by Richard Medhurst, published on Richard’s Substack, May 11, 2022

This article gives a useful elaboration of the way that sanctions work to undermine the economy of a targeted country and the welfare of the people who live there. Denial of fuel undermines all social services, not just personal consumption. This issue affects numerous other countries in the region, as well as in Latin America and Africa, that are suffering under U.S. Sanctions. [jb]

- Despite announcing a ceasefire on March 30th, Saudi Arabia has not lifted its siege on Yemen

- A new report exposes the shocking extent of the embargo, which was imposed in 2015, and intensified in 2021

- The Saudi-led coalition is preventing fuel ships from reaching Hodeida, Yemen’s largest port and main lifeline to 80 percent of the population

- Ships are detained by the Coalition and held for almost a year on average, causing fuel prices to rise exponentially

- Fuel ships forced to reroute to other ports are faced with new obstacles: fuel trucks must travel greater distances, increasing transportation (and thereby fuel) costs

- Trucks must go through roadblocks where armed groups such as Al Qaeda impose taxes on them; money that goes toward funding terrorism and prolonging the conflict

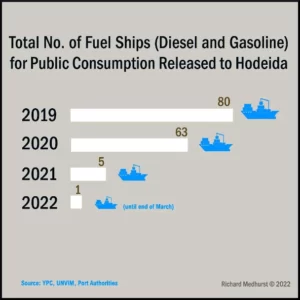

- Because of the intensified siege, fewer fuel ships are coming to Hodeida. Only one ship for public consumption has come so far in 2022

- 80 percent of Yemenis, who live in one of the poorest countries in the world, had to pay a staggering $644.4 million in additional costs last year (for gasoline and diesel products alone), due to a massive increase in fuel prices caused by the Hodeida blockade

- According to the IMF, Yemen’s inflation rate increased by an unbelievable 40 percent in 2021

- Already underfunded and at reduced capacity, hospitals are now shutting down operations due to fuel shortages. Yemenis cannot afford cooking gas, electricity, and Yemen’s agriculture, industry and service sectors are in tatters

METHODOLOGY

- This work is strictly independent, investigative journalism. All the economic data, put together by former World Bank economist Amir Althibah, is sourced from the United Nations, World Bank, International Monetary Fund (IMF), and other international organizations and open-source data.

- These sources were specifically chosen to avoid any potential accusations of bias— even if it means using deflated or conservative figures.

- Note: “Besieged Yemenis” refers to Yemenis living in areas under control of the Sana’a government, which make up the bulk (around 80 percent) of the total population.

- “YPC” refers to Yemen Petroleum Company in Sana’a, a non-profit public company that distributes fuel products local markets and population under control of the Sana’a government.

CONTEXT

This week marks 7 years since the Saudi-led coalition began its bombing campaign against Yemen, in March 2015. As a result, Yemen has become one of the poorest countries in the world.

17.4 million people— the majority of the population— are food insecure. According to UNICEF, 20 million people live in extreme poverty.

Yemen experienced one of the world’s worst cholera epidemics in recent history, with over 2.5 million cases. All the bombings, famine, disease, and destruction, have led the United Nations to describe the situation in Yemen as the world’s worst humanitarian disaster.

The majority of Yemenis live in areas controlled by the government in Sana’a, also known as the Houthis or Ansarullah. The Saudi coalition, on the other hand, supports the government in Aden which was overthrown in 2014. It is the internationally recognized government of Yemen (IRG).

In order to crush the Sana’a government, the coalition began bombing Yemen, with training and logistical support from Britain and the United States. These countries and their partners have profited immensely from the war in Yemen, selling Saudi Arabia hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of weapons.

During the rare occasions when the war in Yemen is discussed, people and media outlets mostly talk about the bombings or the famine. There is, however, another major aspect to the war that no one talks about; a silent killer that is just as bad if not worse than the bombs: the blockade.

The Saudi-led siege on Yemen prevents fuel ships from docking in the port of Hodeida, causing further damage that ripples through Yemen’s economy.

The fuel shortages and prices are so high that Yemenis cannot afford cooking gas, electricity, medicine, and the country’s inflation has skyrocketed. One of the poorest countries on earth is being forced to pay hundreds of millions of dollars extra for fuel— for absolutely no reason.

All over the world people are experiencing rises in fuel prices. Many Americans have expressed dissatisfaction with having to pay US$4 per gallon at the pump.

Currently, the blockade forces Yemenis to pay almost $9.5 per gallon ($2.5 for one liter of gasoline). This is significantly higher than what the richest nations pay for the same commodity.

