect of its identity or way of life and has wanted nothing more and nothing less than to be who they are. They took no other people’s land, expelled no one, hurt not one person in order to make their dream of revival come true. Indeed, their revenge is the laughter and devotion of their children.

Miko Peled is an author and human rights activist born in Jerusalem. He is the author of “The General’s Son. Journey of an Israeli in Palestine,” and “Injustice, the Story of the Holy Land Foundation Five.”

Fantastic! Let’s have more like this to show how antiZionism is NOT antisemitism!