by Jorge Martín, published on Workers World, June 14, 2021

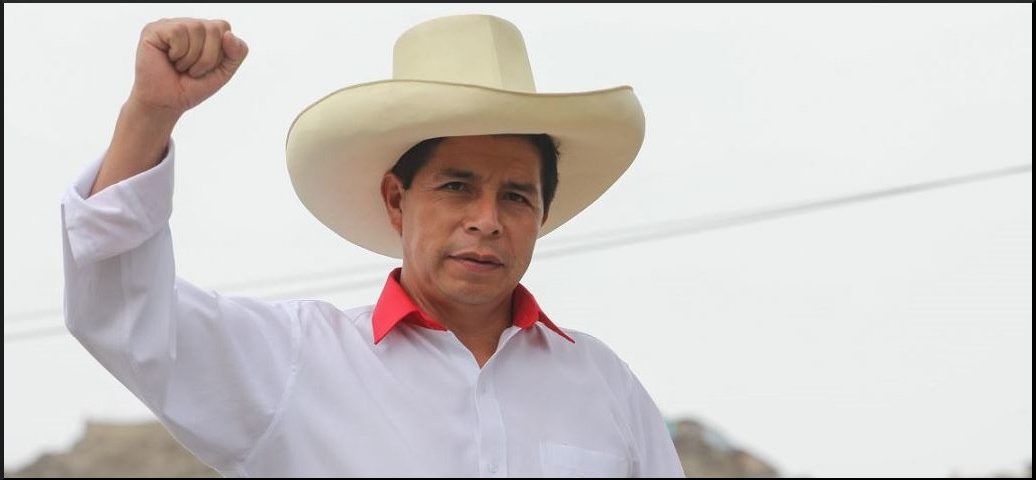

The victory of Pedro Castillo in the Peruvian presidential elections unleashed a political earthquake, reflecting the enormous social and political polarization in the Andean country. The masses have inflicted a resounding defeat upon the ruling class, thanks to the militant teachers’ union leader at the head of Peru Libre, a party that describes itself as Marxist, Leninist and Mariateguist.

[José Carlos Mariátegui (1894-1930) was the founder of the Peruvian labor and communist movements and among the most renowned Latin American Marxists of the first half of the last century.]

The recount was a slow and painful process, and the decisive result was not clear until the very end, three days after the polls closed June 6. By June 9, with 99.8% of the votes counted, Pedro Castillo has 8,735,448 votes (50.2%), giving him a small but irreversible lead over his rival, right-wing populist Keiko Fujimori, who got 8,663,684 votes (49.8%) [almost 75% voter turnout].

Official results have not yet been proclaimed. Fujimori’s team alleges fraud and is preparing dozens of appeals. The masses are ready to defend the vote in the streets. There are reports that 20,000 ronderos (members, as is Castillo, of the peasant self-defense militias created during the civil war in the 1990s) are traveling to the capital to defend the will of the people. Today, June 9, a massive demonstration has been called in Lima, where people have gathered for three nights in a row in front of Castillo’s electoral headquarters.

Castillo advanced to the final election with only 19% of the vote in the first round, due to the extreme fragmentation of [parties]. However, his electoral success is no accident. It is an expression of the deep crisis of the Peruvian regime. Decades of anti-working class privatization and liberalization policies in a country extremely rich in mineral resources have left a legacy of extreme wealth disparity and widespread corruption rotting its bourgeois democracy.

Five former presidents are in jail or accused of corruption. All the institutions of bourgeois democracy are extremely discredited. The mass demonstrations of November 2020 were an expression of the deep anger accumulated in Peruvian society.

To this must be added the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the crisis of capitalism. The country suffered one of the worst economic contractions in Latin America with an 11% drop in Gross Domestic Product. Peru has recorded the worst percentage of excess deaths and the worst mortality rate worldwide, while the wealthy and government politicians were vaccinated before anyone else.

