by Carolyn Winslow, Published on Socialist Action, June 11, 2019

America has long lauded its school system as a Great Equalizer—a tool that provides all students, regardless of social standing, with the tools necessary to succeed. Thus, goes the narrative, all differences in outcome can be attributed to individual choices, absolving capitalism and the structures tied to it of their responsibility.

Education has the power to be a tool of liberation, but the truth about America’s schools is that they are typically used for social reproduction—that is, to acculturate young people into the norms of their particular class under capitalism. This reality manifests in a number of ways, including the tendency of schools to punish children of color more harshly than their white peers (feeding the highly profitable school-to-prison pipeline) and serving imperialist ends by teaching students that their cultures are “uncivilized” and their language “unsophisticated.” Even in our allegedly post-imperialist era, these tendencies shine through, albeit in more subtle ways.

One small manifestation of the reality of American schools can be found in the experiences of Alicia Thomas. As of this writing, Thomas is an Ethnic Studies teacher at Holyoke High School in Holyoke, Mass. That may or may not be the case for long—and not because of Thomas’ skills as a teacher. She has two Master’s degrees, and is more highly qualified than the large majority of her peers. Her students have nothing but glowing praise for her, and previous principals and observers have given her high ratings on observations. She relies on critical race theory as the framework of her pedagogy

Further, Thomas fills an important role in her school community as a Black woman. Research has noted that students of color whose teachers are racially and ethnically diverse are more likely to graduate high school, have fewer absences, and are more likely to succeed in college, among other markers of success. Holyoke High School—like the city it’s in—has an 80% Latinx population, and not many teachers of color. Given this, one would think that Thomas would become a star teacher.

Sadly, in the teaching profession, Thomas’ career has followed a pattern.

“Usually, there’s a big welcome when I start at a school,” she says. “I’m highlighted as a teacher of color. Then, I start doing the work, and there’s usually a moment when I get confronted.”

At Holyoke, that moment came when the school’s principal pressured Thomas into enforcing a “no hat” policy. Such a policy has long been common in American public schools, but research has shown it to be consistently enforced in racist manners, and Thomas showed this research to her principal. She has further highlighted:

“I see white kids wearing cowboy hats around school with no consequences,”

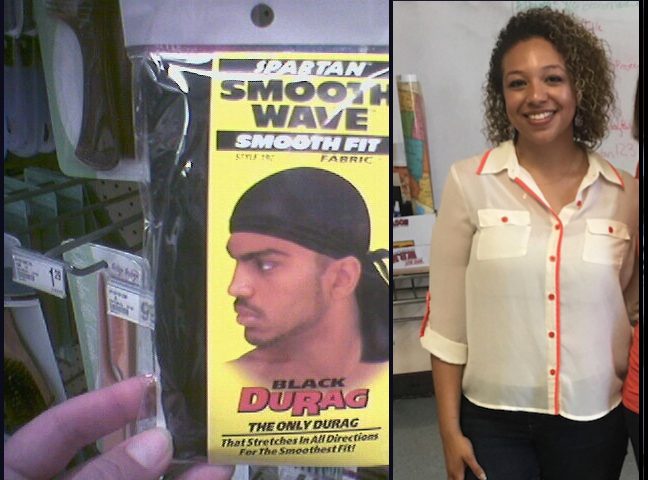

and went on to note that the school policies make no official mention of durags (headwear mostly worn by people of color for haircare purposes), which students have been disciplined over.

When, in response to all of this, Thomas told the principal she was taking a stand, based on research, by refusing to enforce the policy, she received a verbal warning, followed by a written warning.

Thomas views empowering students as an essential element of her job. Marxist educator Paulo Freire wrote that empowered students know they are “transformers of the world,” but that schools teach students they are merely passive observers of the world, incapable of changing its face. That’s not true in Thomas’ classes, where she encourages students to question rules, examine the sources of power, and create change.

Her revolutionary curriculum includes having students create resistance art, write letters to the district superintendent on the importance of a social justice curriculum, and organize meetings with local politicians to discuss important issues on race. In short, she calls on her students to challenge the very institutions they are in, in direct opposition to the typical expectations of a teacher, whose job is primarily to reinforce the system.

The result? Her principal has told her—despite her certainty that he is being dishonest—that he is 99% sure her position will not exist in the coming school year. The school is protecting capitalism, and not its victims, which it allegedly exists to serve.

“I don’t think he consciously knows what he’s doing,” Thomas says of her principal. “He’s just trying to avoid confrontation and make his life easier.”

But, as she notes, making his life easier means playing right into the system of social reproduction in education. Thomas teaches students to buck the trends of social reproduction, and in response, the system attempts to silence her.

Thomas is not alone in her experience. Despite education policy experts’ calling for more teachers of color, the profession is still 80 percent white, and has hovered around that number for years. Numerous narratives similar to Thomas’ exist.

The education needs more Alicia Thomases, but first, it needs the first Alicia Thomas back. Thomas has reached out to local organizers, media, and politicians, but she also encourages anybody reading this to contact the Holyoke Public Schools on her behalf (contact information is on their website) to call for her reinstatement by pointing out the importance of teachers of color.

*Durag photo by Irina Slutsky