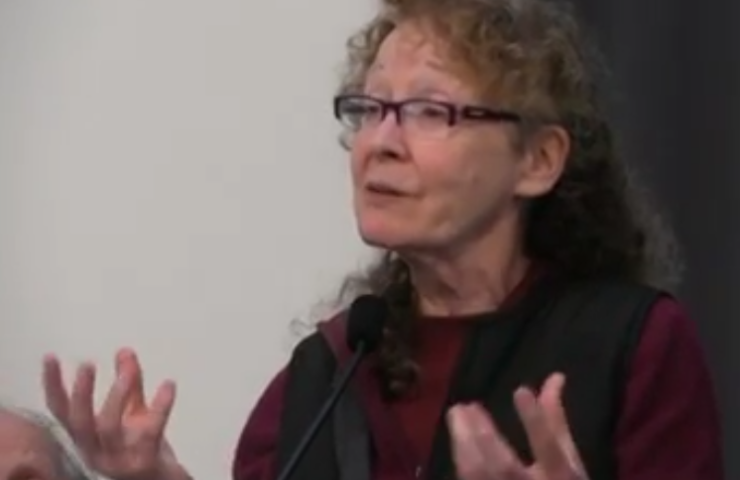

by Kathy Kelly, originally posted on Voices for Creative Nonviolence, Feb 20, 2018

Kathy Kelly, on Feb 15 2018, addressed NY’s “Stony Point Center” outlining the history of peaceful resistance and U.S.-engineered catastrophe in Yemen.

TRANSCRIPT:

So, thank you very much to Erin who apparently had asked the question “What are we going to do about Yemen?” and that was part of what generated our gathering here today; and Susan, thank you so much for inviting me to come and picking me up; to the Stony Point Center people, it’s a privilege to be here with you and certainly, likewise to all who have come, and to be with these colleagues.

I think the urgency of our gathering tonight is indicated by the words that Muhammad bin Salman, the crown prince of Saudi Arabia, spoke on a nationalized, televised speech in Saudi Arabia on May 2nd of 2017 when he said a prolonged war is “in our interest” – regarding the war in Yemen. He said, “Time is on our side” regarding the war in Yemen.

And I see that as particularly urgent because it’s likely that the Crown Prince, Muhammad bin Salman, who is by all accounts the orchestrator of the Saudi-led coalition’s involvement in prolonging the war in Yemen, is going to come to the United States – in Britain they managed to push back his arrival there: there was such a strong movement, led by young Quakers, actually, in the UK – and he probably will come to the United States and most certainly, if that trip happens, to New York, and I think that gives us an opportunity to say to him, and to all of the people focused on him, that time is not on the side of the civilians who suffer desperately; and their situation will be described much further throughout the course of our evening together.

I’ve been asked to speak a bit about the war, the history of the war and the proxy wars and the causes. and, And I want to say most humbly to [] that I know that any child, in the Yemeni marketplace, selling peanuts on the corner, will always know more about the culture and the history of Yemen than I ever can. Something I’ve learned over the years with Voices for Creative Nonviolence is that if we wait till we’re perfect we’ll wait a very long time; so I’ll just job in.

I think one place to start is with the Arab Spring. As it began to unfold in 2011 in Bahrain, at the Pearl Mosque, the Arab Spring was a very very courageous manifestation. Likewise in Yemen, and I mostly want to say that young people in Yemen risked their lives beautifully to raise grievances. Now, what were those grievances that so motivated people to take very valiant stances? Well, they’re all true today and they’re things that people can’t abide with: Under the 33-year dictatorship of Ali Abdullah Saleh, Yemen’s resources were not being distributed and shared in any kind of equitable way with the Yemeni people; there was an elitism, a cronyism if you will; and so problems that should never have been neglected were becoming alarming.

One problem was the lowering of the water table. You don’t address that, and your farmers can’t grow crops, and the pastoralists can’t herd their flocks, and so people were becoming desperate; and desperate people were going to the cities and the cities were becoming swamped with people, many more people than they could accommodate, in terms of sewage and sanitation and healthcare and schooling.

And also, In Yemen there were cutbacks on fuel subsidies, and this meant that people couldn’t transport goods; and so the economy was reeling from that, the unemployment was going higher and higher, and young university students realized, “There’s no job for me when I graduate,” and so they banded together.

But these young people were remarkable also because they recognized the need to make common cause not just with the academics and the artists who were centered in, say, Ta’iz, or with the very vigorous organizations in Sana’a, but they reached out to the ranchers: men, for instance, who never left their house without carrying their rifle; and they persuaded them to leave the guns at home and to come out and engage in nonviolent manifestations even after plainclothesmen on rooftops shot at the place called “Change Square” that that they had set up in Sana’a, and killed fifty people.

The discipline these young people maintained was remarkable: they organized a 200 kilometer walk walking side by side with the ranchers, and the peasantry, the common people, and they went from Ta’iz to Sana’a. Some of their colleagues had been placed in terrible prisons, and they did a lengthy fast outside the prison.

I mean, It’s almost as if they had Gene Sharp’s, you know, table of contents, and were going through the nonviolent methods they could use. And they were also just spot-on about the main problems that Yemen was facing. They should have been given a voice: They should have been included in any negotiations; people should have blessed their presence.

They were sidelined, they were ignored, and then civil war broke out and the means that these young people tried to use became all the more dangerous.

And I want to comment that, at this point in Southern Yemen, The United Arab Emirates, part of the Saudi-led coalition, are running eighteen clandestine prisons. Among the methods of torture, documented by Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, is one in which a person’s body is trussed to a spit that rotates over an open fire.