A vote for radical change

The masses of workers and peasants want radical change, and that is precisely what Pedro Castillo represents in their eyes. His campaign had two main political pillars: the renegotiation of the terms of the contracts with the mining multinationals (and if they refuse, they would be nationalized); and the convening of a Constituent Assembly to do away with the 1993 constitution drafted during the dictatorship of Alberto Fujimori (the father of candidate Keiko Fujimori).

His main electoral slogans: “no more poor people in a rich country” and “word of the teacher” resonated with the oppressed, the workers, the poor, the peasants, the downtrodden, the Quechua and Aymara Indians, particularly in the working-class and poor areas far from Lima’s light-skinned high-class circles.

Castillo’s authority comes from having defied the union bureaucracy to lead the 2017 teachers’ strike. To the workers and peasants, he is one of their own — a humble rural teacher with peasant roots, who has vowed to live off his teacher’s salary when he assumes the presidency. His appeal is precisely that of being a leftist against the system. His popularity reveals a profound discredit of bourgeois democracy and all political parties (including the main parties of the left).

The entire Peruvian ruling class closed ranks behind Keiko Fujimori in the second round, even though she was not their favorite candidate. Her campaign was vicious. Billboards in Lima proclaimed “Communism is poverty.” The seven plagues were threatened if Castillo won the election.

He was accused of being “the candidate of the violent Shining Path” — a label that failed to stick. Nobel laureate in literature Mario Vargas Llosa, who in the past opposed Alberto Fujimori’s government from a bourgeois liberal point of view, wrote furious opinion pieces claiming that a victory for Castillo would mean the end of democracy.

Despite all that, or perhaps precisely because of the hatred he provoked among the ruling class, Castillo started the runoff campaign with a 20-point lead over his rival. That lead narrowed as election day approached. The campaign of hate pushed wavering voters towards Keiko Fujimori, but it was partly because Castillo tried to tone down his message and moderate his promises.

While in the first round he had promised to call for a Constituent Assembly at all costs, he now said he would respect the 1993 Constitution and would ask Congress (where he does not have a majority) to call for a referendum to decide whether to call for a Constituent Assembly. While in the first round he said he would nationalize the mines, he later emphasized that he would first try to renegotiate the contracts. The more he did that, the more his lead shrunk, to a point where on election day his victory was very narrow.

Class contradictions

However, the narrow victory masks the country’s acute class polarization. Fujimori won in Lima (65 to 34), and even here, her best results are in the richest districts: San Isidro (88%); Miraflores (84%); and Surco (82%). Castillo has won in 17 of the country’s 25 provinces, with massive victories in the poorer Andean and southern regions: Ayacucho 82%; Huancavelica 85%; Puno 89%; Cusco 83%. He also won in his native Cajamarca (71%), a region where there have been massive protests against mining.

In the final days of the campaign, Keiko Fujimori, in classic populist style, promised direct transfers of money from mining company profits to the people of the towns where the mines are located. This was an attempt to turn voters away from Castillo’s proposal to change the contracts to benefit all the people. Voters elected Castillo massively in all mining towns: in Chumbivilcas (Cusco), 96%; Cotabambas (Apurimac), the base of the Chinese mine MMG Las Bambas, over 91%; Espinar (Cusco), where Glencore operates, over 92%; Huari (Ancash) where there is a joint BHP Billiton — Glencore mine, over 80%.

The masses of workers and peasants supporting Castillo were ready to take to the streets to defend his victory, while Fujimori shouted fraud and then appealed the results. In the days leading up to the elections and immediately after, there have been rumors of a military coup. Prominent Fujimori supporters called on the army to intervene to prevent Castillo from taking power.

There is no doubt that a sector of the ruling class in Peru is in panic and used every means at their disposal to prevent Castillo from winning the elections. They see him as a threat to their power and privileges and the way they have governed the country since its independence 200 years ago.

So far, it appears that the more cautious elements of the ruling class have prevailed. An editorial in the leading bourgeois newspaper La Republica described Fujimori as irresponsible for crying fraud. “Let us appeal to the sensible and thoughtful leadership of political leaders and authorities. We need to calm the streets in the interior of the country, which are seething with distrust and weariness.” That is what worries them. Any attempt to steal the election from Castillo would bring the masses of workers and peasants to the streets, radicalizing them all the more.

