Five years after the murder of Michael Brown, the people have achieved an apparent victory: the indictment, conviction and impending imprisonment of a white police officer for the murder of an unarmed Black man.

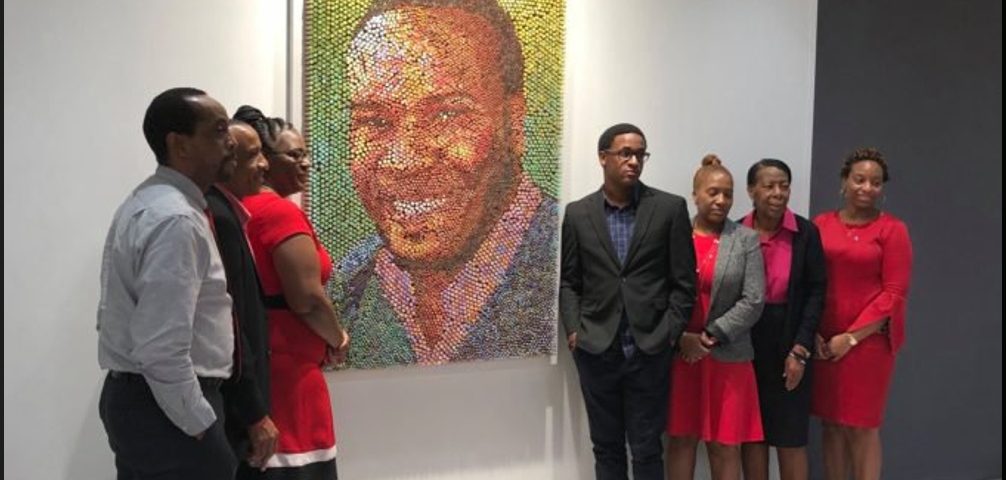

Botham Jean, 26 years old, was gunned down in his own apartment in Dallas, Texas, by Dallas Police Officer Amber Guyger on Sept. 6, 2018. Guyger, who lived directly beneath Botham, claimed she went to the wrong floor at the end of a 13-hour shift, entered Botham’s apartment believing it was her own and shot Botham believing he was an intruder.

Locally and nationally, Black Lives Matter organizers demanded that Guyger be punished, whether or not her improbable story was true. It’s exceedingly rare that a police officer is punished for murder, especially when the victim is Black. Given the incredibly lenient standards police officers face in the aftermath of a shooting, it’s surprising that Guyger was indicted at all, and even given a 10-year sentence.

It’s true that it is particularly hard to justify the quick resort to deadly force shown by Guyger or the absurdity of killing him in his own home. But Guyger is not unique among police officers in showing a willingness to shoot first and ask questions later.

On Nov. 22, 2014, 12-year-old African American Tamir Rice was gunned down by a white Cleveland police officer, while playing with a toy gun in a public park. The police officer didn’t even wait until he was out of his car to open fire. Nor is Guyger the first off-duty officer to murder an innocent person. Such occurrences are disturbingly common and seldom result in criminal prosecution.

A common failing of liberal commentators is the attempt to explain police killings, and the reaction to them by the justice system in legalistic terms. But laws exist to serve those who write them and will be twisted against the oppressed at a moment’s notice. An oppressor cannot be adequately described with their own propaganda. This conviction should be understood in the wider context of the Black struggle against police violence.

It is about the relations of power between the ruling class and the working class — particularly the nationally oppressed. The current iteration of the Black Liberation struggle, in the form of Black Lives Matter, has been raging off and on for over five years. It erupted into the national consciousness during the uprising in Ferguson, Mo., following Michael Brown’s death. Since then, there have been dramatic high points and quiet lows, but the movement refuses to abate.

Chinks in the armor of the state

Through it all, the repressive state has remained firm. The capitalist ruling class, with its political legitimacy waning, desperately needs to hold on to its monopoly of force. Police officers must be permitted to kill without fear of consequence. Without that power imbalance between the state and the working class, the ruling class’s hold on power would quickly erode. This is the reason why so many egregious cases of police violence have gone unpunished.

Nevertheless, individual agents of the state are not immune from public pressure. The insistence of Black activists to continue to struggle, and even to escalate their tactics, must weigh on the minds of prosecutors, police and politicians everywhere. Any police shooting has the potential to trigger a mass uprising.

As Malcolm X said, the U.S. is a “racial powder keg” of tension. No mayor of any city wants to preside over the collapse of civil order. These agents of the state, therefore, must be hyper-aware of rising tensions across the U.S. They no doubt followed the protests on the recent anniversary of Eric Garner’s killing — a struggle that has persisted for five years — and the decision of local activists to march to the home of his murderer, Daniel Pantaleo, who was eventually fired.

Likewise, in Dallas the Botham Jean case threatened to raise tensions to a fever pitch. Just days after the killing, nine activists were arrested for obstructing traffic during a Dallas Cowboys football game. And when those activists remained in jail for several days — more time behind bars than Guyger has yet seen — further protests broke out to demand their release.

Dallas is also where five police officers were killed in July 2016, and nine others wounded, by Micah Johnson — seemingly in reaction to the surge of police killings at that time. This is what Malcolm’s powder keg looks like when the fuse gets too short.

In order to maintain power, the capitalist ruling class and their state agents are motivated to remain firm in the face of liberal demands for reform. And yet, they must weigh that policy against sporadic but determined unrest — and the threat of full-blown uprisings — by the most militant forces in the Black struggle. The conviction of Amber Guyger is a result of that contradiction giving way in favor of the people.

While this conviction cannot be viewed as the start of a major sea change, it shows the power of nationally oppressed peoples within the U.S. working class. There will no doubt be further outrages from the police and attacks by white supremacists. But this event should serve as a signal that the ruling class has weaknesses — gaps in its armor. Increased pressure from a united working class can exploit those gaps and secure greater victories. The lesson of the conviction of Amber Guyger then is to struggle, to unite, to persist.