by Alice Speri, published on Israel-Palestine News, April 1, 2023

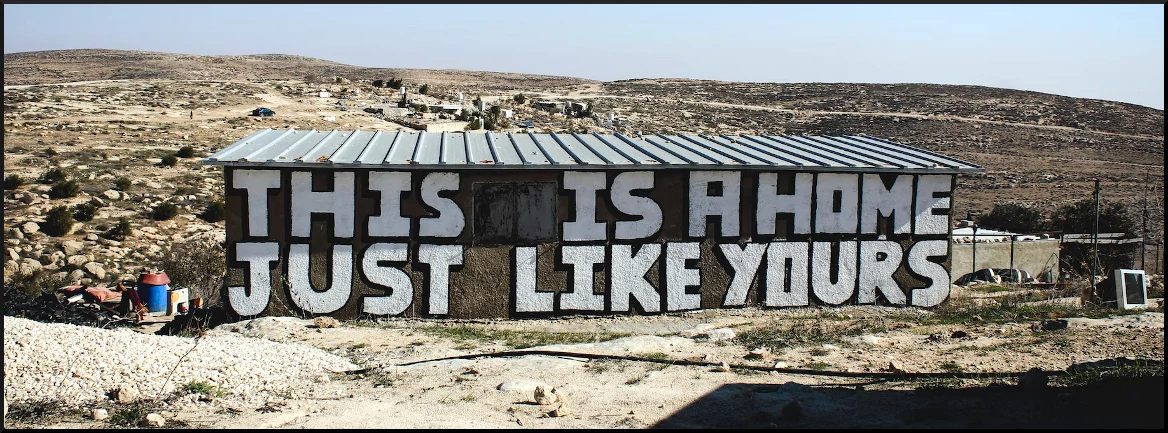

*Featured Image: A mural reads, “This is a home just like yours” in Khalet a-Daba’, a Palestinian village inside the Masafer Yatta firing zone, in the occupied West Bank on Jan. 17, 2023. (photo)

For the Palestinians living in Masafer Yatta’s firing zone, the court’s decision sanctioning their forcible transfer has exacerbated the uncertainty and fear that has dominated their lives for generations. [NOTE: read about Israeli firing zones here.]

Nasser Nawajah, a community organizer and field researcher for B’Tselem, has been living with his family in Khirbet Susya, a cluster of homes and verdant vegetable gardens near the firing zone, since the 1980s, when the village’s families were forcibly expelled from their original homes in Susya, a few hundred meters away, which Israel had declared an archaeological site.

Since then, Khirbet Susya’s residents have been living with no connection to water and electricity. When they formally applied for access to infrastructure, they were told “No, you’re illegal,” Nawajah told me, even as nearby Israeli outposts were quickly connected to infrastructure.

“At the end of the day it’s just a policy to make Palestinians’ lives miserable in all kinds of ways, firing zones, declaring buildings illegal, calling land ‘state land.’ All the roads lead to making Palestinians’ lives miserable.”

For years, residents of the area have relied on ingeniousness and the solidarity of nongovernmental organizations and activists who have provided them with a microgrid of solar panels and water tanks that the army regularly confiscates and that settlers vandalize.

Settlers also regularly damage olive trees, set fields on fire, uproot vegetables from gardens, and destroy Palestinian property.

In Khirbet Susya, Nawajah pointed to a stone monument that settlers had ripped out, a tribute to a Palestinian baby who was burnt to death along with his family in a 2015 settler attack. Not far from the village, a patch of olive trees was shriveled dry by poison. Signs in Hebrew called on people to report international peace activists to Israeli police.

Nawajah described a combination of daily harassment, increasingly violent attacks, and a seemingly endless stream of new techniques devised by settlers, under the watch of the army, to seize ever-larger swaths of Palestinian land. Sometimes, he said, settlers fly drones over herds of sheep to scare them off course; often, they send their own sheep and livestock to graze on Palestinian crops.

Army of one

A new practice was taking hold in the area, by which a lone, armed settler would set up a “pastoral outpost” on a hilltop, bringing animals to graze on the lands below — a faster and more efficient way to stake a claim on a piece of land than to set up an entire residential community.

Where residential outposts are often made up of a few caravans and makeshift homes, a pastoral outpost only requires some tools, animals, and one person who, using this tactic, can significantly alter control of the land.

“It’s enough to set up something like this to clear out a lot of land that belongs to Palestinians,” Nawajah said, noting that most Palestinian farmers would give up trying to reach that land for fear of being attacked.