All this gives an idea of what Castillo will face once he takes office. The ruling class and imperialism will resort to any means necessary to prevent him from actually governing. We have seen the same script in the past against Chávez in Venezuela.

Prominent members of the Venezuelan opposition coup were in Lima to support Fujimori before the elections, and that is no accident. They will use Congress and the other bourgeois institutions, the media, the state apparatus (up to and including the army) and economic sabotage, to limit Castillo’s ability to implement his policies.

Defend victory: prepare for battle

Castillo’s program, despite references to Marx, Lenin and Mariátegui in Peru Libre documents, is one of capitalist national development. He proposes to use the country’s mineral wealth for social programs (mainly education) and to work with “productive national entrepreneurs” to “develop the economy.” His models are Rafael Correa of Ecuador and Evo Morales of Bolivia.

The problem is that these so-called responsible “national productive” capitalists do not exist. The Peruvian ruling class, the bankers, landowners and capitalists are closely linked to the interests of the multinationals and imperialism. They are not interested in any “national development,” but only in their own enrichment.

Castillo will now face a dilemma. On the one hand, he can govern in favor of the masses of workers and peasants who have elected him, which would mean a radical break with the capitalists and the multinationals. That can only be accomplished through carrying out a mass mobilization outside the electoral arena.

Or Castillo can give in, soften his program and adapt to the interests of the ruling class, which means he will be discredited among those who voted for him, paving the way for his own downfall. If he tries to serve two masters (the workers and the capitalists) at the same time, he will please neither.

In an attempt to reassure “the markets,” which were nervous during the count, Castillo’s team issued a statement worth quoting in depth:

“In an eventual government of Professor Pedro Castillo Terrones, Peru Libre’s presidential candidate, we will respect the autonomy of the Central Reserve Bank, which has done a good job keeping inflation low for more than two decades. We reiterate that we have not considered in our economic plan nationalizations, expropriations, confiscations of savings, exchange controls, price controls or import prohibitions. The popular economy with markets that we advocate promotes the growth of companies and businesses, particularly agriculture and SMEs, in order to generate more jobs and better economic opportunities for all Peruvians. We will maintain an open and broad dialogue with the various sectors of honest businessmen and entrepreneurs, whose role in industrialization and productive development is fundamental. Guaranteeing the right to health and education for all requires improving quality and increasing social spending, which must be based on mining-tax reforms to increase collection within the framework of a fiscal sustainability policy, with a gradual reduction of the public deficit and respecting all commitments to pay the Peruvian public debt.” (emphasis Martin)

Castillo himself declared:

“I have just had conversations with the national businessmen, who are showing their support to the people. We will create a government respectful of democracy, of the current Constitution. We will have a government with financial and economic stability.”

All experience shows that what the ruling class describes as “financial and economic stability,” in reality means making the workers and the poor pay for the crisis of their system by guaranteeing the best possible conditions for the realization of capitalist profits.

The payment of the debt is in direct contradiction with implementing of a policy of social spending. Castillo should oppose this concession and act in support of the general interests of the workers and peasants. There is no middle road.

For now, the Peruvian masses celebrate and remain on guard to defend their victory. The struggle has just begun. Every step forward taken by Castillo must be supported. His vacillations or retreats must be criticized. The workers and peasants can only rely on their own forces, and these must be mobilized to strike blows against the oligarchy.

Mariátegui, in the conclusion of his “Anti-imperialist Point of View,” a thesis he presented to the Latin American Conference of Communist Parties in 1929, said:

“In conclusion, we are anti-imperialists because we are Marxists, because we are revolutionaries, because we oppose capitalism to socialism as an antagonistic system, called to succeed it, because in the struggle against foreign imperialisms we fulfill our duties of solidarity with the revolutionary masses of Europe.”

His point of view is today more relevant than ever.

*Featured Image: OjoPúblico.com

Published in rebelion.org, June 10. Translation by Michael Otto