Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro (R) alongside OPEC Secretary-General Mohammed Barkindo (L) with Venezuelan Vice-President Delcy Rodriguez and Oil Minister Manuel Quevedo behind. (Presidential Press)

by Paul Dobson, published on Venezuelanalysis, January 9, 2019

Merida, January 9, 2019 (venezuelanalysis.com) – Venezuela has assumed the presidency of the world’s oil-exporting alliance, OPEC, starting this month and lasting for one year.

The position will be occupied by Venezuela’s Oil Minister and President of the State-run oil corporation PDVSA, Manuel Quevedo. OPEC presidents are elected by their conference and are rotational.

The announcement came amidst a visit to Caracas by OPEC Secretary General Mohammed Barkindo to participate in the upcoming swearing in of President Maduro to his new term in office.

¡Saludamos la llegada del Secretario General de la OPEP, Mohammad Barkindo, a la Patria de Bolívar y Chávez!

Revisaremos la agenda de trabajo de Venezuela como presidente de la Conferencia

de la OPEP con el objetivo de lograr la estabilidad del mercado petrolero mundial. pic.twitter.com/Nbe4KA5YiI— Manuel Quevedo (@MQuevedoF) January 8, 2019

“We salute the arrival of OPEC Secretary General Mohammed Barkindo to the nation of Bolivar and Chavez. We will review the work schedule of Venezuela as President of the Conference of OPEC with the objective of achieving the stability of the world oil market,” tweeted Quevedo.

Speaking from Miraflores Palace Tuesday, Barkindo reiterated Venezuela’s commitment to current OPEC policies, and in particular to production cuts which look to keep oil prices stable.

Venezuela “has without a doubt shown its great virtues which helped us come through the recent difficult times which we have seen with the fall in oil prices,” he told reporters.

Oil prices, which hit a four-year high in October 2018, have began to recover from a subsequent slump, closing around $61 a barrel Tuesday. A collapse in prices which started in mid-2014 ─ in part due to US shale oil flooding the market ─ had a significant impact on the national budgets of Venezuela and other oil-dependent nations.

For his part, President Maduro outlined the main policies that Venezuela will promote whilst leading OPEC.

“We have talked of a plan for 2019 to balance, stabilise, and govern the oil market in the best way in alliance with the oil producing nations of OPEC and the non-OPEC countries too,” he explained.

“We had very low, unfair [oil] prices for 36 months and at the end of 2017 and part of 2018. [OPEC] managed to establish balanced prices, this is the objective and we will achieve it with the agreement signed a month ago,” Maduro went on to state.

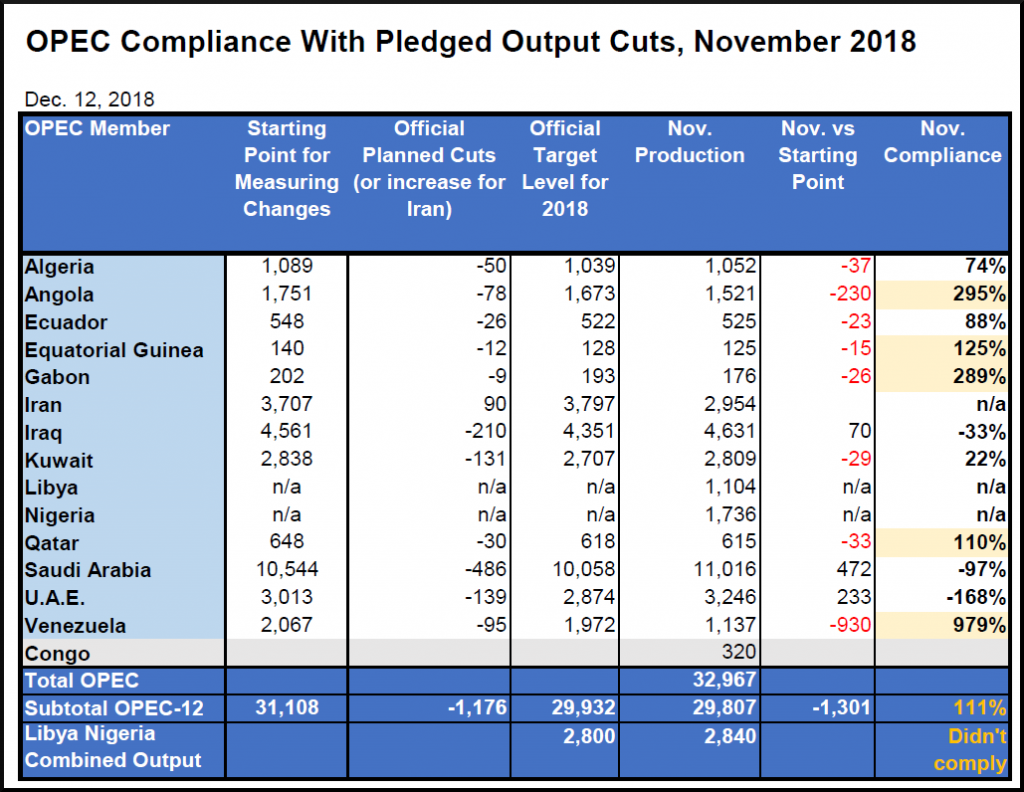

OPEC nations recently agreed to a further 1.2 million barrels per day (bpd) of cuts in Vienna, Austria on December 7. OPEC nations are to reduce production by 800,000 bpd and Russia by 400,000 bpd.