During my visit to the South Hebron Hills, one such settler, a young man standing alone on a hilltop overseeing Palestinian crop lands, used binoculars to watch me, Nawajah, and a couple Israeli human rights observers. Then he approached us to ask about the purpose of our visit.

Moments later, a “civil administration” vehicle pulled up: a quiet reminder that we were in the firing zone, where the army could choose to confiscate our car at any point.

“Don’t be fooled by the word ‘civil administration,’” said Roy Yellin, B’Tselem’s director of public outreach, who was with the group that day. “It’s a part of the army that’s in charge of running the civil aspects of the life of Palestinians — but it’s the army.”

Palestinians and human rights observers stress that while the army is ubiquitous in the firing zone, it is not there to protect Palestinian land or lives: It is there to protect settlers or stand by when they attack Palestinians.

In Khirbet Susya two years ago, Palestinian residents filmed a group of adult settlers playing with the children’s toys in the village playground while soldiers watched without intervening.

(The IDF spokesperson wrote in reference to the playground incident that “the video that was published on social media represents only the beginning of the encounter and does not depict the rest of the incident in which the settlers were removed from the playground premises within minutes.”)

The army generally stands by and does little while settlers engage in violence, but sometimes the violence goes too far even for them.

In Tuba, a Palestinian village inside the firing zone near the outpost of Ma’on, settler attacks on Palestinian children have become so frequent and violent that the army now escorts the children on their way to school and back home.

“They’re not doing anything to the settlers, they just escort the children,” noted Sadot, of B’Tselem.

“This is why when we talk about settler violence, we talk about state violence, because you can’t separate it,” she added.

A systemic problem

“A lot of people will say, those settlers are a few bad apples, or something like that. But first of all, they are being allowed to live there even though it’s been declared an illegal outpost, and they get electricity and water, and the army protects them, and nobody’s getting charged when they are being violent. They have the backing of the state and they are all going for the same goal: to take over land from the Palestinians.”

Often the harassment and threats turn into open violence. Nawajah, who has been documenting dozens of such incidents for years, tells his neighbors to continue to report settler attacks to the army so as to create documentation of what happens — even as most Palestinians have given up reporting them because they fear retaliation and because they have come to view settlers and the army as one.

The IDF spokesperson wrote to The Intercept that soldiers are required to stop violations of the law by Israeli citizens, including by detaining them. “A Palestinian who was harmed as a result of an incident of violence or damage to his property can also file a complaint with the Israel Police,” the spokesperson added.

A day before I arrived, a Palestinian farmer was attacked by settlers with brass knuckles, and hospitalized. The settlers were residents of a one-family outpost, Talia Farm, named after a South African convert to Judaism who moved to the West Bank from South Africa in the 1990s, after the end of apartheid there.

“I loved apartheid,” Yaakov Talia, the outpost’s founder, once told an Israeli journalist. “I still think that apartheid is the best thing in the world.”

ABCs of occupation

In the 1990s, the Oslo Accords, with the aim of creating a Palestinian state, divided the Israeli-occupied West Bank and the Gaza Strip into different areas.

The carved-up territory would allow limited Palestinian self-governance in anticipation of an eventual state while, in a nod to Israeli security concerns, letting Israel maintain full control of much of the land.

“Area A” contains the largest Palestinian cities, where 2.8 million people live under the civil and security control of the Palestinian Authority, the home-rule body and the closest thing to a sovereign government Palestinians were ever granted.

“Area B” includes the areas immediately surrounding the cities, under Palestinian civil management and, in theory, joint Palestinian and Israeli security control.

Then there is “Area C”: the largest swath of the West Bank. In addition to encompassing all the Israeli settlements, whether urban or rural, Area C included the pastoral and agricultural land from which Palestinians have drawn their sustenance for generations, and the economic lifeline of any future state.

Covering 60 percent of what after Oslo was widely understood to be the land of a future Palestine, Area C remained under full Israeli military control, with the army frequently and increasingly making incursions into other areas as well.

Over the years, the Israeli government seized on Oslo’s unresolved parameters to deploy an intricate framework of land policies and legal justifications for taking territory that belonged to Palestinians.

Perhaps the most effective tool has been the development of settlements.

Settlement strategy

All Israeli settlements in the West Bank are illegal under international law. As part of the Oslo process, in order to preserve the possibility of Palestinian statehood, Israel committed not to change so-called facts on the ground.

