by Jay Tharappel, published on The Cradle (of Civilization), August 2, 2021

From a new blog edited by Sharmine Narwani with information US people might not see otherwise by reporters who can follow Arabic News. If this is TMI re the Yemen War for you then scroll down to the section on US withdrawal.

On the one hand, I didn’t know the US had withdrawn as much support as they have from the Saudi War on Yemen. On the other, the Israeli/UAE occupation of Socotra island and some southern port cities along with the US base in Djibouti probably gives them confidence that a they can control Bab al Mandib (The straight through which oil tankers need to pass). Meanwhile, it seems like no one really matters anymore but Russia and China. [jb]

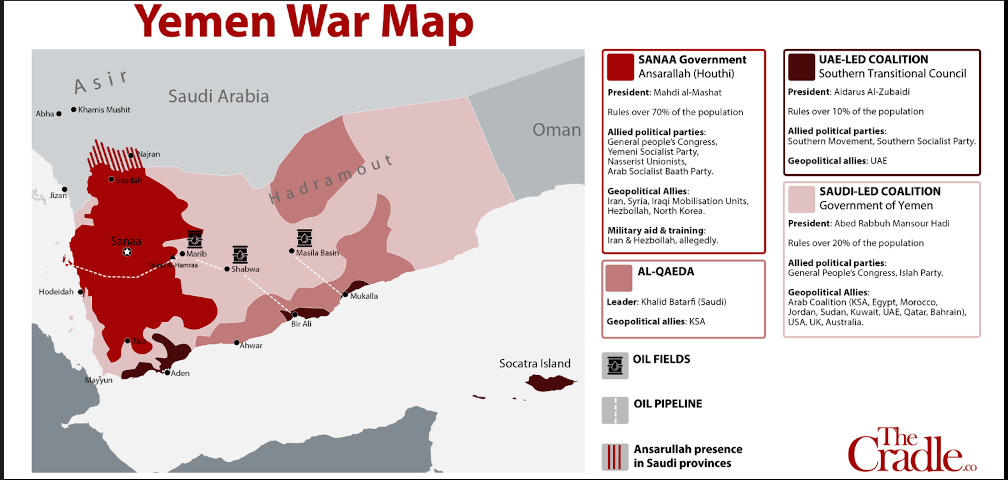

Over the past year, the Ansarallah (Houthi) backed government of Yemen, based in the capital Sanaa (the Sanaa government), has advanced on all fronts, reaching the northern gates of the Saudi-coalition held garrison-town of Marib in March this year. Marib contains Yemen’s vital oil fields, refineries, and a pipeline that could potentially distribute oil throughout the country – assets that would significantly strengthen Sanaa if they were to be captured. To make matters worse for the coalition, Houthi militia regularly penetrate deep into the officially Saudi (but historically Yemeni) provinces of Asir, Jizan, and Najran, and Sanaa’s consistent and fast-paced missile-technology advancements now have capabilities that place the oil assets of Saudi Arabia at risk of severe damage, especially under conditions of low oil prices, and growing Saudi indebtedness.

That same month, the Saudi Foreign Minister Faisal bin Farhan presented a peace initiative that was rejected by Sanaa. This, in turn, raises the question: What has changed on the ground in Yemen that has compelled the Saudis to seek out the negotiating table in earnest?

The Saudi ‘Peace Initiative’

The Saudi ‘peace initiative’ calls for a political resolution based on UN Security Council Resolution 2216, which requires the Sanaa government to hand over its weapons to the Saudis even before the partial lifting of the blockade to allow ships to dock at Hodeidah port and air traffic to enter Sanaa airport. The Sanaa government rejects these terms, taking the position that they will cease fire and negotiate only once the blockade of Yemen is lifted.

The first point of contention for Sanaa is that UN Resolution 2216 is what effectively legalized the Saudi ‘intervention’ against an entirely indigenous Yemeni political movement, namely Ansarallah, which took power in the capital Sanaa in September 2014. Ansarallah rode to power on a wave of popular discontent against the alleged corruption of the former President, Abd Rabbuh Mansour Hadi, who was perceived as serving foreign interests, especially with his IMF-advised cuts to fuel subsidies which caused inflation, and his proposal to federalize Yemen into resource-rich regions with small populations, and resource-poor regions with large populations.

Unwilling to reverse his unpopular policies, Hadi resigned as president in January 2015, before defecting to Saudi Arabia where he declared he was still the president. In November 2017, he was placed under house arrest by the Saudis, who in turn continue to claim that they’re acting on behalf of the ‘Hadi government.’