So when I ask myself “Well, what happened to those young people?” Well, when you’re facing possible torture, imprisonment from multiple groups, when chaos breaks out, when it becomes so so dangerous to speak up, I know that I for my safety and security have to be very careful about asking “well where is that movement?”

And once you go back to the history of Ali Abdullah Saleh: Because of some very skilled diplomats, and because of the Gulf Cooperation Council which was – various countries represented this council on the Saudi peninsula, and because people by and large who were part of these elites didn’t want to lose their power, Saleh was edged out. A very skillful diplomat – his name was Al Ariani – was one of the people who managed to get people to come to a negotiating table.

But these students, the Arab Spring representatives, the people representing these various grievances, were not included.

And so as Saleh more or less went out the door after his 33- year dictatorship he said, “Well, I will appoint my successor:” and he appointed Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi. Hadi is now the internationally recognized president of Yemen; but he’s not the elected president, there was never an election: he was appointed.

At some point after Saleh had left, there was an attack on his compound; some of his bodyguards were wounded and killed. He himself was wounded and it took him months to recover; and he decided “that’s it.” He decided to make a compact with people he had formerly persecuted and fought against, who were amongst the group called the Houthi rebels. And they were well equipped, they marched into Sana’a, took it over. The internationally recognized president, Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi, fled: he is still living in Riadh, and that’s why we talk about a “proxy war” now.

The civil war continued, but in March of 2015, Saudi Arabia decided, “Well, we’ll enter into that war and represent Hadi’s governance.” And when they came in, they came in with a full cache of weaponry, and under the Obama administration, they were sold (and Boeing, Raytheon, these major corporations love to sell weapons to the Saudis because they pay cash on the barrelhead), they were sold four combat littoral ships: “littoral” meaning they can go along the side of a coastline. And the blockades went into effect which greatly contributed towards starvation, toward an inability to distribute desperately needed goods.

They were sold the Patriot missile system; they were sold laser-guided missiles, and then, very importantly, the United States said “Yes, when your jets go up to do the bombing sorties” – that will be described by my colleagues here – “we will refuel them. They can go over, bomb Yemen, come back into Saudi airspace, the U.S. jets will go up, refuel them in midair” – we can talk more about that – “and then you can go back and bomb some more.” Iona Craig, a very respected journalist from Yemen has said that if the mid-air refueling stopped, the war would end tomorrow.

So the Obama Administration was very very supportive; but at one point 149 people had gathered for a funeral; it was a funeral for a very well-known governor in Yemen and the double-tap was done; the Saudis first bombed the funeral and then when people came to do rescue work, to do relief, a second bombing. And the Obama administration said, “That’s it – we can’t guarantee that you’re not committing war crimes when you hit these targets” – well, by then they had already bombed four Doctors Without Borders hospitals. Keep in mind the United States had bombed a Doctors Without Borders hospital October 2nd, 2015. October 27th, the Saudis did it.

Ban-Ki-Moon tried to say to the Saudi Brigadier-General Asseri that you can’t go around bombing hospitals, and the General said “Well, we’ll ask our American colleagues for better advice about targeting.”

So think about the green-lighting that Guantanamo creates when the United Arab Emirates has a network of eighteen clandestine prisons. Think about the green-lighting that our bombing of a Medecins Sans Frontieres (Doctors Without Borders) hospital creates, and then the Saudis do it. We have played an enormous role, we as United States people whose governance has been involved steadily in the civil war and the Saudi-led-coalition war.

We can call that a proxy war because of the involvement of nine different countries, including Sudan. How is Sudan involved? Mercenaries. Feared Janjaweed mercenaries are hired by the Saudis to fight on up the coast. So when the Crown Prince says “Time is on our side,” he knows that those mercenaries are taking small town after small town after small town, getting close to the vital port of Hodeidah. He knows that they have got loads of weapons and more coming, because our President Trump, when he went over to dance with the princes, promised that the spigot is back on and that the United States will again sell weapons.

I want to close by mentioning that when, a little over a year ago, President Trump gave an address to both houses of Congress, he lamented the death of a Navy Seal, and the Navy Seal’s widow was in the audience – she was trying to maintain her composure, she was crying bitterly, and he shouted over the applause that went on for four minutes as all the senators and all the congressmen gave this woman a standing ovation, it was a very strange event; and President Trump was shouting “You know he’ll never be forgotten; You know he’s up there looking down on you.”

Well, I began to wonder, “Well, where was he killed?” And nobody ever said, during the whole of that evening’s presentation, that Chief Petty Officer “Ryan” Owens was killed in Yemen, and that same night, in a village, a remote agricultural village of Al-Ghayil, Navy Seals who had undertaken an operation suddenly realized “we’re in the middle of a botched operation.” The neighboring tribespeople came with guns and they disabled the helicopter that the Navy Seals had landed in, and a gun battle broke out; the Navy Seals called in air support, and that same night, six mothers were killed; and ten children under age thirteen were among the 26 killed.

A young 30-year-old mother – her name was Fatim – had not known what to do when a missile tore through her house; and so she grabbed one infant in her arm and she took the hand of her five year old son and she started shepherding the twelve children in that house, that had just been torn apart, outside; because she thought that was the thing to do. And then who knows, maybe, you know, the heat sensors picked up her presence emerging out of the building. She was killed by a bullet at the back of her head: her son described exactly what happened.

Because, I think, of American exceptionalism, we only know of one person that – and we don’t even know where he was killed, on that night.

And so to overcome that exceptionalism – to reach out the hand of friendship – to say that we do not believe time is on the side of any child at risk of starvation and disease, and their families, who simply want to live;

Time is not on their side.

Thank you.