The Saudi coalition claims there is no embargo on Yemen; that Yemenis are free to import food, fuel and all sorts of commodities. But the part that they leave out, is that they’re not allowing imported fuel to reach the port of Hodeida or local markets.

This report seeks to explain in fine detail exactly how the siege functions, where the additional costs come from, who is profiting from the blockade, and how it amounts to economic warfare, impacting the people that are already suffering from the world’s worst humanitarian crisis.

IMPORTING FUEL THROUGH HODEIDA

Attempting to deliver fuel to Yemen is nothing short of impossible.

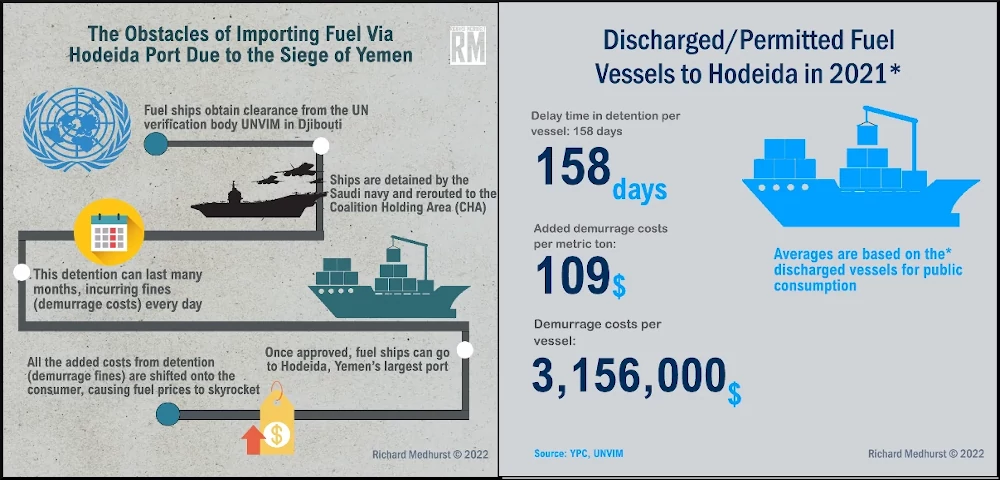

Any ship wishing to enter Yemen must first get permission from the United Nations Verification and Inspection Mechanism for Yemen (UNVIM). Ships headed to Yemen must stop in Djibouti where their cargo, place of origin, and source of funding are inspected. Once inspection and verification are completed, vessels are issued a clearance certificate by the UN, such as this:

Any ship wishing to enter Yemen must first get permission from the United Nations Verification and Inspection Mechanism for Yemen (UNVIM). Ships headed to Yemen must stop in Djibouti where their cargo, place of origin, and source of funding are inspected. Once inspection and verification are completed, vessels are issued a clearance certificate by the UN, such as this:

Despite being inspected and granted a clearance permit from the UN, once fuel ships attempt to dock at the port of Hodeida in Yemen, they are intercepted by the Saudi-coalition navy, which reroutes them to the so-called “Coalition Holding Area”, located in the Red Sea, near the coast of the Saudi city, Jizan.

In the shipping industry, when a vessel fails to discharge its cargo, the owner of the chartered ship can charge a fine. This is known as a demurrage cost.

By detaining the ships indefinitely, for months on end, their demurrage fines increase dramatically.

In 2020, UN-cleared ships going to Hodeida were detained by the Saudi coalition for a total of 4683 days. These ships paid 85 million dollars in demurrage fines— costs that are passed on to the consumers in Yemen.

In 2020, each ship coming through Hodeida paid $1.2 million in demurrage fines, on average. That number increased by 164 percent the following year, to $3.2 million per vessel.

Since 2021, the blockade has intensified, resulting in even higher fines and fuel prices

These are vessels meant for public consumption, meaning once again, that Yemenis are the ones who end up paying these costs at the fuel pump.

In 2021, ships headed to Hodeida, carrying fuel for public consumption, were detained on average for 158 days. Each vessel, on average, paid $3.2 million dollars in demurrage fines.

These long periods of detention mean:

- The price of fuel on board increases dramatically (due to higher demurrage costs)

- The lack of fuel triggers shortages, leading to higher prices for all products and services in Yemen

This domino effect can be lethal. Even Yemenis who don’t own vehicles or power generators are forced to pay higher prices for basic items, such as food and medicine.

As a result of the intensified blockade, fewer ships are coming at all.

This year in 2022, only one ship has brought fuel for public consumption to Hodeida. This steep decline in numbers can be observed below:

There are generally two kinds of fuel ships coming in to Hodeida.