In contrast, the Sanaa government position is that those Yemeni factions that requested foreign intervention were acting against the Yemeni constitution, according to which it is treason to invite a foreign state to settle disputes with internal enemies. To quote the Deputy Foreign Minister for the Sanaa government Hussein al-Ezzi: “Under the constitution, the law and the outcomes of the national dialogue, it is not permissible to use an external party against an internal party, and whoever does so is tried for treason.”

Beneath the ‘surrender or starve’ ultimatum advanced by the Saudis, this so-called peace initiative more importantly suggests that the Saudis are trying to diplomatically stall the Sanaa government’s march on Marib. One month later (25 April), the Sanaa government annexed Talaat al-Hamra, which was the largest of the Saudi garrisons in Marib, and by 22 June, the Saudi-coalition had withdrawn their military communication network from Marib as well.

When asked about the future of Yemen in an April interview, the Saudi crown prince Mohammed bin Salman (MbS) began by pointing out that “this is not the first crisis that happens between Yemen and Saudi Arabia,” thereby implying that the Houthis represent Yemen. This implication undermines the entire premise of the intervention, which is that the Saudis would form a coalition to help Yemen defeat the Houthis, who in turn were presented as agents of Iranian aggression, despite being 100 percent Yemeni.

Enhanced Yemeni capabilities

The evolution of the Sanaa government’s military capabilities, including the use of drones, ballistic missiles, and (on special occasions) cruise missiles, have forced the Saudis to pay a heavy price for attempting to achieve their objectives.

This year alone, Sanaa has directly struck King Khalid airbase (Khamis Mushit), King Abdul Aziz military base (Dammam), Jeddah, Najran, and Abha airports, as well as Aramco facilities in Ras Tannoura, Rabegh, Yanbu, and Jizan. Faced with increasing Yemeni drone and missile attacks this year, the Saudis were compelled in April to borrow Patriot missiles from Greece.

The Sanaa government has also expanded its military presence over the internationally recognized Saudi provinces of Asir, Jizan and Najran by at least 150 thousand square kms this year, according to Sanaa-aligned media outlets like Hodhod and Yemen Press Agency which publish footage of Sanaa forces routinely assaulting Saudi military positions and taking POWs back to Yemen. These provinces were historically Yemeni before they were invaded and annexed by Saudi armies in 1934.

By March 2017, Sanaa had demonstrated that its ballistic missiles could bypass Saudi-operated Patriot air-defence systems by first smashing ‘suicide’ drones kamikaze-style into the radars of those systems. This compelled the Saudis to fire interceptor-missiles costing $4.3 million each at Yemeni drones, which cost an order of magnitude less, at around $1,000 to $5,000 each, because otherwise those drones could take out the Patriot’s radar, thereby increasing the effectiveness of an incoming Yemeni ballistic missile barrage.

This cost asymmetry was alluded to at a US Army conference in March 2017 by General David Perkins, who referred to a “very close ally of ours” (see video, 14:50) using Patriot missiles in this manner against an “adversary” without mentioning any countries by name, and further commented that “I’m not sure that’s a good economic-exchange ratio”, especially when he estimates the drones of the “adversary” cost around $200 each.

By July 2019, Sanaa had demonstrated its cruise missile capabilities according to a UN panel, after it struck Abha International Airport and the Shuqayq desalinaton plant a month earlier with its Quds missile. This raised the threat perceived by Saudi Arabia given that unlike ballistic missiles, ‘cruise’ missiles are guided and thus more accurate. It also raised the specter of Iran supplying the Sanaa government with missiles, although according to one expert, the Quds looks uniquely different from existing Iranian models, suggesting substantial ‘value-addition’ capabilities inside Yemen.

This war has witnessed “the greatest use of ballistic missile defenses of any conflict in history,” according to a June 2020 CSIS report, which goes a long way to explaining why, according to the Brookings Institute in 2017, the Saudis were spending $5-6 billion per month on Yemen-related military operations, or between $270-324 billion over the past four and a half years.

US withdrawing support for Saudi Arabia

The US is now sending clear signals to the Saudis to end the war. On 18 June, the WSJ reported that the US would be withdrawing about eight Patriot antimissile batteries from Saudi Arabia, as well as a THAAD (Terminal High Altitude Area Defense), along with the US troops manning them, which sends a clear message to the Saudis to offer more concessions to the Sanaa government.

