by UK Drone Wars, Published on Global Research, June 10, 2019

Lowering the threshold for the use of force

Politicians know that the public do not like to see young men and women sent overseas to fight in wars which often have remote and unclear aims. Potential TV footage of grieving families awaiting funeral corteges has been a definite restraint on political leaders weighing up the option of military intervention. Take away that potential political cost, however, by using unmanned systems, and it makes it much easier – perhaps too easy – for politicians to opt for a quick, short-term ‘fix’ of ‘taking out the bad guys’ rather than engaging in the often difficult and long-term work of solving the root causes of conflicts through diplomatic and political means.

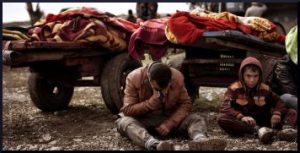

Transferring the risk and cost of war from soldiers to civilians

Keeping ‘our boys’ safe through using remotely-controlled drones to launch air strikes comes at a price. Without ‘boots on the ground’ air strikes are inherently more dangerous for civilians on the ground. Despite claims of the defence industry and advocates of drone warfare, it is simply not possible to know precisely what is happening on the ground from thousands of miles away. While the UK claims, for example, that only one civilian was killed in the thousands of British air and drone strikes in Iraq and Syria, journalist and casualty recording organisations have reported thousands of deaths in Coalition airstrikes.

Keeping ‘our boys’ safe through using remotely-controlled drones to launch air strikes comes at a price. Without ‘boots on the ground’ air strikes are inherently more dangerous for civilians on the ground. Despite claims of the defence industry and advocates of drone warfare, it is simply not possible to know precisely what is happening on the ground from thousands of miles away. While the UK claims, for example, that only one civilian was killed in the thousands of British air and drone strikes in Iraq and Syria, journalist and casualty recording organisations have reported thousands of deaths in Coalition airstrikes.

It is also hard not to connect the awful terrorist attacks that have taken place here in the UK and in Europe to these military interventions. While the public as well as senior military and security officials understand that there is a clear link between military intervention and terror attacks at home, politicians continue to baulk at the connection. The reality though, as Air Marshall Greg Bagwell argued told us

“When you have an asymmetric advantage, enemies seek to find a way around it, and that is what terrorism is. There is a danger that you shift the way an enemy target you and looks for vulnerabilities, and that is where we find ourselves.”

Expanding the use of ‘targeted killing’

Perhaps the most controversial aspect of armed drones has been their use by the United States, Israel and the UK for targeted killing. Legal scholars define targeted killing as the deliberate, premeditated killing of selected individuals by a state who are not in their custody. Where International Humanitarian Law (the Laws of War) applies, targeted killing of combatants may be legal. Outside of IHL situations, International Human Rights Law applies and lethal force may only be used when absolutely necessary to save human life that is in imminent danger. This does not appear to be the case for many of the drone targeted killing that have been carried out, for example, by the US in Pakistan and Yemen.

Perhaps the most controversial aspect of armed drones has been their use by the United States, Israel and the UK for targeted killing. Legal scholars define targeted killing as the deliberate, premeditated killing of selected individuals by a state who are not in their custody. Where International Humanitarian Law (the Laws of War) applies, targeted killing of combatants may be legal. Outside of IHL situations, International Human Rights Law applies and lethal force may only be used when absolutely necessary to save human life that is in imminent danger. This does not appear to be the case for many of the drone targeted killing that have been carried out, for example, by the US in Pakistan and Yemen.

While some argue that it is the policy of targeted killing that is wrong, not the weapon used to carry out it out, it is very difficult to imagine that the wholesale expansion of targeted killing would have occurred without the technology. In the UK, campaigners have long been calling on the government to set out its policy on the use of armed drones outside a situation of armed conflict, something the government has so far refused to do.