- Private sector (for companies to run their factories), or UN ships. UN ships are not subject to delays.

- Public consumption (via YPC). This is fuel meant for hospitals, farmers, gas stations, civilians, etc.

What is astonishing, is that ships carrying fuel for public consumption are subject to more punitive measures.

Notice in the table below, how the ships meant for public consumption (highlighted in blue) are held by the Saudi coalition for longer, and also end up paying higher fines.

In total, two ships detained by the Saudi coalition spent over a year (438 days) in detention.

By comparison, the heaviest fines paid by a ship carrying private sector fuel was $390 thousand, compared to $3.2 million for the average paid on public sector fuel vessels. (The public sector ships are the ones that matter most—their fuel is sold at the pump, to farmers, hospitals, etc.)

To give you an example of the detention in real-time, I obtained the UN clearance permit for a fuel tanker called the “Splendour Sapphire”. It was cleared by the UN on January 3rd, 2022.

A search of the vessel on marine traffic shows that it is still in detention, almost 4 months later, near Jiz.

I received additional confirmation from a crew in the Red Sea, that despite the announcement of the Saudi “ceasefire” on March 30th, they have not been cleared to proceed to Hodeida.

This shows that people’s impression that the war is over is misguided. The siege and famine, which are the biggest killers, continue.

IMPORTING FUEL THROUGH ADEN INSTEAD OF HODEIDA

For ships that are unwilling to make the journey to Hodeida and risk being detained indefinitely, the alternative is to import fuel through non-embargoed ports such as Aden or Mukalla. These ports are under the control of the Saudi-backed government (IRG).

This poses several problems.

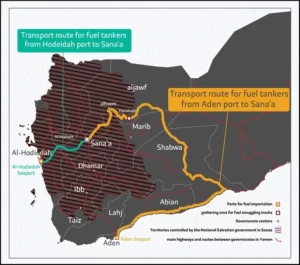

1. These ports are located far away from Sana’a and the areas where most Yemenis live. This means that fuel trucks must travel greater distances, which increases transportation and breakage costs.

Under normal circumstances, anyone importing fuel to Sana’a would never go through Aden or Mukalla because it makes no sense. They would likely go through Hodeida, because it is Yemen’s largest port and the country’s lifeline. Hodeida is close to the capital and near the bulk (80 percent) of Yemen’s population.

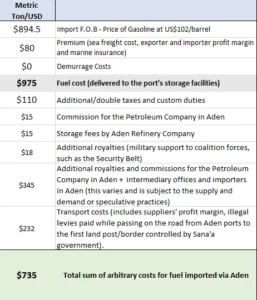

2. Ports like Aden and Mukalla are more expensive than Hodeida. Anyone attempting to import fuel through there is slapped with higher taxes and arbitrary fees. This includes a large list of things such as: customs fees, commissions to the refineries, security fees, intermediary office fees, higher transport costs, transport damages…

As an example, this ship named the “Sea-Heart” brought gasoline to Yemen last month. These are the extra fees that it had to pay by discharging at Aden:

As an example, this ship named the “Sea-Heart” brought gasoline to Yemen last month. These are the extra fees that it had to pay by discharging at Aden:

These “import duties” result in Yemenis being taxed twice for the same fuel imports: first by the Saudi-backed government (IRG), which taxes them at Aden or Mukalla, followed by another tax once the fuel trucks reach the Sana’a controlled areas.

As a result of this increased traffic, the IRG’s tax revenues on fuel imports in 2021 increased more than fourfold[1] — taxing the very population it is waging war against, with the help of the Saudi coalition.

The IRG taxes fuel imports on the basis that it is the legitimate government of Yemen. It is the internationally recognized government of Yemen at the UN and other international organizations.

It moved the central back to Aden, and took full control of Yemen’s natural resources and oil exports. As the legitimate government, however, it pays no salaries to public servants and government employees in the Sana’a-controlled areas – despite taxing the people there for their fuel imports.

ROADBLOCKS & FINANCING TERRORISM

In addition to higher import taxes, fuel trucks must travel longer and more dangerous routes, before they reach Sana’a, Hodeida, and the areas where most Yemenis live.

Fuel trucks have to take an enormous detour that extends up to 1300km (highlighted in yellow). In comparison, the journey from Hodeida to Sana’a, would be just 226km (in green).

This causes two problems:

1. It increases the cost of transportation. Trucks must travel a greater distance, increasing their fuel consumption, other incurred fees and potential breakage costs.