The reason for that US military deployment was due to fears that Saudi Arabia was unable to defend its oil infrastructure in the aftermath of the brazen September 2019 operation using drones and cruise missiles that was conducted against Saudi Aramco oil facilities in Abqaiq-Khurais. Alleging Saudi incompetence, one expert, Jack Watling, opined that “the Saudis have a lot of sophisticated air defense equipment,” although “it is highly unlikely that their soldiers know how to use it,” and if that remains the case, then Saudi vulnerability to Yemeni attacks can only increase.

Although Ansarallah claimed responsibility for the operation, there are credible reasons to suggest it was launched from Iran or Iraq. Nonetheless, that the operation was intended to make the Saudis pay a price for waging war on Yemen, as now even MbS concedes, cannot be mistaken. Indeed, the Saudis did pay a price. After the operation, Aramco, slashed its total valuation by $300 billion (from $2 to $1.7 trillion), partly due to extensive infrastructure damage, but also due to the increased investment risk.

After announcing the withdrawal of its air-defence batteries, the US undermined the Saudis even further when on 25 June, the US Special Envoy to Yemen Timothy Lenderking stated that “the United States recognizes [Ansarallah] as a legitimate actor.” This is in stark contrast to the outgoing Trump administration, which in its last days in office, designated Ansarallah as a terrorist organization – a decision reversed within a month by the incoming Biden administration, citing humanitarian concerns.

Anti-Sanaa forces divided

Aside from the Sanaa government’s own efforts at resisting the Saudi-led coalition, another reason the coalition is losing is due to the corruption of their Yemeni allies, most importantly within the Islah party, or the Yemeni Muslim Brotherhood, which prior to the war, represented roughly 15 percent of parliament. Recently (28 June), pro-Islah Yemeni journalist Samir al-Nimri (based in Oman) alleged that, “the revenues of the oil exported from Shabwa, Hadramout and Marib are transferred in dollars to the National Bank of Saudi Arabia and are shared by the legitimacy of hotels officials” (emphasis added), in mockery of the Hadi government operating out of Saudi hotels.

Back in January, a UN report leaked to Reuters revealed that of the $2 billion deposited in January 2018 by the Saudis in the Aden branch of the Yemen Central Bank (YCB) for the purchase of food for Yemeni civilians, $423 million was laundered by Hadi-aligned business elites. Perhaps intending to present corruption as happening on ‘both sides’ of this conflict, the report appeared to ‘balance’ this accusation against the Hadi government with the accusation that the Sanaa government (or ‘Houthis,’ as they diminutively call it) spent $1.8 billion in tax revenues to fund its war effort, as if this were of itself controversial.

The drain of wealth from Yemen can be seen by comparing the value of the national currency in the areas controlled by the Sanaa government, to its value in the areas under Saudi–Emirati control based in Aden. On the one hand, the Sanaa government controls none of Yemen’s oil/gas reserves while drawing its strength from roughly 70–75 percent of the Yemeni population, but manages to keep the value of the riyal at 612 against the US dollar. On the other hand, the areas under Saudi–Emirati control, which share a Yemeni central bank in Aden, have all Yemen’s oil/gas reserves and between 25–30 percent of the population, but the exchange rate has reached 900 riyals to the dollar in these areas.

This is according to a report by the Sanaa-aligned National Team for Foreign Outreach (NTFO) from March, according to which, while both sides print the same currency, under Saudi-Emirati rule, the Aden Central Bank has printed “more than twice what the Central Bank in Sanaa has printed since its founding 40 years ago.” These comparisons corroborate well with the allegations from Al-Nimri of substantial outflows of US dollar earnings from Yemen to Saudi bank accounts held presumably by Hadi’s ‘hotel government.’

Uprisings against Hadi’s ‘hotel government’

These revelations of extreme corruption appear to have greatly damaged the perceived legitimacy of the Saudi-backed Hadi government in the eyes of the people it rules over (map: light pink areas). After revelations of the leaked UN report, parliamentarians aligned to the Hadi government began asking questions about the misappropriation of funds, but the Hadi-controlled YCB in Aden refused to provide any answers.

Following news of these revelations, and in the midst of rising food prices, power cuts, oil shortages, and excessive taxation, protests erupted in Aden, Taiz, Lahj, Abyan, and Mukalla demanding the resignation, arrest, and trial of Hadi-aligned governors and officials. Most memorably, in Aden on 16 March, protestors stormed the Maasheeq palace, which is the seat of power for the Hadi government.

