by Manlio Dinucci, published on Workers World, March 19, 2021

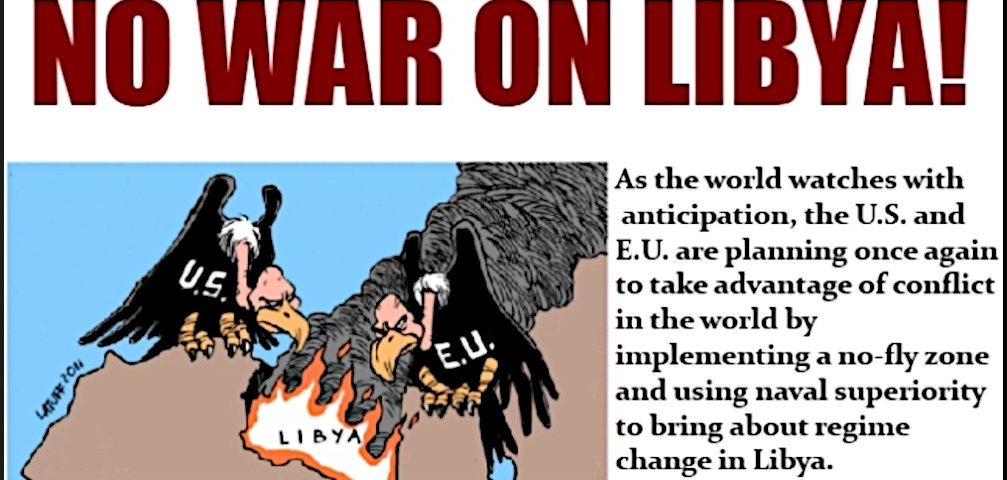

Ten years ago, on March 19, 2011, U.S.-NATO forces began the air and sea bombardment of Libya. The war was directed by the United States, first through its Africa Command, then through NATO under U.S. command. In seven months, the U.S.-NATO air force carried out 30,000 sorties, 10,000 of which were bombing attacks, unleashing over 40,000 bombs and missiles.

Italy, with the multi-party consensus of the Parliament (its Democratic Party in the lead), participated in the war using seven air bases (Trapani, Gioia del Colle, Sigonella, Decimomannu, Aviano, Amendola and Pantelleria), with Tornado fighter-bombers, Eurofighters and others, plus the aircraft carrier Garibaldi and other warships.

Before the air-sea offensive began, U.S.-NATO agents and client states financed and armed ethnic groups and reactionary Islamic groups hostile to Libya’s government, and Qatar deployed special forces to instigate armed clashes within the country.

In this way, the African country was demolished. Libya, as the World Bank documented in 2010, had maintained “high levels of economic growth,” with its GDP increasing by 7.5 percent per year, and recorded “high human development indicators,” including universal access to primary and secondary education and, for over 40 percent of the youth, access to university education. Despite the disparities, the average standard of living in Libya was higher than in other African countries. About two million immigrants, mostly African, found work there.

The Libyan state, which possessed the largest oil reserves in Africa plus others of natural gas, had limited profit margins for foreign companies. Thanks to energy exports, the Libyan balance of trade showed a positive margin of $27 billion per year. With these resources, the Libyan state had invested around $150 billion abroad.

Libyan investments were crucial

Libyan investments in Africa were crucial to the African Union’s plan to create three financial bodies: the African Monetary Fund, with headquarters in Yaoundé, Cameroon; the African Central Bank, with headquarters in Abuja, Nigeria; and the African Investment Bank, with headquarters in Tripoli, Libya. These bodies would have served to create a common market and a single African currency.

Libyan investments in Africa were crucial to the African Union’s plan to create three financial bodies: the African Monetary Fund, with headquarters in Yaoundé, Cameroon; the African Central Bank, with headquarters in Abuja, Nigeria; and the African Investment Bank, with headquarters in Tripoli, Libya. These bodies would have served to create a common market and a single African currency.

It is no coincidence that the NATO war to demolish the Libyan state began less than two months after the African Union summit of Jan. 31, 2011. This summit gave the go-ahead for the creation of the African Monetary Fund by the end of 2011.

This is proven by emails of the Obama administration’s Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, later brought to light by WikiLeaks. The United States and France wanted to eliminate [Libyan leader Muammar] Gaddafi before he could use Libya’s gold reserves to create a pan-African currency as an alternative to the dollar and the CFA franc (the currency imposed by France on 14 of its former colonies).

The proof: Before the bombers went into action in 2011, the banks went into action and seized the $150 billion invested abroad by the Libyan government, most of which disappeared. Goldman Sachs, the most powerful U.S. investment bank, of which Mario Draghi has been vice-president, was prominent in the great robbery.

Today in Libya power groups and the transnational corporations hoard the revenues from energy exports, in a chaotic situation with regular armed clashes. The standard of living of the majority of the population has plummeted.

African immigrants, whom the armed bodies running Libya charged with being “Gaddafi’s mercenaries,” have even been imprisoned in zoo cages, tortured and murdered. Libya remains in the hands of human traffickers. It has become the main transit route of a chaotic migratory flow towards Europe that has caused many more victims than the war of 2011.

In the town of Tawergha near the city of Misurata, Libya, the NATO-backed reactionary Islamic militias of Misurata (those who murdered Gaddafi in October 2011) have carried out a real ethnic cleansing, forcing almost 50,000 Libyan citizens to flee and refusing to allow them to return.

The Italian Parliament also has responsibility for this. On March 18, 2011, it committed the government to “take any initiative” (i.e., Italy’s entry into war against Libya) “to ensure the protection of the people of the region.”

Dinucci’s article was first published in the Italian web daily newspaper Il Manifesto on March 16. Translation into English by John Catalinotto.