2. Along this alternative route, trucks are stopped by various armed groups, including Al Qaeda, who set up random roadblocks. When the fuel trucks try to pass, the militias shake them down for money. If the drivers don’t pay, they may be killed. This money often goes towards financing terrorism and prolonging the conflict.

The number of roadblocks is growing steadily as armed groups looking to make a quick buck install one checkpoint after the other, adding 5 percent to the transport cost here, another 10 percent there, another 5 percent there, etc.

The burden of both costs (higher transportation + roadblocks) is once again shifted onto the shoulders of Yemenis at the pump.

NOT ENOUGH OIL

Even if besieged Yemenis in Hodeida could somehow afford the higher prices, there isn’t enough fuel coming in.

Even if besieged Yemenis in Hodeida could somehow afford the higher prices, there isn’t enough fuel coming in.

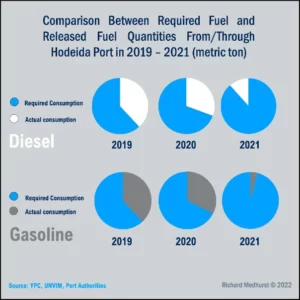

In 2020, Yemenis living in areas under control of the Sana’a government only consumed half of the gasoline and diesel that they actually needed from Hodeida port. That means a -49% deficit in consumption for 2020. The following year, the deficit reached an astonishing -90%.

THE BLACK MARKET

Like all countries impacted by siege warfare, the embargo has led to the creation of a black market.

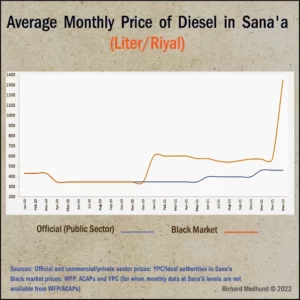

While official prices are low, there simply isn’t any oil to sell. That means consumers have to turn to the black market, where price-gouging is rampant. People are forced to pay several times more, out of necessity.

In just little over a year, from December 2020 to March 2022, the price of diesel on the black market shot up 300% (from 350/liter to 1400/liter)

Here’s the monthly average of gasoline prices in Sana’a per litter per Riyal. The same trend can be observed: black market prices continue to rise, putting unbearable pressure on Yemen’s economy and people. While the official price (in blue) is low in comparison, there is no oil to sell.

Turning to the black market means buying oil derivatives that are often of poorer quality, as they are not subject to controls and quality checks by the authorities. Yemenis not only have to pay more but end up consuming oil that is damaging to the environment, to the consumers, their property and equipment.

CONSEQUENCES OF THE SIEGE

The consequences of this blockade are absolutely blistering: Last year, Yemen’s inflation rate skyrocketed an astronomical 40%. By comparison, a country like France’s inflation rate went up a mere 1.96% in 2021.

The burden this puts on Yemeni consumers, industry and public institutions is hard to encapsulate.

Fuel shortages doesn’t just mean that people can’t drive their cars. It means no electricity, hospitals unable to function, disrupted agriculture, industry, and service sectors. The entire economy in shambles.

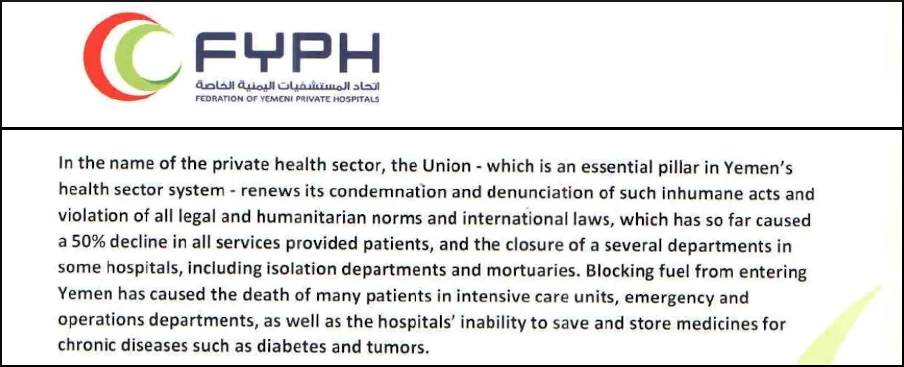

In a statement, the Federation of Yemeni Private Hospitals said that quote “blocking fuel from entering Yemen has caused the death of many patients in intensive care units, emergency and operations departments, as well as the hospitals’ inability to save and store medicines for chronic diseases…”

As a result of the siege and country’s deteriorating conditions, the United Nations raised its estimate of Yemenis that are food insecure from 13 million in December 2020, to 17 million in December 2021 (and estimated to increase 19 million by June this year). [2] Over 82 percent of the total food insecure population is living under siege, suffering from the effects of the blockade and fuel crisis.