These scandals have deepened divisions within the Islah party, with a rising faction backed by Qatar and Turkey, now accusing the dominant Saudi-backed Hadi-aligned faction (mostly living in Riyadh) of corruption, or more specifically, of “buying villas abroad while the army in Marib defends Marib without salaries.“ Indeed, the most powerful faction left standing in Taiz is now backed by Qatar and Turkey, and is commanded by Sheikh Hammoud al-Mekhlafi, who is based between Muscat and Istanbul, and whose nephew, 20-year-old Ghazwan al-Mekhlafi, currently controls key areas of Taiz.

Last month in Taiz, protestors stormed the office of Hadi-aligned General People’s Congress party (GPC) governor Nabil Shamsan, which produced documents demonstrating that the Islah–GPC administration had raised 2.3 billion riyals from the sale of qat (narcotic leaf chewed by Yemenis) but only 534 million riyals was reported, the rest plundered. It was discovered that the now exiled Shamsan administration drew incomes for 68,000 ‘fake’ recruits for the coalition’s army, that is, people who were never reporting for duty on the frontline against the Sanaa government.

Al-Qaeda reinforcements called in

When, in March, the Sanaa government called on UN bodies and member states to condemn the ongoing collaboration between the Saudi-led coalition and Al-Qaeda (AQ), the response they received was to be ignored.

That same month it was reported that Turkey would be sending AQ mercenaries from the Syrian governorate of Idlib (illegally occupied by Turkey), which was followed a few days leader by AQ leader Abdullah Muhaysini encouraging volunteers to reinforce the frontline in Marib. Following the liberation of Talaat al-Hamra, the Sanaa government claimed to have recovered ‘dozens’ of Afghan and Pakistani AQ corpses, indicating a greater reliance on foreigners.

The Saudis need inflows of foreign AQ mercenaries to shore up the Marib frontline against the Sanaa government, especially given the aforementioned revelations of Hadi government army divisions that exist only ‘on paper’, suggesting a general apathy for war. This explains why the recent (4 July) opening of a second front in Bayda against the besieged Sanaa government is being spearheaded by Al-Qaeda mercenaries getting paid monthly salaries of up to $4000 per month. For comparison, a soldier in Hadi’s army earns $100 per month, while private militias in general, such as Islahi, Southern Transitional Council (STC) and others, pay Yemenis around $350-$500 per month according to Israeli reporting from February 2019.

Importing AQa mercenaries to hold back Sanaa is not only expensive but predictably destabilizing because AQ are also allied with Islah against their common enemy, namely, the UAE-backed STC, who recently withdrew their delegation from Riyadh completely, citing a long campaign of aggression and atrocities committed against them by AQ and Islah, particularly in the struggle over Abyan. This campaign began in March when AQ launched a series of kidnappings and attacks in Abyan that killed 14 and 47 southern separatist STC militia on two separate occasions, which prompted STC politician Ali Hussein al-Bajiri to accuse his Emirati benefactors of funding AQ.

The AQ terror campaign prepared the ground for Islahi militias to seize the port of Ahwar in Abyan governorate, where boatloads of AQ mercenaries were reported to have begun arriving on 6 May. According to Saleh Junaidi, first deputy of Abyan province for the Sanaa government, “two batches of foreign extremist terrorist elements have arrived on the coast of Abyan over the past two days … coming from Syria to fight with [as in alongside] coalition militants.” This demonstrates shared interests between the Sanaa government and the STC, insofar as they both have an interest in securing Yemen’s naval borders.

Marib, missiles and money

What has changed on the ground in Yemen that compelled the Saudis to seek out the negotiating table? First, Sanaa has expanded its military capabilities, allowing for increased attacks on Saudi military sites and oil installations, thereby inflicting a grossly asymmetrical financial cost on the Saudis, one in which the Sanaa government can at very low cost, force the Saudis to bleed billions of dollars on expensive interceptor-missiles.

The Yemeni ‘drone revolution’ has been recognized globally as a major innovation in the art of asymmetric warfare. Second, with those capabilities, Sanaa has expanded their military control, both inside Yemen and over official Saudi territory, to the point where they are on the verge of liberating the oil-rich province of Marib, which could be the decisive blow that knocks Saudi Arabia out of this war, especially when its own ‘official’ territories now have a heavy Yemeni Ansarallah presence.

And third, this year’s protests and uprisings against the Saudi-backed Hadi government have exposed the corrupt Yemeni factions that are plundering Yemen’s limited natural resources while waging wars against each other over the control of those resources. The result is the failure to deploy enough soldiers to the Marib frontline, thereby forcing the Saudis into an increasing reliance on expensive AQ mercenaries.

Jay Tharappel is a PhD student at Sydney University. His research focuses on reconceptualising the concept of “imperialism” to make sense of modern wars. He blogs at The Oriental Despot.