That should have meant no new settlements, but Israeli officials cited what it described as natural population growth as justification to expand existing settlements, building more neighborhoods and towns in the hills surrounding existing ones, often naming each new development with a numeral next to the name of the original settlement.

In addition to those settlements, which in some cases have grown into cities fully supported by the state, more than 140 outposts have sprung up over the years. Those were built by settlers without official authorization, but while authorities occasionally issue — and rarely carry out — demolition orders against outposts, they more often provide them with electricity, water, public transportation, and army protection.

In Masafer Yatta, for instance, the rural areas surrounding Yatta have been cut off from the city by a circle of ever-expanding Israeli settlements and outposts, the latter of which are illegal not only under international law but also even under Israeli law.

Yet in several cases, outposts that were built illegally were later recognized and legitimated by Israeli authorities — as is the case of Avigail, an outpost near Masafer Yatta that the Israeli government “legalized” along with several others in February, ostensibly in response to two attacks carried out by Palestinians in east Jerusalem that month.

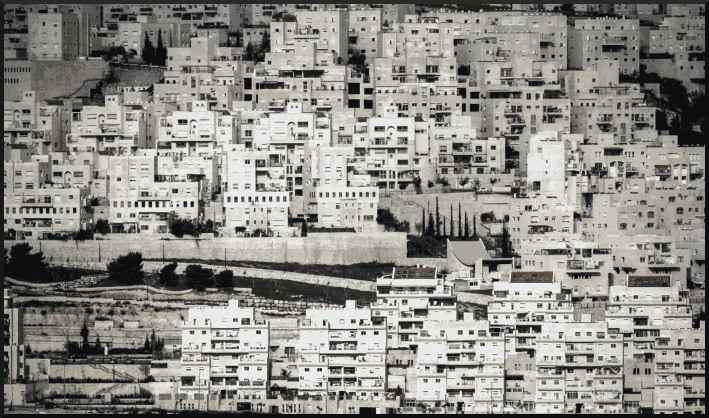

Over the years, the settlement enterprise has turned the prospect of a viable Palestinian state into a near-impossibility by precluding both territorial integrity and access to enough land to sustain a future state’s population. Settlements, usually built on hilltops, often with unnaturally narrow and long footprints so as to create a longer barrier, have not only encroached on Palestinian land: they have also effectively cut off one Palestinian community from the other.

Each settlement is also surrounded by a — usually unofficial — “security zone,” in theory a buffer between Palestinians and settlers where nobody is supposed to stand. But settlers have regularly expanded into those areas too, therefore pushing the security zone further and taking over more land.

Overall, in the West Bank, Israeli officials have confiscated more than 2 million dunams, or nearly 800 square miles of Palestinian land, more than one-third of the West Bank — much of it the private property of Palestinians. They have done so under an array of justifications, including the designation of much of it as “state land.” The Israeli group Peace Now, which tracks the expropriation of Palestinian land, estimated that the Israeli government declared up to a quarter of the West Bank state land.

“Bantustans”

B’Tselem, which also tracks Israeli land grabs, found that settlements and the roads and infrastructure that serve them have effectively encircled Palestinians in the West Bank into “165 non-contiguous ‘territorial islands’” — a fragmentation that observers have long compared to apartheid South Africa’s Bantustans.

The reference to Bantustans evokes the pockets of territory that South Africa’s apartheid government designated for Black residents, forcing their resettlement there with the goal of ultimately creating independent “homelands.” This is one of many ways in which Israel’s regime of racial domination over Palestinians has been compared to apartheid South Africa.

The references to apartheid, however, offer not only a historical comparison, but also a legal one. While the South African experience coined the term itself and popularized the concept of apartheid, the crime of apartheid has since been defined and codified in a number of international treaties, including the 1973 Apartheid Convention and the Rome Statute, the International Criminal Court’s founding document.

“Laws, policies, and statements by leading Israeli officials make plain that the objective of maintaining Jewish Israeli control over demographics, political power, and land has long guided government policy,” Human Rights Watch concluded in its 2021 report on Israeli apartheid. “In pursuit of this goal, authorities have dispossessed, confined, forcibly separated, and subjugated Palestinians by virtue of their identity to varying degrees of intensity.”

Excerpted from a lengthy article originally published on The Intercept, April 1, 2023

Another form of persecution of Palestinians breeds increasing resistance:

On The Brink: Jenin’s Rising Resistance from Mondoweiss on Vimeo.