Yemen has been under bombardment since 2015. During this time, its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has continued to shrink. Yemen’s GDP went from $957 in 2015, declining to $552 in 2017, and now sits at just $359 per person in 2020[3], making it one of the poorest countries in the world. This shows again that it is not just bombardment, but also the siege which has contributed to Yemen’s ongoing economic suffering.

As a direct result of the blockade, besieged Yemenis had to pay a staggering 644.4 million US dollars extra for fuel (diesel and gasoline) in 2021 alone; incurred costs that are entirely man-made, avoidable, and serve no purpose.

These costs are a direct result of the fuel ships being indefinitely detained, undermining the entire purpose of the UN verification; costs that are a direct result of ships being forced to dock further way, pay higher taxes to the Aden government, fuel trucks travelling greater distances, and being robbed at various checkpoints.

This siege has resulted in a decline in purchasing power of Yemeni households, who are left unable to cover basic needs, from electricity to cooking gas. In Sana’a there are zero hours of public electricity. What most people have are solar panels or private grids, the high costs of which are linked to the cost of fuel on the black market.

Based on this evidence, it is clear that the siege on Yemen is a very effective means of economic warfare.

The fuel shortages not only cause the price of fuel itself to rise, but affect everything else that depends on fuel, from food to hospitals, farming, and industry.

While most people might think that Yemenis are dying primarily from bombs, it is actually the blockade and famine that are primarily responsible for the loss of life and economic destruction.

Similar effects of siege warfare on a civilian population (through naval blockade or sanctions) can also be observed in Syria and Venezuela.

Given that the siege is the most destructive factor in the war on Yemen, Saudi Arabia’s announcement of a ceasefire— which many have misunderstood as an “end” to the war— is far from the end, as they made sure to leave the blockade in place.

Needless to say, the Coalition’s practice of detaining fuel ships on their way to Yemen undermines the entire purpose of the UN verification process in Djibouti, not to mention maritime law and Yemenis’ human rights.

Although sending aid is important, it is not a solution.

Every year, countries get together to raise money for Yemen. This year’s donor conference couldn’t even meat the stated goal, raising only $1.7b of $4.27b. Ironically, many of the top donors are the same countries responsible for the siege and bombing of Yemen.

The damage caused by the blockade is so great, that no amount of aid could remedy it. Yemen’s inflation rate has hit 40%. The price of diesel has shot up 300% on the black market in little over a year. 350,000+ Yemenis have already died, the majority of them from siege warfare, not bombs.

Theoretically, even if foreign aid were to cover all the higher fuel costs, Yemenis would still continue to suffer, because there isn’t enough fuel coming in to Hodeida to begin with, precisely because of the blockade.

The lack of fuel and higher fuel prices mean that the entire economy is in shambles. Agriculture, industry, and services cannot function, as everything comes to a grinding halt— hence the inflation rate skyrocketing.

As long as fuel ships continue to be blocked from docking at Hodeida, the crisis will only get worse. Detaining these vessels indefinitely—after they’ve already passed UN inspection—only serves to increase the total of demurrage fines.

Even the ships that don’t go through Hodeida end up being slapped with higher import duties at Aden and Mukalla ports. Then the fuel trucks have to travel greater distances, adding to transportation costs, and taking an enormous detour before reaching Sana’a and Hodeida.

And on top of all this, terrorist groups and militias stop the trucks to demand money— in what is literally highway robbery, which doesn’t only mean added costs at the fuel pump, but also funds terrorism and prolongs the conflict.

To make matters worse, the war in Ukraine is leading wheat and fuel prices to soar even higher, as Yemen imports 40% of its wheat from Russia and Ukraine.

This siege of Yemen is not only man-made, but completely preventable, illegal, causing Yemenis to suffer for no reason on an unimaginable scale. It should be lifted immediately.

*Featured Image: All graphics provided by Richard Medhurst

Richard Medhurst presents this independent, investigative journalism, in partnership with Yemeni economist Amir Althibah.

Richard Medhurst is an independent journalist. He is half English, half Syrian, and covers international politics on his YouTube channel, with over 86,000 subscribers.

Amir Althibah graduated from Oxford, worked as an economist at the World Bank for over a decade. He is based in Yemen and has over 20 years of country and international work experience in economic development.

[1] http://www.skynewsarabia.com/middle-east/1490722

[2] https://www.ipcinfo.org/ipc-country-analysis/details-map/en/c/1155480/?iso3=YEM

[3] Yemen Central Statistical Office.