Another issue which Venezuela is due to promote in its new position as OPEC president is to push for oil payments in non-dollar currencies or in cryptocurrencies, such as Venezuela’s oil and mineral-backed Petro. As part of efforts to break dollar hegemony of the oil market, Venezuela now prices its oil in Chinese Yuan.

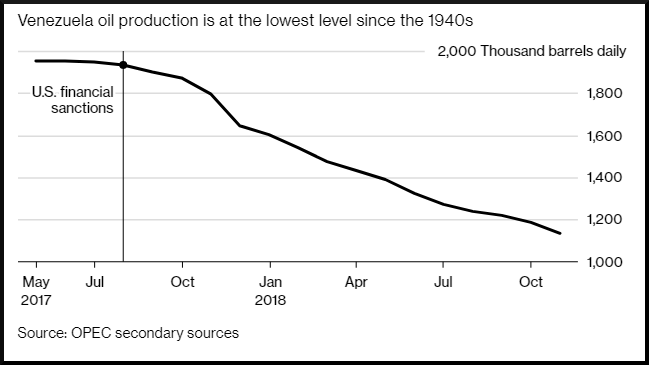

Likewise, Caracas will try to use its OPEC position to counter US-led financial sanctions which block Venezuela’s access to credit, debt restructuring, and other financial dealings, as well as prohibiting the return of over US $1 billion of profits a year from PDVSA’s US subsidiary CITGO. Independent analysts have estimated sanctions as costing the country over US $6 billion in lost oil revenue whilst President Maduro claims that they cost the country more than US $20 billion in general during 2018.

“We reject the sanctions against our country,” Quevedo told press at a recent ministerial meeting of OPEC. “The attack against the economy of an oil producing nation tends to destabilise the world oil market.”

Foreign investment to boost production?

Caracas announced two important deals with foreign oil firms this week in the hope that they will help boost production, which has fallen from 2.5 million bps in 2015 to 1.18 million bpd in November 2018 as a result of a brain drain, sabotage, underinvestment, poor managerial decisions, US sanctions, and corruption.

Foreign investment is an important part of reaching a 2 million bpd target by the end of 2019, Minister Quevedo has claimed. However, some analysts are worried about the secondary effects of such deals on national sovereignty.

Recent reports from the Sinovensa mixed company in the Orinoco Belt, which saw significant Chinese investment in 2018, have already shown fruitful production increases as a result.

This week, French firm Maurel & Prom bought out Royal Dutch Shell’s stake in the Venezuelan mixed firm Petroregional for €70 million (US $80.5 million), which extracts light oil in Maracaibo Lake. It has been announced that with a reported French investment of US $400 million, production is expected to increase from 15,500 bpd to 70,000 bpd. Under the terms of the agreement, PDVSA will conserve 60 percent of the mixed company.

EREPLA deal “unusually favourable to foreign company”

In contrast to the Maurel & Prom contract, it has also been reported that a 25-year deal was signed with unknown US based firm EREPLA in November 2018, which has been described by financial firm Argus as “unusually favourable” to the US company.

Little is known of EREPLA or its board of directors, with Reuters claiming that Harry Sargeant III, magnate and ex-Financial Chairman of the US Republican Party, is one of their owners. The small company, which was only legally registered in the US on November 8, 2018, a mere day before signing the PDVSA deal, has managed to extract a contract from PDVSA which revives a number of practices, previously eliminated in the Chavez-era, of oil so-called service contracts. PDVSA is yet to make any official comment on the deal, and analysts have already expressed concern that the deal violates Venezuela’s 2001 Hydrocarbons Law.

The deal, which is extendable for a further 15 years, is due to bring US $500 million of investment to the Tia Juana, Rosa Mediano fields in Maracaibo Lake and the Ayacucho 5 field in the Orinoco Belt. It assigns 49.9 percent of the new mixed company to EREPLA, and passes 100 percent of the output to the US firm, which is expected to repatriate 50.1 percent of sale profits back to PDVSA.

Day to day running, purchasing, exporting, and the sale of the oil produced is to be completely controlled by EREPLA, except in the case of fulfilling PDVSA’s hefty oil quota to China, which will be agreed upon by both parts.

Whilst EREPLA is due to supply the rigs and crews for the fields, other costs will be split between the two partners, whilst the US firm find themselves exempt from Venezuelan labour laws under the Service Contract clause, as well as from paying its share of the 30 percent oil royalty which PDVSA is due to cover.

“We believe that the new model created in this agreement is in the national interest of the United States,” stated a Harry Sargeant Oil Management Group lawyer who signed the documents on behalf of EREPLA.

An EREPLA statement on the deal describes how it looks to “revitalise” Venezuela’s oil industry. It goes on to explain that new terms and conditions have been applied as previous contracts “fermented corruption and bad management.” EREPLA also argued that the deal will help prevent “US adversaries” such as Chinese and Russian firms from gaining further ground in the oil-rich country.

It is unclear at this point how the new deal will function in light of US financial sanctions against Caracas, as a license from the US Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) is still pending, but the statement assures that the company’s work “will be carried out in accordance with the economic sanctions enforced by the U.S. Treasury Department.”

Oil deals in Venezuela were notoriously favourable to foreign firms until 2001, in terms of profit repatratriation, labour laws, running costs, and local accountability, until Hugo Chavez’ Hydrocarbons Law broke the tradition, ensuring Venezuelan control over joint ventures. Another Chavez decree in 2007 capped foreign participation in oil deals at 40 percent. However, in December 2017 the National Constituent Assembly approved a “Foreign Investment Law” meant to improve conditions for foreign capital investments in Venezuela.