Enabling video-game warfare

Separate, but connected to the idea that drones lower the threshold for using lethal forces is the notion, as Philip Alston the former Special Rapporteur on extra judicial killing, put it of the ‘PlayStation mentality’. Alston and others suggest that the vast physical distance between those operating armed drones and the target makes that act of killing much easier. The physical distance induces a kind of psychological ‘distancing’.

There are strong objections to this notion, particular by those involved. Drone pilots, it is argued, are highly trained professionals that are able to distinguish between a video games and real life. Furthermore, it is widely reported that some drone pilots are suffering from post-traumatic stress from having to see the results of their strikes, hardly an indication of detachment. On the other hand, there is some evidence for a ‘PlayStation’ mentality. In 2010 an Afghan convoy of vehicles was hit by an US airstrike involving drones in which 23 civilians were killed. A subsequent USAF investigation found that the Predator crew wanted to attack and “ignored or downplayed” evidence suggesting the convoy was not a hostile target. Elsewhere, in Dr Peter Lee’s recent book, Reaper Force, containing detailed interviews with British RAF Reaper crews, several talked about missions where they became fixated on a target and were ready to strike despite the presence of civilians. Only direct intervention from others meant the strikes did not take place.

There are strong objections to this notion, particular by those involved. Drone pilots, it is argued, are highly trained professionals that are able to distinguish between a video games and real life. Furthermore, it is widely reported that some drone pilots are suffering from post-traumatic stress from having to see the results of their strikes, hardly an indication of detachment. On the other hand, there is some evidence for a ‘PlayStation’ mentality. In 2010 an Afghan convoy of vehicles was hit by an US airstrike involving drones in which 23 civilians were killed. A subsequent USAF investigation found that the Predator crew wanted to attack and “ignored or downplayed” evidence suggesting the convoy was not a hostile target. Elsewhere, in Dr Peter Lee’s recent book, Reaper Force, containing detailed interviews with British RAF Reaper crews, several talked about missions where they became fixated on a target and were ready to strike despite the presence of civilians. Only direct intervention from others meant the strikes did not take place.

Seducing us with the myth of ‘precision’

Drones permit, we are told, pin-point accurate air strikes that kill the target while leaving the innocent untouched. Drone advocates seduce us with the notion that we can achieve control over the chaos of war through technology. The reality is that there is no such thing as a guaranteed accurate airstrike While laser-guided weapons are without doubt much more accurate than they were even 20 or 30 years ago, the myth of guaranteed precision is just that, a myth. Even under test conditions, only 50% of weapons are expected to hit within their ‘circular error of probability’. Once the blast radius of weapons is taken into account and indeed how such systems can be affected by things such as the weather, it is clear that ‘precision’ cannot by any means be assured.

Politicians and defence officials too have been seduced by the myth of precision war and are opening up areas that would previously been out of bounds – due to the presence of civilians – to air strikes. Perhaps most telling, internal military data which counters the prevailing narrative that drones are better than traditional piloted aircraft is simply classified.

Ushering in permanent war

Perhaps the most dangerous aspect of the rise of remote, drone warfare is that it is ushering in a state of permanent/forever war. With no (or very few) troops deployed on the ground and when air strikes can be carried out with impunity by drone operators who then commute home at the end of the day, there is little public or political pressure to bring interventions to an end.

Drones are enabling states to carry out attacks with seemingly little reference to international law norms. US law professor Rosa Brooks argued in a disturbing article in Foreign Policy that ‘there’s no such thing as peacetime’ anymore. “Since 9/11,” she writes “it has become virtually impossible to draw a clear distinction between war and not-war.” Rather than challenging the erosion of the boundaries between crucially distinct legal frameworks, Brooks argues that we must simply accept that “the Forever War is here to stay.” To do otherwise she maintains is “largely a waste of time and energy. “Wartime is the only time we have” she insists.

The slide towards forever war must be rejected and resisted. It is incumbent on us all, citizen, politician, military officer, to work towards global peace and security, not permanent warfare.